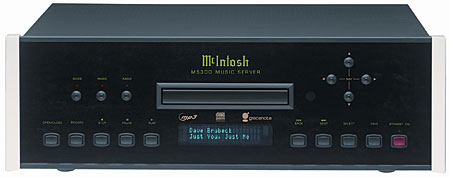

McIntosh MS300 Music Server Page 2

The Net

In order to use the MS300 properly, it must be connected to the Internet. Some of the information stored and displayed on the server about each title (particularly the cover art) is downloaded from the Gracenote disc lookup service on web. An Ethernet port is provided on the back of the MS300 for this purpose. A high speed Internet connection is strongly recommended, but a dial up link may also be used. The latter requires an external Modem (not included).

The system could not find the cover art on a surprising number of the 80 CDs I loaded onto the server in the course of this review. In this event, it simply uses a generic, pre-loaded cover, a variety of which are provided for a number of genres, like classical or jazz. Admittedly, a lot of the titles I chose are far from the mainstream. But the system did find the covers for a few rarities, such Songs of the Sephardim, on Dorian Discovery.

Updates to the system software are also downloaded over the Internet link, either automatically or manually. And because the MS300 also has its own built-in web server, it may be remotely controlled over a home network using a standard web browser. The MS300 can also stream MP3 music files to the web browser.

Then there's Internet radio. The MS300 can receive it, catalog stations, display a list of stations on its Radio Guide, add, delete, and edit stations to the Radio Guide, and play them back over your system. It's a nice feature, despite the limited audio quality this source offers, and fine for news, weather, sports, and talk. But I doubt if many readers will use it as a primary music source.

One obvious shortcoming of the Internet radio feature is that you can't record the radio content, either on the hard drive or a CD, for later playback at home or in your car. This limitation is the result of copyright concerns.

The MS300 comes with a generic, universal remote that serves the purpose but has far more buttons than you need. Many of the most used buttons are very small and labeled with tiny letters. I suspect that most MS300s will find their way into custom installations with upscale touchscreen remotes. And for operations more easily done with a keyboard input (such as loading the Web address for a favored internet radio station), a wireless keyboard is provided.

You can back up all the music on the MS300's hard drive onto an external computer with the required storage capacity (a very large hard drive).

Issues

I had two goals in reviewing the McIntosh MS300, to find out how easy it is to use and how good it sounds.

On some recordings, but by no means all, two subsequent tracks would run together without a distinctive break between them, even occasionally cutting off an instant of the music either at the end of one track, the beginning of another, or both. This was first evident when I assembled a few playlists of tracks from different recordings. But I noticed it later on the full albums themselves. This may be a glitch in the software, or perhaps a minor misalignment somewhere in our sample. It appeared more likely to occur on tracks that end and begin abruptly, or which have little separation to start with. There is no provision to configure the system to automatically add an brief gap between songs. I also noted an occasional dropout in the files from the hard drive. While neither of these glitches happened constantly, they will certainly annoy some listeners.

The Music Guide also has trouble automatically cataloging some categories of music, classical in particular. In the artist listing, it sometimes filed the selection by orchestra, sometimes by composer, and sometimes by conductor. And the Guide could not always clearly distinguish between several recordings of the same piece of music. If you load in 10 recordings of Beethoven's Fifth, for example (and many serious collectors may have that many) several of them might be identified only as Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. Fortunately, you can manually edit the Guide entries to read any way you like using either the remote control or the wireless keyboard. The challenge may be identifying each of several entries after you've loaded them in but before you've had the chance to edit the text. The editing could be tedious if you have a large classical collection, but at least you have the option to do it.

In the Listening Room

More important than any of this, however, is how the McIntosh MS300 actually sounds. I did most of my listening using a direct coaxial digital connection from the McIntosh to a digital input on the Denon AVR-5805 AV receiver.

The first FLAC files I played were Andreas Vollenweider's Caverna Magica and Book of Roses. The opening effects on Magica (people rummaging around in a cave) were striking, with excellent depth. Subsequent cuts on both recordings showed a fine balance. I initially had no real complaints. The sound was warm and rich, but with no shortage of detail. At one point I remarked in my notes that Roses had never sounded better to me before, though to put that in context, I had never before listened to it on this specific system, in this room, either.

Other FLAC recordings were similarly impressive. When I played back the CDs of the same music on the Pioneer Elite DV-59AVi universal player (also with a digital link to the receiver) they sounded noticeably brighter and more detailed, though the detail was often at the expense of the complete musical picture. I was nearly always conscious of the detail, while from the McIntosh FLAC files it was still there, but more subtle.

Still, this was my first inkling that something may have been lost in the transfer to FLAC files on the MS300. I know, I know. They're supposed to be bit for bit copies—I have no way of verifying that, but have no reason to doubt it. And bits is bits, right? Digital perfection, and all that.

