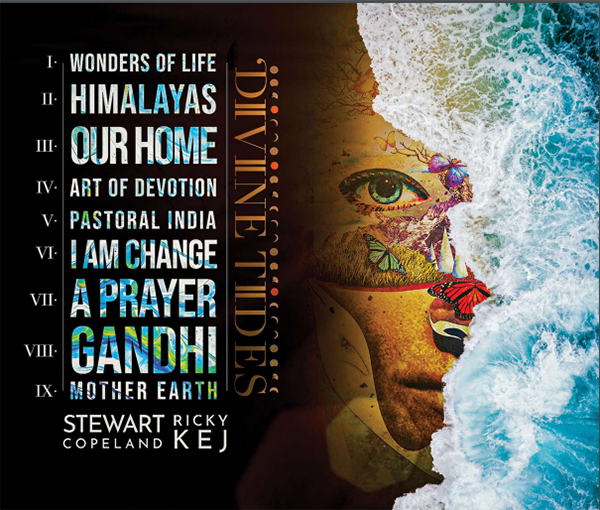

The Divine Secrets Behind Mixing Stewart Copeland and Ricky Kej’s Grammy-Winning Best Immersive Audio Album Divine Tides in 360 Reality Audio

It’s no surprise, really, that Stewart Copeland and Ricky Kej’s collaborative effort Divine Tides won a Grammy Award in February 2023 for Best Immersive Audio Album. Interestingly, in 2022, Divine Tides won its first Grammy for Best New Age Album (albeit in its stereo version)—but delve into the rich musical bed of its subsequent Grammy-winning 360 Reality Audio mix somewhat further, and you’ll find an ever-expanding aural tapestry more akin to being world music with its many ethereal under/overtones unfurling all around you.

For their part, Copeland (seen above, and best known as being the innovative drummer for The Police) and Kej (a world-renowned Bangalore, India-based keyboardist/composer) fused their musical vision together to create 33-plus minutes of pure divine bliss. Frankly, the music that comprises Divine Tides is too expansive to be contained in “just” the stereo field—and that’s where the ace surround-sound mixing team of producer Herbert Waltl and mixer Eric Schilling came into the picture to help extend Divine Tides into the Grammy-winning 360 Reality Audio palette where it belongs. (You should be able to find the 360RA mix of on most major surround-enabling streaming platforms.)

“We were actually in contact with them from the very beginning. We talked about this mix early on with them during the initial recording process,” explains Waltl about the collaborative process he and Schilling shared with both Copeland and Kej, “and Eric and I gave them some tips about what we would need in terms of what the ideal stem layout would be, what the ideal tracks for us would be, and how we would separate certain things that would need to be available to us. We wanted to offer the maximum immersive possibilities for working with the elements they gave us.”

Both Copeland and Kej (shown above) were beyond pleased with what they heard of the duo’s 360RA mix—Kej, after listening to a headphone mix of it while he was in India, and Copeland vetting what he heard in person after coming down to the studio—the ultimate result being, both artists had limited critical feedback to share with their two immersive mixmasters. “We had free rein in terms of what we thought was going to work in immersive,” confirms Schilling. Adds Waltl, “Yes, we did have free rein—and that was the beauty of it!” (In other words, no divine artist intervention was required.)

Recently, Waltl, Schilling, and I all got on a Google Meet together to discuss the key differences between stereo mixes and immersive mixes, how to best tap into emotional responses in a spatial audio setting, and how they strive for their mixes to get you to experience hearing certain mix elements well above and well below your ear height.

Mike Mettler: Before we get into the 360 Reality Audio mix of Divine Tides, tell me about your respective immersive audio mixing styles.

Eric Schilling: The way we work is, especially if a release has been out in stereo—and this is a particular philosophy of mine—unless an artist says they really want a remix, our goal is to give them the immersive experience but still maintain the balance of the creative choices they made for the stereo. So, I find the 3D, as I call it, to be a lot more fun to hear because—as a person who’s mixed in stereo my whole career until a couple of years ago—it can be really challenging to get this stuff into a stereo field. Getting it in this 3D field, you just have the chance to hear things you’re not going to hear otherwise—but you can still maintain the balance of the way the artist wanted them to be.

