Is There Sound on Mars?

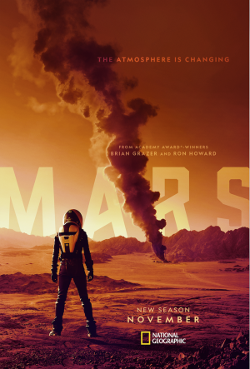

The show’s second season is comprised of a six-episode arc that parallels Season 1’s hybrid format of alternating scripted and documentary sequences predicting what life will be like on the Red Planet after we land there and set up shop, and whether we can leave behind the mistakes we’ve made on Earth or continue to repeat the cycle. To my eyes and ears, MARS was visually stunning and sonically appealing from the get-go, thanks in no small part to the Herculean efforts of Skywalker Sound and the enveloping all-channel score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis that also shine on the subsequently released Season 1 Blu-ray.

In Season 2, we find different factions drawing a line in the red sand, so to speak. “There may be boundaries,” allows Jeff Hephner, who plays the commander of the Lukrum Mining Colony, “but there’s nothing that says they can’t be changed or moved. It takes two to recognize where that line is.” Adds Jihae, who embodies the dual role of a mission commander of Olympus Town on Mars and her former Foundation secretary general twin back on Earth, “There are also boundaries in relation to the planet itself that are very unpredictable. You just don’t know what the planet can do to you.” Concludes Evan Hall, who portrays an operations supervisor for the Lukrum Mining Colony, “This is a very difficult place to live in, but Season 2 shows how it will bring out the very best in humanity — and the worst. That’s the drama of it.”

In Season 2, we find different factions drawing a line in the red sand, so to speak. “There may be boundaries,” allows Jeff Hephner, who plays the commander of the Lukrum Mining Colony, “but there’s nothing that says they can’t be changed or moved. It takes two to recognize where that line is.” Adds Jihae, who embodies the dual role of a mission commander of Olympus Town on Mars and her former Foundation secretary general twin back on Earth, “There are also boundaries in relation to the planet itself that are very unpredictable. You just don’t know what the planet can do to you.” Concludes Evan Hall, who portrays an operations supervisor for the Lukrum Mining Colony, “This is a very difficult place to live in, but Season 2 shows how it will bring out the very best in humanity — and the worst. That’s the drama of it.”

Behind closed doors at an invite-only press roundtable during October’s New York Comic Con at the Javits Center, I asked nine members of the MARS creative team about the aural choices they had to make about scoring the show, the science of sound in space, and whether they’d sign up for a mission to Mars themselves.

Mike Mettler: Do you feel Season 2 has a darker tone than Season 1 did?

Justin Wilkes (MARS co-creator and executive producer, Imagine Entertainment): Well, it’s more complicated — how about that? Season 1 was all about humans versus the planet, and the darkness came from the circumstances the humans were putting the planet through. But now, in a way, it’s darker and more complex because it’s humans versus humans. There are a lot more layers to all the different points of view.

Dee Johnson (Season 2 showrunner and executive producer): That’s a pretty good assessment. Season 1 was dark, but Season 2 is much darker. We also wanted to explore how the people who live there and work there have progressed. There remains a proper amount of fear and respect about the planet, but then the issue becomes more about how people live in a confined space where you never get fresh air.

Wilkes: Now it’s a functioning colony. The issues they faced in Season 1 — Where are we going to go? How are we going to get water? How are we going to set up the habitat? — all of that has been solved, relatively speaking. Now, it’s much more about running the day-to-day business of being on Mars — there are about 200 people in the colony itself at this point, and then there’s the science the Olympus Town colony is performing. It’s also a reflection of our own planet and the challenges we’re facing politically and environmentally, but also how human nature translates to a nascent planet, and how human nature tends to repeat itself over time.

For future seasons, the storytelling is practically endless. And I like looking in the past as a clue to the future. What happens to the generations of people who are born on Mars? They’re now Martians, so now you’ve got Martians versus Earthlings, and who’s controlling who? And why do you have Earth governing Mars? Is there a Martian Tea Party at some point?

Johnson: Martian adolescents — that’s a horrifying thought, actually. (all laugh)

Mettler: What kinds of decisions did you have to make in terms of the show’s overall sound design for both broadcast and for Blu-ray release, in relation to how sound travels in space and within the atmosphere on Mars?

