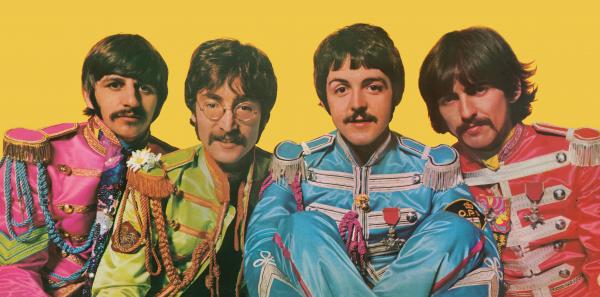

Giles Martin & Little Steven on 50 Years of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper

For on this storied day of June 1, 1967, The Beatles transformed the album format into an artform virtually overnight when they released the long-anticipated Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

To commemorate this storied occasion, The Beatles released a kind of Pepperland Suite of Sgt. Pepper Anniversary Edition packages via Apple Corps Ltd./Capitol/UMe last Friday, May 26, 2017, including an all-in multi-disc box set, double LP 180-gram vinyl, double-disc CD, and high-resolutions downloads. The album proper is newly mixed by Giles Martin and Sam Okell in stereo and 5.1 surround sound at 96kHz/24-bit. The collection has also been expanded with early takes from the studio sessions, including no fewer than 34 previously unreleased recordings.

“It’s crazy to think that 50 years later, we are looking back on this project with such fondness and a little bit of amazement at how four guys, a great producer, and his engineers could make such a lasting piece of art,” Sir Paul McCartney noted in his newly penned introduction for the Sgt. Pepper Anniversary Edition. Also in that included book, Ringo Starr rightly observed, “Sgt. Pepper seemed to capture the mood of that year, and it also allowed a lot of other people to kick off from there and to really go for it.”

Since that day of release in 1967, there has been much debate over which version of Sgt. Pepper — or, as some refer to it, Sgt. Pepper’s in its wholly correct possessive form (even though the apostrophe doesn’t appear on Ringo’s bass drum on the album cover) — is “the best” or “the correct” one, though many of us can agree The Beatles themselves and their producer, the late Sir George Martin, always intended it to be heard in mono since that’s how they worked on it in the studio. That said, a generation of listeners absolutely swear by the stereo mix as helmed by Geoff Emerick, and the box set gives us perspective on both the original two-channel version and the updated stereo as overseen by Martin and Okell. Naturally, I’m also quite partial to the hi-res 5.1 mix done by Martin that’s on the box set’s included Blu-ray — especially the beautiful, all-channel uplift-to-the-heavens engulfment of “A Day in the Life,” which instantly became one of my top surround system demo tracks.

To get a relatively balanced perspective on Sgt. Pepper at age 50, I decided to get some answers in stereo — that is, from both sides of the Pond. I first sat down with the aforementioned Giles Martin, 47, in New York, to discuss what went into the box set’s mixing mindset and overall presentation. Then I got on the line with Little Steven Van Zandt, 66, a key member of The E Street Band and the founding father of the Underground Garage radio format and SiriusXM channel to get his more mono-centric U.S. perspective on things. Regardless of which way you lean toward re your own preferred listening method for Sgt. Pepper, one thing I think we can all agree on: A splendid time is guaranteed for all.

Mike Mettler: So, Giles, the million dollar question is: Why remix Sgt. Pepper at all?

Giles Martin: It’s a good question. You have to imagine the extraordinary detail involved in mixing something like this. “Wait, where does the snare drum go? Where should it go?” (both laugh)

But you’re right. I suppose we should take a moment and talk about why the hell we did do this, because, let’s face it, it’s not a bad-sounding album, and it did do pretty well.

First, when Sgt. Pepper’s was made, it was an ultimate collaboration between the four boys, my dad, and Geoff Emerick. And they were working toward making something and almost rejecting their previous fans’ expectations of them, by doing something totally new.

