Now That's Television Page 2

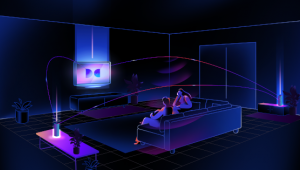

At one point, I could plainly hear the surround speakers reproducing audience-member and stage-hand voices while presenters were at the podium. There's a lot of activity on stage during the Grammys. While an award recipient is giving his or her speech, crew members are setting up the next act just outside of the camera range. A lot of that sound made it through the mix and helped to maintain HDTV's virtual-reality feel.

At one point, I could plainly hear the surround speakers reproducing audience-member and stage-hand voices while presenters were at the podium. There's a lot of activity on stage during the Grammys. While an award recipient is giving his or her speech, crew members are setting up the next act just outside of the camera range. A lot of that sound made it through the mix and helped to maintain HDTV's virtual-reality feel.

Once the performances started, the surrounds relayed a good mix of natural echoes and ambient crowd sounds. The mix seemed a bit conservative at the beginning; however, about 30 minutes into the show, things really took off when the New York Philharmonic and Coldplay performed "Politik," and my room filled up with sound. Bruce Springsteen's

performance of "The Rising" was quite emotional, and Eminem's turn on stage really had the house jumping. As a tribute to Joe Strummer and the Clash, Springsteen, Steve Van Zandt, Elvis Costello, and Dave Grohl from the Foo Fighters really got into it with a rousing performance of "London Calling."

Still, one of the most enjoyable moments came when Norah Jones, who copped several awards, including Record and Song of the Year, performed the low-key "Don't Know Why" and sounded as if she were performing in the same room with me. Ditto for the surprise duet of "Sounds of Silence" by Simon and Garfunkel and an even-more-delightful pairing of James Taylor and Yo-Yo Ma. When it comes to music, sometimes less is more.

Still, one of the most enjoyable moments came when Norah Jones, who copped several awards, including Record and Song of the Year, performed the low-key "Don't Know Why" and sounded as if she were performing in the same room with me. Ditto for the surprise duet of "Sounds of Silence" by Simon and Garfunkel and an even-more-delightful pairing of James Taylor and Yo-Yo Ma. When it comes to music, sometimes less is more.

The second revelation? Awards shows like these are a no-brainer for HDTV. The stage's size and shape are simply wasted in a 4:3 aspect ratio. Thanks to good camera work and that top-notch 5.1 mix, I did feel like I'd been sitting 20 rows back, dead center, in Madison Square Garden.

If this show came up at all short in production value, blame that on the decision not to use a strong host. Instead, a steady parade of eclectic performers and industry figures came up to the stage to introduce performances or announce winners. More than once, a presenter lost sight of the TelePrompTer and just ad-libbed. Even Peter Gabriel seemed a bit confused when, after the last award had been given away, he blurted out, "Well, that's it! Goodbye!" and the 45th Grammy Awards were history.

The Oscars

Thirty days later, it was ABC's turn to step up to the plate with the Oscars (or, as they are known in the broadcast industry, the Super Bowl for Women). There was much anticipation, as ABC had announced back in early January, before any of ABC's or ESPN's 720p production trucks had even been delivered, that they would broadcast the event in 720p. They upped the ante by announcing that a single HD mobile-production truck would handle all of the switching and mixing, preparing a 4:3-aspect-ratio conversion of the HD camera shots and clips for the regular ABC analog broadcast. Talk about betting all of your chips on one hand.

If the Grammys were all about the audio, the Oscars were definitely all about the video. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) and ABC coproduce the Oscars. Once both organizations had agreed to a high-definition production format, an immediate question popped up: how to best show a wide variety of film clips in their native aspect ratios in both the HD and SD telecasts.

If the Grammys were all about the audio, the Oscars were definitely all about the video. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) and ABC coproduce the Oscars. Once both organizations had agreed to a high-definition production format, an immediate question popped up: how to best show a wide variety of film clips in their native aspect ratios in both the HD and SD telecasts.

Since the HD truck would be at the head of things, an aspect-ratio conversion would be necessary for analog-TV viewers. In an aspect-ratio conversion, a center 4:3 slice of the 16:9 HD image is downconverted to 480i, which ensures that both the HD and SD viewers see a full-screen program with no letterboxing. It sounds simple, but there's a catch. What happens when you have film clips that are in different aspect ratios like 1.33:1, 1.85:1, and 2.35:1? If you set up these clips to fit a 16:9 frame, the SD version clips off too much of the sides. If you favor the SD broadcast, the HD viewers will see a big black frame around the images.

The solution, according to the Oscars' lead engineer Tad Scripter, was to prepare all of the film clips in both standard and high definition and run both versions simultaneously from one truck. This included clips of the Best Picture nominees, the diamond-anniversary sequence at the start of the show, and the in-memoriam sequence.

For the event, Hollywood's Kodak Theatre was equipped with brand-new Thomson progressive-scan HD cameras, one of which was mounted on the SpiderCam aerial-image system that was used in last summer's blockbuster Spider-Man. The crew mounted several cameras in high-angle positions on cranes to incredible effect, lifting out and over the audience to show the stage and several seating levels.

For the event, Hollywood's Kodak Theatre was equipped with brand-new Thomson progressive-scan HD cameras, one of which was mounted on the SpiderCam aerial-image system that was used in last summer's blockbuster Spider-Man. The crew mounted several cameras in high-angle positions on cranes to incredible effect, lifting out and over the audience to show the stage and several seating levels.

"Our HD production truck was the NEP SS-20, which will also be used for ESPN HD sports," said Scripter. "[Director] Lou Horvitz sat in the Denali Gold standard-definition truck that's been used for many years to handle the analog broadcast and called the show using a remotely connected Thomson HD switcher located in the SS-20 truck. Nineteen different cameras were used, along with numerous Thomson Profile HD and SD hard-drive video servers."

ABC has become known for supplying 5.1 mixes for as many of their sports and prime-time shows as possible, and Ed Greene (who did the production mix for the Grammys) handled the 5.1 console again. He also sent a two-channel mix to ABC's standard-definition remote truck. From another remote truck, Jay Vicari downmixed the Bill Conti–led orchestra and sent Greene a two-channel mix with some low-frequency effects.