Herbert Waltl: I also want to say something about the differences between stereo and immersive. Although you do want to be authentic to the artist—especially if it’s a “legendary” track, or an older kind of work that is famous—it’s a song the fans, and everybody else, expect to get the same feeling from again, right? You cannot make something like that sound completely different. If it’s a certain piece they’ve known for 20, 30, or 40 years, they want to have the same emotional feeling. They want to feel “at home” with it. They want to, you know, crawl into it. So when we do it the immersive way, you cannot completely deny that feeling. There has to be a connection to that original feeling.

But, on the other hand, and especially with an album like Divine Tides, you don’t want to just “expand” the stereo. That’s just boring! You should really come up with a new listening experience without neglecting the original idea of the artist—because at the end of the day, technology serves the art. The art does not serve the technology.

What the technology can offer is to always be guided by the artist or the musician’s visions. So, we both were very careful not to step on them [i.e., Ricky and Stewart] here. We had them involved, and we tried to feel out what they really meant with this music—the voice leading, how the voices were composed, how they arranged it all, and what the harmonics were doing.

Mettler: Let’s now get into Divine Tides. Were you guys given all the stems to work with for the 360RA mix? What materials were you given the mixing keys to, so to speak?

Schilling: It was mainly stems. I think we might have had a couple of separate tracks, but in this case, it’s mainly stems—but they were pretty extensive stems, so we had a fair amount of control over them. As in, the voices were separate, strings were separate, small percussion was separate, and drums were separate. So, Herbert, I can’t quite remember, but I think we had 18 to 20 stems per song, is that right?

Waltl: I believe it was even more than that, Eric—and that meant we always had options. If there was a stem of a certain section in a song we’d like to pull apart even further, we’d get back to Ricky and say, “Hey, send us more for this section of that song so we can do even more with it.” And that could be a massive ask at times, because we always try to get the stems to help with the workflow, since we’re thinking about the amount of time it would take if we had to start from scratch.

Additionally, we also asked for the multitracks so that Eric had the opportunity to get into even more of the details. That’s worked out for us with all kinds of different projects.

Mettler: Did you follow the running order of the nine tracks on Divine Tides when you started mixing in 360, or was there something you both started on first where you both agreed, “Okay, now we’re on the right track”?

Schilling: My memory is we didn’t really follow the running order. What I always like to do when I mix in 360—and Herbert likes to work this way as well—is I don’t want to start with the most complex song, and I don’t want to start with a simple song. I want to start with a “medium” type of song to establish how we feel about it, and how we’re going to do it. As we get more comfortable with the content, then we get into the more involved songs, and that’s the way we did this one. I seem to think we did “Himalayas” first, but I’m not sure.

Waltl: Me either, but we didn’t even look at the order of the album when we worked on it. As Eric has described, the complexity is important, and to find something first that can establish a good foundation for the album is key. Because at the end, it is an album, so you want some connectivity and some relationships between the songs in the way you come up with your spatial concept. It’s not about stuff “popping” all over the place—but if there’s something there like a story to tell and it continues in another song, then you’ve found a relationship for this mix.

Mettler: I get that. Obviously, in some tracks here, you’re dealing with the orchestral elements, which can be comprised of a lot of tracks just on their own. Did you find those tracks to be a little more difficult to deal with because of the amount of information involved?

Schilling: I wouldn’t say so. Herbert, I don’t know how you felt about it, but at least for me, I didn’t,

Waltl: We always appreciate the idea of the more information we can get, the better. We’re not shying away from that. (chuckles) That also means it takes a lot of time to do it, but we can also go into much more detail. Not just in placement, but in the detail in the mix. And when it comes to Eric and what he does with different reverbs and with delays, that gives us much more options. We never have a problem with anything being “too much.”

Schilling: What we both liked about Divine Tides—and this world music genre specifically—is because this music was so layered, this is the kind of stuff that really works great in immersive. So, I agree with Herbert. I’ve done a couple of things where I only have elements like a piano, a voice, and maybe a bass and a guitar—and that’s actually much harder to do, because there’s just not much content to really grab onto. Having this kind of world-music blend to work with, I thought the immersive format really served it to create an environment for it to live within.

Mettler: Environment is a good word for it, I think. In the case of the kind of music we hear on Divine Tides, you’re literally trying to expand our minds on up into the clouds, aren’t you?

Schilling: (laughs) Yes! And I would tell you that with Herbert, whenever we work together, he kind of thinks that way too. He’ll encourage me by going, “What about if we take this part and put it way up top because it’s more ethereal?”

