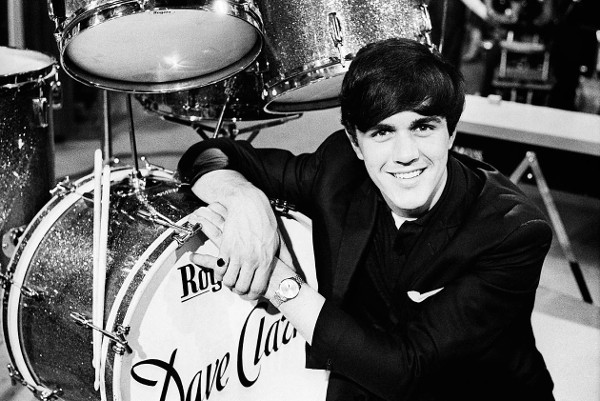

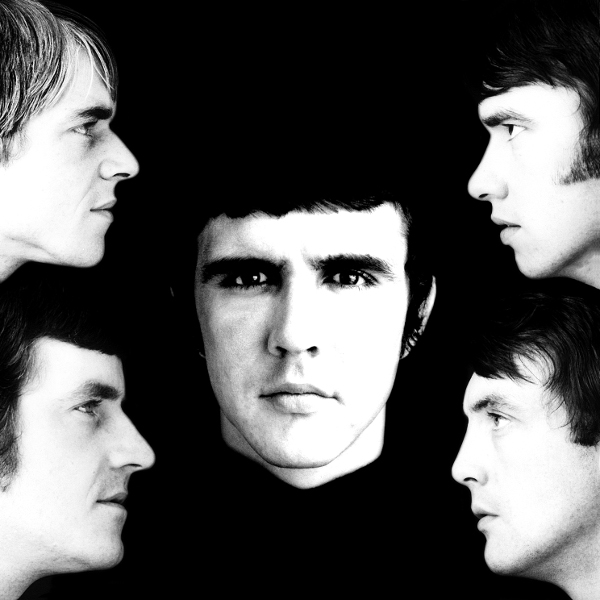

British Invasion Pioneer Dave Clark: Still ‘Glad All Over’

“I just happened to be the guy at the front.”

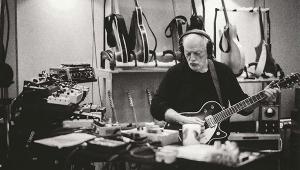

The above understatement is courtesy of one Dave Clark, the innovative drummer and savvy businessman who helmed The Dave Clark Five, the one band that most consistently gave The Beatles a run for their money on the pop charts during the heyday of The British Invasion in the 1960s.

In fact, The Dave Clark Five, a.k.a. The DC5, went on to sell (yes) over 100 million records worldwide, in turn amassing a catalog of hits you know by their titles alone: “Do You Love Me,” “Glad All Over,” “Bits and Pieces,” “Over and Over,” and “Catch Me If You Can,” to name but a few. (The trivia buffs amongst you know “Glad All Over” was the song that knocked The Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” out of the top spot on the British singles charts when it climbed to No. 1 in January 1964.)

In fact, The Dave Clark Five, a.k.a. The DC5, went on to sell (yes) over 100 million records worldwide, in turn amassing a catalog of hits you know by their titles alone: “Do You Love Me,” “Glad All Over,” “Bits and Pieces,” “Over and Over,” and “Catch Me If You Can,” to name but a few. (The trivia buffs amongst you know “Glad All Over” was the song that knocked The Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” out of the top spot on the British singles charts when it climbed to No. 1 in January 1964.)

Clark was shrewd enough to both own and control how his music was released from the very beginning. After the band essentially called it quits in 1970, new, updated, and/or compilation-style DC5 releases in the ensuing decades were quite sparse. That said, Clark did make a brief concession to the burgeoning CD market when he supervised the 2CD, 50-track release The History of The Dark Clark Five via the Hollywood Records label in 1993 (long since deleted).

What was the secret for how The DC5 were able to conjure so many perfect pop gems in the 1960s? “We were always well rehearsed before we went into the studio,” Clark reveals. “I always thought that you treat the studio as something special. If you’re just going to spend all day in there writing and rehearsing one song, you lose out. But for me and for the boys, it was about that special buzz you get when you get to the studio. And then we would always put something down in a maximum of three takes.”

Clark called in from across the Pond to discuss the specific sound he was going for in the studio, the mistake in “Bits and Pieces” and studio fix in “Over and Over” he’s never revealed before, and The DC5’s perpetually strong legacy. Catch us if you can. . .

