Old Family Recipe

Stewart is a closely held family company, started in 1947 by Roy Stewart and his sons Marshall, Clifford, Lamar, and Patrick to serve the burgeoning Hollywood film industry. Roy's grandsons Don, Tom, and Grant now run the company, which supplies front- and rear-projection screens for home and commercial theaters, screening rooms, scoring stages, live-broadcast and news sets, events like the Oscars, amusement parks, command-and-control centers, and flight simulators.

The company headquarters in Torrance, California, have expanded over the years to cover five acres with 20 buildings that seem to have sprung up organically. A combination of inside and outside areas are connected by narrow, semi-covered walkways that feel like rabbit warrens.

The tour began in the mixing room, where the precursor ingredients of acetone, solvent, and a vinyl-microsphere powder are blended in a secret recipe to form the solution that will become filmscreens. Most of us started to feel a bit lightheaded in this room, which was permeated with a strong chemical odor. Fortunately, Stewart has implemented state-of-the-art environmental measures to protect its workers and the surrounding neighborhood from any toxic effects.

Screens are first formed by an automatic process in which a huge XY plotter sprays the solution onto the ceiling of large roomsthe largest is 40x90 feet, which defines the biggest seamless screen the company can make. Multiple layers are required, including a mold layer, the body of the screen, and the final optical coating. After the material hardens, it is peeled from the ceiling and prepared to become a projection screen.

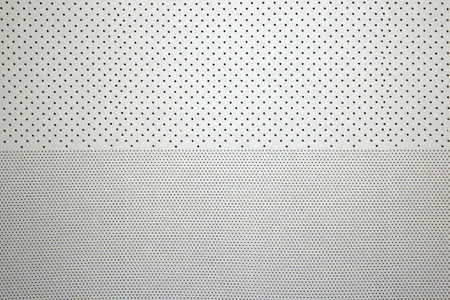

If a screen is to be perforated, it is laid flat on the floor of a very hot room for five days to cure the plastic so it won't deform when it's stuck with thousands of tiny pins. Stewart has designed and built its own perforation machines to assure a high degree of uniformity in the size and spacing of the holes. In commercial-cinema screens, there are 5800 holes per square foot, each measuring 0.045 inch, which means they occupy 8.5 percent of the screen area.

By contrast, home-theater "microperf" screens have 30,000 holes per square foot, and each is only 0.024 inch in diameter, so they occupy 10.2 percent of the screen's area. These holes can cause strange interference patterns when used with digital projectors due to the relationship between the holes and pixels, so Stewart rotates or "skews" the perf pattern by different angles depending on the projector and screen size in order to minimize these artifacts.

Except for the automated spraying process, all Stewart screens are made by hand and checked for quality several times before they are shipped out. Motorized retractable screens are hung in their extended position for a day prior to a final check of the screen and mechanism.

In addition to flat screens, Stewart makes all sorts of projection surfaces, including spheres, shown here before they have a special coating applied to their inner surface. For example, we saw a rotating image of the Earth projected onto one of these spheres, which is a remarkable effect.

Less challenging but more useful in a home theater is the CineCurve screen, which emulates the curvature of a commercial screen and addresses the geometric distortions that occur with the anamorphic projection of 2.35:1 movies. Stewart's most popular home-theater modeleven at a typical price of around $20,000the CineCurve is hand-assembled in what the company calls the Exotics room. Also built in this room is the top-of-the-line Director's Choice screen with full motorized masking, which can be ordered up to 25 feet wide at a cost of up to $125,000.

New at CEDIA this year will be a 2.0:1 Director's Choice and a CineCurve with a slimmer frame. Also at the show will be a new entry-level material called Luxus Studio 1.

Another CEDIA introduction is called AcoustiShade, a window treatment designed to keep external light and sound out and the movie sound in the room. This ingenious system has three layersa sound-attenuating blackout layer called Resonance Controlling Film (RCF), a perforated decorative layer, and an air gap between them that is maintained by magnetic strips in the frame tracks and edges of the RCF layer.

For me, the most important announcement during our visit was a new StudioTek screen—StudioTek 100, a unity-gain material designed to provide almost perfect lambertian diffusion with the same light output in just about any direction. This image-neutral screen is said to exhibit only 3-percent variation in peak-white uniformity from the center to any corner, which is heretofore unheard of. As you might expect, such a screen requires a dedicated, black room with complete control of ambient light because of its wide reflective angle, so Stewart plans to market this material very carefully. However, it provides a highly accurate representation of what the projector is doing, which is why I hope to get one for Grayscale Studio, the video-testing facility for Ultimate AV and Home Theater.

One more interesting introduction was StudioGray 60, a neutral-density gray screen with a gain of 0.6. This should help in rooms with unavoidable ambient light and improve the black performance of very bright projectors. Interestingly, Stewart's gray screens outsell white ones in the home market by a factor of 10:1.

All in all, it was a fascinating day at Stewart HQ. Clearly, the Stewart family has its collective finger on the pulse of the home- and commercial-cinema markets, offering a wide variety of screen materials to suit many different applications. If only they would divulge their carefully guarded vinyl recipeI got a pretty good buzz from the fumes!

If you have an audio/video question for me, please send it to scott.wilkinson@sorc.com.