Johnson: The reality of it is not what you want to hear when you’re doing a TV show. (laughs) The science of it is always a dance in terms of wanting it to be as authentic as possible — and yet, we’re still doing a TV show. For instance, you can’t really deal with the gravity in a purely scientific way, because without having massive amounts of money, it would be impossible to film all the weightlessness scenes that would be occurring.

As for the sounds, yeah, there were all kinds of issues discussed: Would they be able to hear that? Would they even be able to make that sound? And there’s no whistling, either.

Mettler: Can you also tell me about the theme music for the show that was composed by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis?

Wilkes: We brought them on in Season 1. They wrote the theme song [“Mars Theme”] and scored the show last season. This season, we used their theme song, but we brought in a really talented composer, Brian Reitzell, someone whom [looks at Johnson] you’ve worked with before.

Johnson: (nods) Brian takes what was done in the first season and embellishes it even more. [Reitzell had previously worked with Johnson on the 2011-12 Starz political-drama series, Boss.]

Wilkes: For the sound design, we worked with the folks at Skywalker Sound, who, as you know, are all fantastic. I think it was fun for those guys because, while there are the environmental aspects of the sound, you’re also living inside of this tin can that feels like a submarine in a lot of ways. Olympus Town and Lukrum Mining Colony have their own distinct sound designs, based on the operations of people’s lungs and their breathing within the soundscape you have in a completely manufactured environment.

Dr. Stephen Petranek (scientific advisor, co-executive producer, and MARS Big Thinker; award-winning author of 2015’s How We’ll Live on Mars, upon which the series is based): Humans will be a lot more careful on Mars than they have been on Earth, and in a much more controlled environment. It’s a mix of human nature where one part is motivated by capital return, and the other part is motivated by doing the right thing. The questions we faced for Season 2 were, what would people really do, and how would they screw it up?

Andy Weir (MARS Big Thinker; bestselling author of 2011’s The Martian and 2017’s Artemis): I don’t deal with the “creative” side of the show, only the non-fiction side. I’m a space dork, and for The Martian, I was sitting around thinking about how we could do a manned mission to Mars — not even for a book, but just imagining it. I was thinking about all the things that could go wrong and yet still have the mission go on without having it abort. I created an unfortunate protagonist (laughs), and had him go through all of it! Now we’re dealing with some similar issues on this show. I did make a prediction in my book that there would be no liquid water found on Mars, but I was clearly wrong about that! (all laugh)

Petranek: The secret to living on Mars is to make it a little more warmer. You have all the CO2 that’s trapped as ice on Mars, a lot of which evaporates in the summer. But if you can make the atmosphere thick and full of CO2, you will get a greenhouse effect on Mars. Then you will get water melting on the surface, and at least it will make equators and rivers and lakes, and make agriculture possible.

The big bugaboo on Mars — and it could take a thousand years to solve this — is what’s in the atmosphere. Maintaining a balance of oxygen around 21 percent on another planet and having an inert buffer gas around it like nitrogen is really part of the far future. The rest of it is really more possible in a shorter amount of time.

Mettler: What research did you do in terms of sound and how it would travel between people trying to communicate with each other on Mars, and how sound would travel on and over the planet’s surface itself?

Petranek: Sound travels by bouncing from molecule to molecule to molecule, and there are not a lot of molecules in the air on Mars. It’s 1 percent of the air’s density in the atmosphere on Earth. Presumably, if you sent something out at 100 decibels and you were 1,000 feet away, it would be 1 decibel at that 1,000 feet later. So, radios are a really good idea on Mars.

Mettler: And ones with big volume knobs too, apparently. (all laugh)

Weir: Also, sound would go through the ground surface as well, for the most part.

Petranek: (nods) Yes. Elephants actually do well with that.

Weir: I didn’t know that!

Professor Michio Kaku (MARS Big Thinker; futurist and physicist; author of 2011’s Physics of the Future): We’re talking about a very different ecosystem on Mars. First of all, on the Earth, we’re creating too much carbon dioxide, which is causing the Earth to heat up. The atmosphere on Mars is almost pure carbon dioxide [i.e., CO2]. In fact, it needs a greenhouse effect, or it would be even colder without CO2. We could inject methane and other greenhouse gases in an effort to stimulate it. And if we’re trying to create a terraform on Mars, we may look at Earth as a negative example of how we’re terraforming our planet. On Mars, we’d want to look to create an ecosystem that’s more hospitable to humanity — but it has to be done very carefully. I mean, look at the mess we’ve made here on the planet Earth!