Mike Mettler: As an audiophile listener, I appreciate that you took the time to make sure All the Hits was done properly on vinyl — which I’m sure must be of great importance to you.

Mettler: People talk about The Beatles and The Dave Clark Five having a rivalry, but I wouldn’t put it quite that way myself.

Mettler: You mean Glad All Over? Oh yeah, I saw it — and bought it on Blu-ray too. It was really quite informative.

Mettler: Yeah, you were like two football teams, in a way. (Clark chuckles) And from what I see in the All the Hits credits, this was all done at Abbey Road Studios. You actually went there to do the remastering yourself, right?

Mettler: And you’ve always had the original masters in your hands or in your own personal vaults?

Mettler: You were cognizant from the very beginning that it was an important thing to own them, even if you didn’t realize you’d be working with them 50 or 60 years later.

Mettler: Right, those “labcoat” kind of engineers. Landsdowne Studios in London is where you recorded originally. How did you come across that as the location to record everything?

We needed a good place to go and record our songs, and it was at Landsdowne. And you always got free studio time at the end to put down your own track. I was blown away by that studio. And the engineer, Adrian Kerridge [who worked with The DC5 from 1963-68], I always thought was magnificent.

Mettler: Right, and you give him some special love in the Hits liner notes too [for his “technical wizardry”]. What pointers did Adrian give you about recording that enabled you to be able to capture such a unique sound from the very beginning?

We had recorded a couple of tracks and had started to really hit it off with Adrian when I asked him to come around to Tottenham Royal, where we were playing to 6,000 people a night. He heard the sound at the gig for a couple of nights, and I said to him that I wanted to get that live sound in the studio, even though it went against all the rules and regulations. When you mastered for vinyl in those days, you could only go up to a certain level — and if you went past that, they wouldn’t press it. But because we were independent, we went way past that — as long as it didn’t distort.

Mettler: You went into the red, but in the right way.

Mettler: It was really verboten in the studio in those days to distort anything and push anything that loud, but you just went and did it.

Mettler: Oh yeah. You were also playing on U.S. military bases and to 6,000 people a night in the days when some artists were playing in front of no more than a few hundred people. Did you feel the difference between going from hundreds to thousands in the audience?

Mettler: Was “Reelin’ and Rockin’” one of the early ones you also tackled around that time?

Mettler: It was what you and other bands were doing in England that brought artists like Chuck Berry back to the forefront, in my opinion. Now, in terms of the physicality of how you appeared onstage, you were literally upfront in terms of your drum positioning. Was that a decision you made early on — to physically be in that particular space, or did it come about in an organic fashion?

Mettler: Right. Your sound then was more in the Fats Domino style, more than people might think.

Mettler: You first heard it on the radio, then decided you had to have it?

Mettler: Your instrumentation was further up in the mix than the vocals were, whereas other records at the time had the lead vocalist way out front and the band way in the back. You kinda flipped that a little bit differently.

Mettler: A lot of The DC5 vocals were in call and response style. Was that coming from a church background, or. . .?

Mettler: When I’m listening to a song like “Glad All Over” on vinyl again after so many years, I like being able to pick up on hearing some of the guitar lines underneath the drums that I didn’t exactly pick up on when I was listening to it on the original vinyl.

When we went to remaster it to CD a few decades or so later, that was the first time I had heard that doubled-output guitar. And then I thought, “Maybe the equipment’s better, because it stands out now” — which is lovely.

Mettler: Especially listening to it in stereo. Speaking of that, in terms of mono versus stereo, did you have a preference either way?

In the early days, Landsdowne Studios was in a basement, in a squash court in this beautiful Victorian building. The echo chamber was the stairwell, where you got the most amazing sound. The only downside was, if you were in the middle of a take and somebody decided not to use the elevator and walk down the stairs, then you had to stop and redo it. (chuckles)

When we went to mix the stereo, the echo chambers had become more sophisticated, and much better. A lot of our stuff had been overdubbed, like the [foot] stamping, or if you wanted to do another percussion sound. The guitar riff that you picked up on is an overdub. But when we went back to the original four-track, that part was missing! It was very easy to redo it and we got it perfect, but it never had the magic that the mono had. The mono was more in your face, so I didn’t bring it out in stereo.

Mettler: The stairwell echo you mentioned — is that what we’re hearing on “Any Way You Want It” during the “hey-ey-ey” at the end of the vocal line there, and the “stay-ay-ay” on “Glad All Over”?

But yes, that stairwell echo is on all the early ones — Do You Love Me,” “Glad All Over,” “Bits and Pieces,” “Any Way You Want It.” They were all the stairwell echo, yes.