I know from my dad it was one of the most extraordinary experiences of his life once they got to the end of mixing the mono, and mono was the thing. They also weren’t just mixes; they were performances. The boys took turns working the faders, and were very involved at all times.

And as you know, the stereo mix was done very quickly. The stereo was almost an afterthought. but everyone listens to the stereo now. So our thought was that we almost make a stereo version of the mono. Our view was, let’s listen to what the band did. Let’s listen to how they made the mono, and let’s come up with something new.

Mettler: Was one of your other goals to introduce the album to a younger generation of listeners?

Martin: Yes. I tell my kids and other people tell their grandkids about this album that appears as but one entry in this glorious world of jukebox music where everything is available nowadays, and their reactions can often be like, “This album changed the world? REALLY??”

And let’s face it — the band was 24 and 25 years old when they made this album, and they’ll always be 24 or 25 when they sing this album. So there’s a sort of vibrancy we got after going through the various generations of tape to get here. There’s an immediacy you get and feel from the tracks you now hear in this new mix.

Mettler: I know John Lennon had a particular set of instructions regarding how his vocals appeared on the album.

Martin: My dad said John was always obsessed with, as he put it (affects the lower-tone of how his father spoke), “screwing up his voice,” and it is kind of cool what they did with it on “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds.” It’s heavily ADT’ed [automatic double-tracked]. Sam Okell, the mixing engineer I worked with, is just great. He spent days, just days, with a varispeed knob, just sitting there, working with those ADT things. (chuckles)

The original mono version of “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” actually sounds more three-dimensional, and the original stereo doesn’t have that feel. In the new mix, now you hear the keyboard sound in stereo as well.

Mettler: Did you and Sam have relatively free rein in how you mixed things?

Martin: The beauty of it is — and the humbling thing of doing it was — there were so few people working on it. There was myself and Sam, and then there were The Beatles, and that’s it. There weren’t any forums of people there giving us grades, or waiting for the single. (both laugh) The Beatles always dealt with boundaries and how they could push them, and we had to push boundaries ourselves.

The other thing we were asked to do was to go through all of the outtakes and add extras to the album — and we came across some interesting stuff, actually. What we’ve tried to show with the outtakes is Sgt. Pepper’s wasn’t created from some sort of cloud that was floating around, and then it was plucked from the air. It was made by four guys, and my dad, and Geoff Emerick. They were in the studio together making sounds, and it was very sort of granular. It’s people making noise — making beautiful noise — and the complexity of it was based on live performance.

Mettler: I’ve heard you tell an interesting story about the making of “Fixing a Hole.”

Martin: When I went to see Paul [McCartney] to play him the mixes. I played him “Fixing a Hole,” which was a struggle to mix. As you know, they recorded much of it down at Regent Sound Studios rather than EMI [i.e., Abbey Road]. Paul told me the story of how this guy showed up and said, “Hello, I’m Jesus.” So he let him in, because you can’t turn down Jesus! (both laugh) Paul told him, “Look, I’m going to go record with the boys.” The studio was a very small space and he walked in and said to the boys, “Hey guys, this is Jesus, and he’s coming into the session.” So they recorded “Fixing a Hole” with Jesus, which is always handy. (more laughter)

Mettler: “A Day in the Life” didn’t always have that iconic final E chord crescendo, did it?

Martin: No. For the end of “A Day in the Life,” they knew they needed the E chord resolve to finish the album, but the first thing they tried was a vocal chord. It’s one of the outtakes, and it is kind of fun to hear, because this shows you that even geniuses like The Beatles can have bad ideas. And that’s the key to all of this — allow yourself to have bad ideas, but choose the good ones. And The Beatles just threw ideas at everything.

We had the privilege of going back to previous generations of tape to hear 4 tracks that bounce over to 1, and then back again and again. And what that means is we not only had the ability to mix with more tracks than they had at the time, we were also mixing from the earlier recordings, so we had a much clearer signal path. The benefit of that is, for one thing, you get a much more dynamic drum sound — which means Ringo’s happy. And the second one is it gave us a choice for how to pan things.