Lucianne Walkowicz (MARS Big Thinker; Astrobiology Chair, Kluge Center of the Library of Congress; Astronomer at Adler Planetarium in Chicago): It really is difficult to get a warming effect on Mars because it is such a different place. Even if you could put all of that carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and make it enough so that you could have liquid on the surface, it would still be incredibly dry, and the water would evaporate and be lost to space. For all our ideas about what we’d like to do there, we underestimate Mars and what a complicated thing a planetary system really is. It’s really hard to protect yourself from the radiation and be able to walk around on the surface and do all the tasks you see people doing on the show.

Kaku: If you remember the movie 2001, where were all the humanoids located? They were underground — and that’s where you could live on Mars initially, given that we know where all those lava tubes exist. Going underground would shield you from all sorts of havoc related to cosmic radiation and solar flares.

Mettler: How about the auditory effects? How will people be able to talk to each other, based on the atmospheric hazards you’ve outlined?

Walkowicz: The atmosphere on Mars is so much thinner, but in a habitat, it would be about the same in terms of the density of the air because the pressure would be about the same, so it would be roughly similar to talking here on Earth. But if you were in that atmosphere that was a lot thinner, sound doesn’t travel as far, so you wouldn’t be able to shout to people who were further away. And in terms of any short-term exploration, you would still be in a spacesuit anyway, and you’d have to be closer together to hear those sounds.

Kaku: Being in a spacesuit is identical to being on the Earth. Sound is going to be the same; air is going to be the same. Everything is going to be identical since you’re living in a controlled spacesuit, but gravity cannot be corrected for because of Einstein’s relativity principle. Therefore, it does means that sound is not a problem. You can have your radio and be in constant email and constant Wi-Fi contact with everybody else, right there inside your spacesuit because you have an Earth-like environment in there.

Mettler: So, we could conceivably have live concerts on Mars? Would people even be able to hear anything played on a musical instrument of some kind?

Kaku: As long as you’re inside a sealed container without atmospheric pressure, there’s no problem. It’s the same.

Mettler: Take that, Coachella! (all laugh) I want to put the following question to Season 2’s core acting troupe — what’s your personal favorite song about space?

Jihae (plays both Hana Seung, Mission Commander of International Mars Science Foundation’s [IMSF] Olympus Town, and Joon Seung, Former Secretary General of IMSF): “Life on Mars.”

[“Life on Mars” is, of course, a key track on David Bowie’s 1971 album Hunky Dory that yearns about the more cosmic possibilities in life beyond the mundane day-to-day.]

Evan Hall (plays Shep Marster, Operation Supervisor, Lukrum Mining Colony): Yeah, the same!

Jeff Hephner (plays Kurt Hurrelle, Commander of Lukrum Mining Colony): Ahh geez, you took mine. (slight pause) “You Are My Sunshine.”

[“You Are My Sunshine” was written in 1939 and has been a standard ever since, covered by thousands of artists over the years.]

Mettler: Or should that be “You Are My Sunspot”? (all laugh) Given the opportunity, would any of you go to Mars yourself?

Jihae: No way!

Hall and Hephner (concurrently): Yes!

Walkowicz: I think I would, yes, as long as we establish a sustainable outpost. Would I go to Mars if it was for some kind of reality TV show? No. Have you seen the kind of people who are on reality TV? (all laugh)

Kaku: To quote Elon Musk, I would like to go to Mars — but not on impact! I’m a coward when it comes to this stuff since rockets misfire all the time and astronauts are trained as fighter pilots, so it may not be for me.

But the universe is our proper home. And in the long term, the law of physics dictates that one day, the Earth will be destroyed. We have no choice in the matter!

Petranek: Landing on Mars may be the greatest thing we do as a people. Remember when we landed on the Moon? People literally turned to each other and said, “If we can do this, we can do anything!” I think people landing on Mars would reinvigorate society, and reinvigorate science. The most fascinating thing I can think of is a human being landing on another planet that’s 250 million miles away. It’s the height of our ability to be visionaries.