Mettler: That’s like the special echo chambers Brian Wilson used out in Southern California on many of those Beach Boys classic tracks. You just couldn’t repeat it anywhere else. The other interesting thing to me in “Glad All Over” is, when the chorus is coming on, Mike sings the word “I’m,” and then you have the two drum beats before you sing “. . .glad all over” after it. Another deliberate choice to create the pause there before you sing the whole phrase?

Mettler: I also love the details on “Bits and Pieces,” like where we get to hear that crisp tambourine on the new vinyl.

Later on, we had a track called “Over and Over,” which went to No. 1 in the States [in 1965]. We did that in one or two takes. But when we got ready to overdub on it, the speed was wrong. I said to Adrian [Kerridge], our engineer, “I love the feel on this one, Adrian, but it’s very slow. It just needs to go up a bit.” He said, “I’ll just speed it up.” You can do that, but it will show. There was no varispeed in those days, so what we did was, we got a roll of Scotch tape, and just wound it ’round the capstan [i.e., the tape spindle]. We kept winding it ’round and playing it back until we got it up to the speed I liked.

The problem was it “waved” in the middle of the harmonica solo — but it sounded good! I never told anybody that — but the record got to No. 1.

Then I got a call from [legendary Wall of Sound producer] Phil Spector, who asked, “Dave, how did you get that sound with the harmonica?” And I said, “It was just our engineer, coming up with some gizmo.” But it was really just a 5-pence roll of Scotch tape! (laughs)

Mettler: That may be one of the most valuable rolls of Scotch tape there ever was! (both laugh) Were you all physically in the same room together in the studio in a similar setup like you were onstage?

Mettler: Having that live muscle memory before you went into the studio meant everybody knew where to do their thing. And just like you said, if you’re doing more than three takes, you play the feel right out of the song.

Mettler: What do you feel the lasting legacy is for The DC5?

I think we were very blessed, and I was very blessed. The five guys in The DC5, we were all mates before we made it, and to this day, we’ve never had a legal letter between us. We were all friends — and that’s rare, given what I’ve seen a number of my contemporaries go through.

Mettler: And you knew right when to leave — in 1970, when you were still on top. You knew exactly when to bow out. You cemented the DC5 legacy thing perfectly, I think.

We did what we believed in, and we did it for the fun of it. And there were never any hidden messages. We made our music to make you feel good.

But finally, the reissue wait is over, for The Dave Clark Five is now properly represented here in the 21st Century with the recently released collection simply dubbed All the Hits (BMG).

But finally, the reissue wait is over, for The Dave Clark Five is now properly represented here in the 21st Century with the recently released collection simply dubbed All the Hits (BMG).

Dave Clark: That was a trip for me, because it was the first time I had mixed or mastered for vinyl since, umm. . . (slight pause) wow, the ’70s. So, that was a real change. But, I mean, that’s what we all made it on in the ’60s — The DC5, The Beatles, everybody. It was all on vinyl.

Clark: Oh, it just happens. But I loved The Beatles. They were very innovative. And there was no rivalry. I did a documentary a few years back [in 2014]. I don’t know if you saw it, but it was on PBS in America, and on the BBC here.

Clark: So if you saw it, then you saw Paul [McCartney, of The Beatles] discussing that. He said it was good fun, you know — Liverpool vs. London.

Clark: Yeah, and because I’ve always been an independent, I always go in and master myself. I check the test pressing to make sure it’s right. And if not, then we redo it.

Clark: Yes, always, yes. Right from Day 1.

Clark: I never realized that in a million years. When we had The DC5, if we mixed with anybody who was 30 and over, we thought they were old! That’s what we were thinking then, anyway. (both chuckle)

Clark: Well, it was very easy. We had never worked in studios before. I would write songs with Mike [Smith, DC5 lead vocalist and keyboardist] or whatever, and I’d come up to what was then called Denmark Street in Tin Pan Alley [in London], to try to get somebody to record our songs. There was a place there called Regent Sounds that was quite famous, but there was only one-track, and they had the insides of egg boxes on the ceiling as the soundproofing.

Clark: For me, the most important thing was to get a live sound. The thing about recording in those days was that everything had to be perfect. But to me, it’s the imperfections that make perfection. Live sound is not like playing with a click track, like they started to do in the ’80s and into the ’90s.

Clark: (chuckles) Yeah. And that’s why our records were loud. But, I mean, that was the right way to do it for me. Many other people, if they’d had the freedom, would have done that too.

