Bass-ic Training

In the early days, people who sought full-range sound typically needed very large speakers. However, because of placement issues, cost, and the vast living-room real estate these speakers required, not to mention the subsequent aesthetic disapproval they inspired, the majority of hi-fi lovers were forced to accept smaller and sonically inferior speakers. With the advent of home theater, the need for low-frequency sound became apparent. In the process, the benefits a subwoofer offered for music reproduction became more widely appreciated. In this month's Boot Camp, we'll cover how subwoofers work, the benefits they offer, and what to look for when purchasing one for your system.

In the early days, people who sought full-range sound typically needed very large speakers. However, because of placement issues, cost, and the vast living-room real estate these speakers required, not to mention the subsequent aesthetic disapproval they inspired, the majority of hi-fi lovers were forced to accept smaller and sonically inferior speakers. With the advent of home theater, the need for low-frequency sound became apparent. In the process, the benefits a subwoofer offered for music reproduction became more widely appreciated. In this month's Boot Camp, we'll cover how subwoofers work, the benefits they offer, and what to look for when purchasing one for your system.

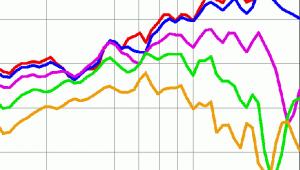

First of all, true subwoofers function in the lowest octaves of the audible frequency range, the most physically difficult region to reproduce. Due to the long wavelengths of these low frequencies, a subwoofer requires a large woofer, big cabinet, or massive amplifier. Hoffman's Iron Law, described by Henry Kloss in the mid-1950s and later turned into an exact mathematical formula by engineers Thiele and Small, governs the behavior of woofers. Essentially, it says that a woofer's efficiency is proportional to the volume of its cabinet and the cube of the lowest frequency it can produce before losing relative level (aka the cutoff frequency). Take, for example, a woofer whose response is flat down to 40 hertz in a 2-cubic-foot enclosure. To make its response flat down to 20 Hz, you must either increase the cabinet volume by eight times (to 16 cubic feet) or use eight times the amount of amplifier power to achieve the same listening volume. Given these requirements, you can see how difficult it can be to get respectable low-frequency response from small "full-range" speakers.

- Log in or register to post comments