2:3 or Not 2:3? Page 2

From a 2:3-pulldown signal recorded on a DVD, a player's progressive-scan output must produce a frame rate of 60 fps, twice that of interlaced video, with each progressive frame containing a full set of scan lines, even and odd. There are two primary ways of doing this, each having its own problems.

Weaving takes two successive interlaced fields and reinterleaves them to create a progressive frame. This is the process illustrated in the last row of our diagram, and it works well if the original material was progressive, like a film that has undergone the 2:3-pulldown process, and provided the disc tells the player that it was. How a player interprets a disc's data stream if it has been misidentified is an important aspect of its progressive-scan performance, in addition to how it handles programs that mix original video material with film-based material that was converted to video using 2:3 pulldown.

|

|

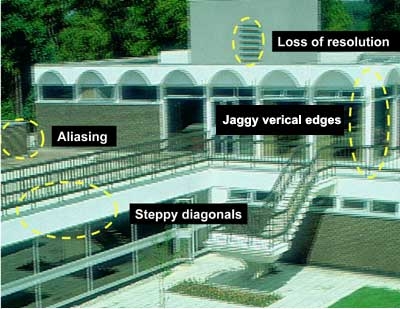

| These film-derived images show some of the artifacts that may result from progressive-scan conversion. On Top, artifacts from "weaving," on bottom, those from "bobbing." A variety of more advanced conversion techniques are becoming available. |

If the original material was interlaced video, not 2:3-pulldown film, weaving can cause the artifacts shown in the first photo above. The existence of these faults is why progressive-scan conversion of video material is more difficult than movies and why some DVD players that look great on films stumble when reproducing live concert videos.

"Bobbing," the normal process for generating a progressive signal from interlaced video, takes a single field and creates a full progressive frame from it by line doubling or line interpolation. It can produce the artifacts shown in the bottom photo, some of which resemble those produced by weaving. The most significant of them are stepped diagonal lines and a loss of vertical resolution.

More advanced progressive-scan con version systems combine bobbing and weaving, depending on the content of the image. Weaving is performed in areas of the picture where nothing much is moving over the course of several frames, increasing the vertical resolution in those areas. Bobbing, or even a form of time-averaging (smearing), over several frames is used in areas with a lot of motion.

Such advanced technology can be found in some standalone line doublers and rescalers, and it's slowly finding its way into DVD players. It's not enough simply to look for a DVD player with 2:3-pulldown capability - all progressive-output players do it in some fashion. What you want to see in DVD data sheets and advertisements is some indication that something more than simple bobbing and weaving is going on. While you can look for the phrases "field-adaptive" or "motion-predictive," you won't always find them since there's no standardized terminology for the various advanced conversion techniques. That some standard terminology would emerge is, as the Bard would say, a consummation devoutly to be wish'd.