Those who believe that the digital outputs of two players carrying the same bitstream must by definition sound identical should, at this point, feel free to play among yourselves. But comparing one player to another, even from those digital outputs, introduces random variables into the mix. In this case there was a more direct route to comparing the original to the server version: playback of the original CD on the McIntosh's own CD-R/RW drive and comparing that to the output from the ripped FLAC file of the same recording.

The result: they did not sound the same. The FLAC files remained easy to listen to, inoffensive, and clearly were still good recordings assuming the original CD was well engineered (not all of the discs I loaded onto the hard drive were equally pristine to start with—a deliberate choice). But there was no question in my mind that the original CDs sounded better. The differences varied from recording to recording, but the FLAC files sounded subtly more homogenized through the midrange and less airy and on top.

These differences were particularly evident on recordings with a lot of delicate high frequency detail. The All Star Percussion Ensemble (Golden String GS CD005) was a case in point. At first listen, the subtle, delicate details at the beginning of "Carmen Fantasy" sounded fine. The dozens of different instruments in this recording could be clearly distinguished, and I had no complaints about the depth and imaging in the soundstage.

But there was no escaping the fact that the original CD on the McIntosh dug deeper into the details, without sounding as bright or obvious about it as the Pioneer had. The hollow nature of the castenets, the delicate buzz of a lightly struck hi-hat, and the subtle timbres of all the instruments simply sounded more real.

But these comparisons, on a wide range of music, also clearly showed the McIntosh to be a superior CD transport, in addition to its ripping and music storage capabilities. I also listened briefly from its analog outputs, and had no reservation about its CD playback quality there, either. Whether or not such an analog connection will sound better than a digital link will depend largely on the quality of your pre-pro or receiver's digital-to-analog converter compared to that in the MS300—or whether or not your receiver even allows for a direct analog pass-through (some do not).

I also found that recording the FLAC files onto a CD-R (either a complete CD or a compilation you have created) produced a further slight loss in quality. Producing the FLAC file from a CD involves some digital manipulation of the data; recreating a duplicate of that FLAC file on a recordable CD involves additional manipulation as the file is converted back to PCM for playback on any CD player. These operations are theoretically lossless—again, the bits should be the same—but for whatever reasons, the transfers were not audibly seamless.

You can also transfer MP3 files you may have saved on the MS300's hard drive onto a CD-R/RW, either as data files (playable only on MP3-capable players) or audio files (playable on most regular CD/DVD machines). But these are clearly not lossless.

And speaking of MP3, how do CDs compressed into MP3 files sound on the McIntosh? In this case, any losses incurred are the direct result of MP3 limitations and have nothing to do with the basic quality of the MS300, but inquiring minds want to know. At 320kbps, the recordings sounded okay, but with some material they could sound slightly edgy and lean, with the bass a little AWOL. The comparison with the CD was night and day. The original was cleaner, more full-bodied, and less processed-sounding.

But the 320k MP3 sound was not actively bad. On most recordings, in fact, the degradation in sound quality was subtractive and the sound remained very listenable. I would pick no argument with a music lover who might use 320K MP3 to maximize the capacity of the hard drive—though he or she is unlikely to be a serious audiophile.

But I can't imagine how anyone serious about music would use 128k. Again, the losses were not of the sort that makes bad analog sound annoying—no fuzzy distortion, no sense of overload, no added noise. But the loss of weight and body in the sound, the dry highs, and the way it turned the most compelling music into a cardboard cutout of its former self, were depressing. Depressing not because it's available on the McIntosh; it probably doesn't add much if anything to the cost, and no one will force you to use it. But depressing to realize that there are probably more people listening to music this way today than directly from a good quality, uncompressed digital or analog recording.

Conclusions

As the first music server I have tested, in all fairness I have to reserve judgment on how the McIntosh compares with its peers until I test a few more. I plan to do that: let's call it the search for the flawless hard drive playback.

While the MS300 is not perfect, it does offer McIntosh's superb build quality combined with exceptional convenience and, in FLAC mode, a level of sound quality that will satisfy most music lovers. Most of the CDs I ripped onto its hard drive were recordings I hadn't listened to in a long time. They might have been on my shelf, but were well out of mind. Does it matter if they sound marginally better played back directly if I never listen to them at all because they're hard to find—or even worse if I've forgotten I even have them? Or is it more important that the music they hold be available to me for instant access? That's a question each potential buyer—and even dedicated audiophiles—might want to ponder.

Highs and Lows

Highs

• Superb direct CD playback

• Huge storage capacity

• Flexible access modes

Lows

• Some audible loss with ripped files, even in FLAC mode

• Occasional dropouts from hard drive playback

• Tracks do not always end or start cleanly