Mettler: Okay—with that in mind then, I have to ask you, Herbert, what is the most ethereal track on Divine Tides from your point of view, the one you feel takes us above the ceiling, literally?

Waltl: Well. . . (slight pause) I cannot really answer this question! (laugh) Our approach is, we’re really listening to the music to see what the voices do, what the instruments do, and how the arrangement is done. For example, something that one violin plays first may have something else answer it. With that answer, we may be thinking about, “Do we want to put those music elements close together because the answer responds instantly?” Or we’ll go, “Maybe we want to pull it apart because it gives it a more theatrical approach.”

And it’s completely okay to do that if there’s a conversation between the instruments— because it’s more polyphonic-thinking than harmonic. Each song has its own rules as to how it’s written. We don’t have one template. Maybe we start out with a kind of template just to get us started—but then, we really digest the music, and analyze the music to see how well it makes more sense musically and how we can get the biggest impact emotionally in terms of how the music can sound when you’re doing it spatially, and not just in terms of how much movement we can get out of it. It’s really dictated always by the music, and by the composition itself.

Mettler: I feel a track like “Gandhi”—because you have the acoustic guitar figure that opens it up, and then the breadth of the song fills in the space after it—is a good example of how you’re using a wider dynamic range here.

Schilling: That makes sense, yes.

Waltl: And you get those sound effects in those sound clouds, with the synthesizer. Eric actually doubles that up into more than one track.

And then, some of the tracks will be put on the very top, and at the very top. It’s moving—but it’s moving so little that you hardly notice it. You only really notice if you’re listening for it—but it is moving, so it creates a space and a movement, because the music is moving, and the sound is moving. It’s never static in your corner. It is moving, and that creates access to overall spatial realization of the room you are in.

We spend a lot of time on this just to create a spatial realization of what space the music is in, how the music reacts, and what it does next. And then, of course, the same track. or the same sound, is eventually somewhere locally fixed so that it’s not a crazy circus that moves all around you. The music has a point to it, but you still experience the whole space. You are “in it.” That’s a technique we worked a lot of time on, with the delays—putting up the delays, and changing delays to the pitch. Eric, you can maybe explain this a lot better.

Schilling: A lot of times, what we’re trying to do is, if you put a movement in that’s kind of subtle, it just makes the space feel like it expands. Essentially, it’s what you would do if you use a reverb, or use effects. You don’t always need to specifically hear them as being predominant, but they just create a sense of space that we’ve found—especially in 360—between our use of floor[standing] speakers and then going to the height [channels], it would create an incredible 3D space from the floor up to the ceiling. And that’s what we like about 360 a lot—the use of the floor speakers. And as Herbert will explain, you can feel the floor speakers when wearing headphones and where they come in at your throat, almost. They feel below where your ears are.

Waltl: Yes. It can be described as if you’re in this sphere—in a real ball of sound—and that doesn’t have to stop at the height of the ear, if you consider the ear to be the north hemisphere of the globe. It can go down to the south hemisphere—all the way down below your head, and down to your throat.

Even when you hear music “below” your ears, your emotional reaction to it is the same way like it would be in the higher field of your head. I’ve noticed this with other people who have not heard a lot of immersive sounds before. When they put on headphones, it takes a while to really realize what’s going on. It even happens to me sometimes! (laughs) It takes a while, obviously, for your emotions and your sensitivities to kick into this new sphere—this new listening experience.

But if you have what I call “the length axis” as being longer and going down past your head, it is much easier actually to find yourself in that space. As a rudimentary example, if you walk in the jungle and there’s a snake on the ground, you won’t know exactly where the snake is, but you know from where the sound you hear is that it’s down there somewhere! (laughs) Maybe I would know it a little bit better for where a bird was coming at me from above if it wanted to pick my eye out. (more laughter)

Mettler: That is a really good point, because I tend to feel music is more like a full-body experience since it really does appear all around you—not just at your ear height. Just like you said, Herbert, it can be above your head, and below your neck—even all the way to the ground at times.

Waltl: Yes. Music, by itself, is beautiful. It doesn’t need pictures. You can imagine it. You can picture where the music is, and what the sound is telling you about it in whatever way it works in terms of the storytelling or in the more abstract aspects from what you get with different compositions. And that combination of storytelling with a purpose and those more abstract elements makes this Divine Tides album so wonderful to place in an immersive environment like this one.