Progressive-Scan or Progressive Scam?

Conspiracy theories are like computer problems—almost everyone has one. From JFK's assassination to the demise of TWA flight 800, it's rare that everyone will accept the simplest explanation as the truth. Consumer electronics has its fair share of conspiracy theories, as well. They may not be as complex as a Louisiana district attorney's triangulated-bullet-trajectory theory, but they exist, nonetheless. What do you expect to happen when a large number of obsessive-compulsive personalities have too much free time and join a chat room?

A progressive-scan DVD player (top) offers a 480p output with far fewer processing steps than a normal, interlaced player that's connected to an external line doubler or scaler (bottom).

Rumors abound that progressive-scan DVD players aren't truly progressive. This is absolutely true. These same rumors argue that existing "progressive" DVD players use internal line doublers to create the progressive image. This, too, is true (and has been stated by nearly every manufacturer). In fact, former HT editor Brent Butterworth exposed the whole process in our October '98 issue. This causes many people to wonder whether or not progressive-scan players are worth buying. In our opinion, absolutely—even the cheap ones. After I explain what "interlaced" and "progressive" actually mean and what the different types of progressive DVD players are, you'll understand why.

There are plenty of characters in this conspiracy, but everything starts with the two main culprits: interlaced and progressive. NTSC, the four letters we banter about when we don't feel like saying "the TV system that the vast majority of people watch every day," is an interlaced system. This means that the system's 480 horizontal lines are drawn from the top to the bottom of your screen every thirtieth of a second. However, since the frame is interlaced, it's split into two fields (smaller, faster frames), each containing half, or 240 lines, of the frame, displayed every sixtieth of a second. The image is divided, as if raked by a comb, between even and odd lines. Every other field scans the lines between those of the preceding field. While there are only 240 lines on the screen at any one time, the fields are drawn so quickly that your eyes blur them together and give you the impression that you're seeing one frame. In order for DVD to be compatible with this type of system, the player's output is interlaced. The problem is that, on displays larger than 32 inches, interlaced scan lines become obvious, especially when your eye follows vertical motion in the image. Try looking at the scan lines on the TV between the gaps of your fingers, then wave your hand up and down. The line structure becomes obvious.

On the other hand, a progressively scanned image draws all 480 lines of the image completely, in one pass, every sixtieth of a second. This creates a smoother, more-solid image with more apparent resolution. Due to the advent of larger and larger television screens, as well as HDTV, manufacturers have found the need to make TV monitors that can accept and display a progressively scanned image. While these TVs have mediocre line doublers built into them, DVD is a potential source for native progressive images.

If the CIA had anything to do with JFK's assassination, they certainly aren't telling. Film technology, however, definitely has something to do with proper progressive images, and we found some techs who would tell. According to our sources, since most DVDs originate from film, they can be (and usually are) recorded as a progressive image. The image on the disc contains 24 frames per second, which corresponds to a film's original 24 frames. As with NTSC images, though, a process called 3:2 pulldown is used in order for the 24 frames to keep time with video's 60 fields. As described in diagrams C and D, 3:2 pulldown splits every film frame into two interlaced fields and then adds an additional field for every other film frame. The result is two fields that correspond to one film frame, followed by three fields of the next frame, then back to two fields, and so on. With TV broadcasts and videotapes, this process is added at the studio when the film is transferred to video. With DVD, it's added by the player so that the output is compatible with the vast majority of TV sets. The program producer is supposed to mark the data stream with flags to tell the player when to put in the additional fields. As I'll discuss later, this doesn't always happen.

A true progressive-scan DVD player would bypass the interlace step and output the original progressive signal, but it would still have to add the 3:2 sequence. Unfortunately, for incredibly technical reasons, almost none of the existing players that we know of actually accomplish this seemingly simple task. On the other hand, some computer manufacturers claim that their progressive DVD cards can do this, as can one consumer manufacturer's standalone player. For reasons I'll explain later, it's impossible to tell the difference and possibly not even a good idea.

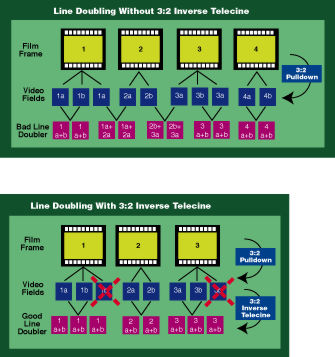

So, how do the consumer manufacturers get away with saying their players are progressive? Simple: They output a signal that's identical to what you would get if the player were truly progressive. How? The vast majority of manufacturers take the interlaced but still digital output of the player's MPEG decoder and feed it directly into a video processor (aka line doubler). This, in and of itself, creates a better picture than you would get from feeding the DVD player's analog output into an external line doubler—be it a separate component or one built into a television. The external doubler must convert its analog input back into a digital signal for processing, then back to analog at the output (see diagrams A and B). By avoiding the unnecessary digital-analog-digital step, the picture stays cleaner and more detailed, regardless of the quality of line doubler used. This is one way that Pioneer's $300 DV-434, which uses a relatively mediocre line doubler, proves to be a value to consumers. While this process may benefit many systems, it doesn't yet compare with a true progressive signal.

Now, there are good line doublers, there are mediocre line doublers, and there are bad line doublers. I generally like to refer to both good and mediocre line doublers as deinterlacers because, in reality, they don't generate new information—they just marry the information that already exists, thus removing the interlace. Remember that each of our film frames was split in two in the interlacing pro-cess. Both good and mediocre line doublers would store both fields in memory, line them up, and spit them out as complete images. (They would actually spit them out twice to keep time.) Bad line doublers interpolate new information between each line and, given the speed of the signal, usually do this poorly. Right now, processors relying solely on this technique are few and far between. Still, none of these images would compete with a true progressive-scan DVD image . . . yet.

To keep the timing correct between 24-frame-per-second film and 30-frame/60-field-per-second video, every other film frame has an additional field, creating a three-field/two-field sequence. Better line doublers/deinterlacers and progressive DVD players recognize and compensate for this 3:2 sequence (bottom). Poor processors do not (top).

The difference between good line doublers and either mediocre or bad line doublers also has to do with the way they handle the 3:2-pulldown sequence. This compensation is often referred to as 3:2 inverse telecine (the opposite of 3:2 pulldown). As the deinterlacer combines each pair of fields, it should notice that fields three and four are from two completely different frames. If it combines these fields, you'll see motion artifacts in the image, most noticeably jagged edges on diagonal lines (see the opening of chapter 2 on the Armageddon DVD). Mediocre processors blend these images to some extent. Better processors will ignore field three altogether and instead will spit out the previous frame an additional time. Therefore, the 3:2 sequence is preserved, and only the correct fields are married together.

Most "progressive" DVD players use a video processor that in some way recognizes 3:2 pulldown. As this is all done digitally, the resulting output is then identical to what you would have gotten had the player been truly progressive and bypassed the interlace step. This is also why we can't tell you whether or not a particular player is truly progressive. There's no way to tell. So, we are willing to call them progressive-scan players. Since the above-mentioned DV-434 does not include 3:2 pulldown, we don't feel that it should be called a progressive player, although it does offer a reasonably good progressive output and has merit of its own.