Mettler: Your final assessment of Sgt. Pepper, in two sentences?

Martin: What it showed me is that they played it as a band. Sgt. Pepper’s is so well organized, and they knew how to play all the right sounds for it.

Mettler: Stevie, let’s turn to you. What can you tell me about the initial impact of Sgt. Pepper in the United States?

Little Steven: For that first week in June that it came out, man, I’ve never seen the Western world so unified, so completely taken with one single piece of work. It was coming out of every single restaurant, clothing store, record store, and the cars that went by — I’m not kidding. I mean, you went up and down MacDougal Street [in New York City], and you would not hear anything else.

Mettler: I’m also glad we have the proper mono version of it, which I know is something you championed having out there for the longest time.

Little Steven: That was it, yeah. I spent years, literally years, talking to Neil Aspinall, God bless him, the guy who was running Apple for many years before Jeff Jones. It took me, I’m not kidding, it must have been 5 or 6 years of conversation before he got tired of hearing me. (both laugh) And right before he died [on March 24, 2008], he decided to put them out.

I kept telling him, “Neil, listen — you’ve gotta understand. These are the mixes that the band and George Martin did. And then they left the studio, and the assistant engineer [Geoff Emerick] did the stereo mix, and it was a gimmick, and nobody gave a sh-- about it. And that’s been the only thing people can hear for 40-bleeping-years!” (chuckles) So it was like 40 years before people heard the actual mixes, you know? I mean, it’s The Beatles of all people, right?

Mettler: “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” came out as a two-sided single [on February 13, 1967], a few months before the album did. Do you feel they should have been on the record itself, or are you a purist and fine with having them as standalones? [Both songs appear in the extended Sgt. Pepper releases.]

Little Steven: Either way, I understand George Martin’s frustration with that, I really can. [The late Sir George Martin said on a number of occasions he would have liked to have seen those two songs appear on the Sgt. Pepper album proper.] But you can’t imagine the album needing anything more, you know? That’s one of the greatest singles of all time, and it was really the beginning of a concept. And it was a concept — even if people say it wasn’t, it really was.

If you look at those lyrics — the lyrics are very, very interesting. Here it is, the real epitome of The Summer of Love is the Sgt. Pepper album, and it completely sounded different than anything before it, or after it. It’s so special, in so many ways. And I know all the discussions about there being more innovation on [1966’s] Revolver, and the songs are better song-by-song on Revolver. I am a fan of all that, and I do agree with a lot of that. But it doesn’t take away the fact that Sgt. Pepper has a magic to it that is simply unexplainable. It really is unique.

And, of course, we were so used to it the way it is, that you can’t picture it being any other way. Those songs feel a little different to me than the rest of the record does. That’s how fast they were progressing at the time.

Mettler: Do you consider those two songs as a kind of “prelude” for what followed with the album itself?

Little Steven: Yeah, that’s one way to look at it. I can also look at it the other way — that single could have come out after the album, and that would have made sense too. They’re two very unique songs in their own way.

I mean, it was a helluva year — you had Sgt. Pepper and that single, and then you had “All You Need Is Love,” which was out a few weeks later. [“All You Need Is Love” was first performed by The Beatles live over a pre-recoded backing track on Our World, the first international live satellite broadcast, on June 25, 1967, and then it was released as a non-album single on July 7, 1967.]

Mettler: I like having those singles as perfect literal bookends to Sgt. Pepper. In general, do you like having full collections like this with outtakes, alternate takes, and surround sound mixes?

Little Steven: I don’t spend enough time with those things because I never seem to have enough time to listen to them, but I do enjoy them; I really do. It’s always interesting to hear them. You really appreciate George Martin when you hear the demos and how the shaping of some of these songs took place, and the job he really did with them. You tend to appreciate that even more when you hear the outtakes and the demos. So it does have a value, yeah.

- Log in or register to post comments