Sorry, couldn't resist

Hedy Lamarr: Actress, Movie Star, Weapons Designer

The arms dealer was Fritz Mandl, an Austrian military arms merchant and munitions manufacturer, a tycoon with numerous unsavory customers in pre-World War II Europe. By “unsavory customers” I mean, for example, Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler.

The starlet was Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler. As a young actress, she married Mandl. Understandably, not soon after, she seized an opportunity to escape from him (disguising herself as her maid) and fled to England, and then to America, settling in Hollywood.

She changed her name to Hedy Lamarr and movie mogul Louis B. Mayer promoted her as “the world's most beautiful woman.” She became a bona fide movie star. Among her many roles, she played Delilah in Cecil B. DeMille's “Samson and Delilah,” the third highest-grossing film ever at the time of its release and recipient of two Oscars. But, Ms. Lamarr found movie making to be boring. In her spare time, she took up inventing.

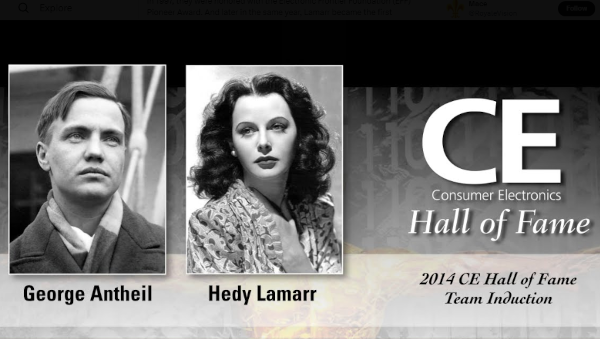

The composer was George Antheil. During piano performances, “the bad boy of music” was noted for hitting the piano rather than playing it and often injured himself when doing so. Also, he would sometimes walk out on stage and lay a revolver on the piano. In most concert halls, this is generally frowned upon.

Alert readers will recall that Antheil wrote the score for the Ballet Mécanique, a topic discussed in my last blog. The Ballet Mécanique was an experimental film in the Dadaist post-Cubist style. Among other instruments, Antheil's score calls for 16 synchronized player pianos used in a novel “note hopping” manner. He spent a good deal of effort trying to get the player pianos synchronized, devising various ways to achieve that.

The year is 1941. War rages on land, and on the sea. The race is on to develop newer and better weapons. Naval weapons designers are searching for a reliable way to guide torpedoes as they speed toward their targets. Radio guidance seems like the answer, but an adversary can easily broadcast a jamming signal on the guiding frequency and send the torpedo off course. A solution is urgently needed.

Ever inquisitive, and anxious to help her adopted country, Ms. Lamarr seized upon the problem of the vulnerability of torpedo radio guidance. To overcome jamming countermeasures, she proposed that a torpedo's guidance signal could use “frequency hopping,” a technique where the carrier signal is switched between different frequencies. A brilliant solution, but there was a problem. If the frequency linking the transmitter to the receiver is changing, how do those changes stay synchronized? Without that, communication is lost.

Ms. Lamarr knew that a friend of hers, the eccentric George Antheil, had devised ways to synchronize player pianos. She enlisted his aid, and together they invented the novel solution of using piano rolls to control the switching between 88 carrier frequencies (you will note that a piano has 88 keys). Piano rolls, one copy in the transmitter and an identical roll in the torpedo, playing simultaneously, would contain a record of the frequency hops, thus maintaining synchronization.

The result of their work was U.S. patent 2,292,387, titled “Secret Communication System,” granted on August 11, 1942. Its precis states, “This invention relates broadly to secret communication systems involving the use of carrier waves of different frequencies, and is especially useful in the remote control of dirigible craft, such as torpedoes. An object of the invention is to provide a method of secret communication which is relatively simple and reliable in operation, but at the same time is difficult to discover or decipher.” The patent is filed under Ms. Lamarr's then-legal name, Hedy Kiesler Markey; Antheil is the co-inventor.

After consideration, the wartime U.S. Navy rejected their invention, but the idea resurfaced in the 50's and 60's when more practical implementations became available. In 1997, Hedy Lamarr and (posthumously) George Antheil received the Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award for their achievements in wireless communication technology. Both were also posthumously inducted into the CE Hall of Fame in 2014 for their pioneering work. Today, spread-spectrum techniques are widely used in communications systems.

Neither Lamarr nor Antheil received any financial benefit from their work.

- Log in or register to post comments

This is 1874! You'll be able to sue HER!

I forgot about this. Read it and found it hard to believe many years back, but found out it was true. Amazing that a Hollywood starlet would come up with something so profoundly important in the field of secure and robust radio communication. A technology one could say changed the world. If I'm correct it is still used 'till this very day. Kind of like if Fabio invented the blue LED...LOL! We can thank Shuji Nakamura for giving us the blues. To my knowledge he neither made a blockbuster movie or hawked margarine, but I digress. Ken, keep the interesting stories coming. I always read your blog as it entertains and enlightens.