Clark: Yes, and that was because we were independent. When you work with people like — and no disrespect — Abbey Road and in-house engineers and producers, they were getting very little money, and they had to work by the rules if they wanted a job. So I do understand why, from their point of view. But as an artist, you’ve got to move with the times, you know?

Clark: Well, playing on the American [military] bases, there were 6,000 people — and they were great, because they were very appreciative. We had to play for 4 hours with a break in between. In the break between the two sets, they’d play these amazing records on the jukebox that we’d never heard of, and had never been released in England. They used to ask us, “Can you play them?” And I said, “Well, if you give us copies, then when we come back next week, we’ll play them.” That’s how we started covering “Do You Love Me” and “Twist and Shout.”

Clark: Yep! I mean, it’s strange, and it’s funny — when we did “Reelin’ and Rockin’” in the States, one of the guys in Cheap Trick asked me, “Did you write that?” And I said, “No, it was Chuck Berry.” He was an American icon, but he wasn’t as appreciated back in those days!

Clark: Oh no, I think that’s just the way we did it. We all wanted a different approach. In those days, it was all three guitars upfront, but I wanted a different approach with one guitar, sax, bass, drums, keyboards or piano, which Mike [Smith] played in those early days. I just wanted a different sound, you know?

Clark: The first record I ever bought was a 45 of his, “Blueberry Hill.” We couldn’t afford it, and my sister and I went 50-50 to buy it. (chuckles) [Fats Domino’s version of this perennially classic song was released in 1956.]

Clark: I heard it on the radio here. It was a song that was using sax, and that very much influenced me.

Clark: That’s right. On a lot of rock records, the vocal was way upfront, and the backings [i.e., the backing tracks] were way back down. But to me, the backings are as important as the vocals. And I couldn’t have asked for a better singer than Mike Smith, who was just amazing. [Smith passed away in 2008, at the age of 64.]

Clark: No, it didn’t come from a church background. It was just what we liked. There was no preconceived idea. I never thought it would happen like that, and take off like it did. We tried to be original, to be ourselves, in the production. To have the drums upfront was just unheard of, in those days — but I thought it was important. Well, for us, it was — making a different sound.

Clark: Oh, it’s amazing that you should say that, because when we first recorded that, it had the doubling up of Lenny’s [Lenny Davidson’s] guitar. I thought it never really came out on vinyl, maybe because of the equipment in those days.

Clark: To me, it’s a good yet a sore point in stereo, because the early records were all in mono. When you use four tracks, you can only really use three, because the fourth is the bounceback, or whatever they used it for. A couple of years later, stereo came in, and I wanted to go back and remix, for example, “Glad All Over” and “Bits and Pieces.”

Clark: It’s funny you say that — that’s one of the first things Bruce [Springsteen] got onto me about. It must have been in the ’70s. They wanted to know how I did that. He tried to repeat it [on the title track to 1975’s Born to Run]. They had recorded it two or three times, but he could never match what we did with that sound.

Clark: It was, yeah. When you do something live, like when we were performing in Tottenham Royal or wherever, that’s what you play. And when you go into the studio, you hear it back and you just improve it, or find whatever works in the studio.

Clark: I’ll tell you some things I’ve never told anyone before. (slight pause) The introduction to “Bits and Pieces” — those 8 [foot] stamps — actually, it was a mistake. The stamping was put on after. Ah, it was a long time ago, but it was supposed to be 6½ or 7 beats — or stamps, rather! (chuckles) But when it works, you just leave it. You can go and re-record it, but it’s never the same.

Clark: Yeah, we were all looking at one another. The drums were in the bottom corner, and we were all facing one another — but not like we were performing in the same one line. We needed some level of separation between everything. But yes, it was always done live, because I always wanted a live sound.

Clark: Right, because it becomes automatic then. And it wasn’t just me, it was the other four guys. They were all very talented. The thing about Mike Smith was, I knew Mike when he was about 14. He was a classically trained pianist. He could read music, and I couldn’t read music. We’d write a song, and play it in the studio. And then he’d say, “David! Technically, it’s wrong.” And I’d say, “Mike! To my ear, it sounds right.” And actually, the combination worked. Like I said earlier, if you play it by the book, it’s too perfect.

Clark: All these decades later — and this is feeling it for the first time, really — you realize what an impact we made. At the time it’s happening, you don’t really take it all in. And that’s not being modest; that’s being honest.

Clark: Well, I don’t know about that, but sure! (laughs) The main thing I had in mind was Muhammad Ali, who didn’t leave when he should have. It’s a shame he had to go on to do more fights because, in the end, you’re not the champ.

- Log in or register to post comments