The Cave of Forgotten 3D Dreams

While 3D makes immediate and perfect sense in certain contexts (games, horror), there have been a few dissenters as the revamped medium has slowly taken over big and small screens everywhere.

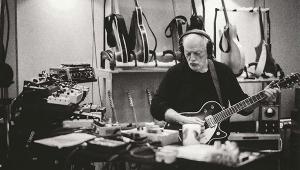

Leading film intellectuals from famed editor and sound designer Walter Murch to dean of critics Roger Ebert have weighed in against 3D filmmaking in recent years. Murch's opposition - based on principles of human evolution - seems difficlut to argue against. Ebert, on the other hand, is really to Hollywood's positioning of 3D as the default spectacle that'll keep audiences in theater seats for a few more years.

Ebert's thinking is that the technology isn't bad in itself - it just needs a reason for being. James Cameron's Avatar and his 2003 Titanic doc, Ghosts of the Abyss, gave the critic - who'd written that he "might become reconciled to 3-D if a director like Martin Scorsese ever used the format" - some hope, but this year his hero (and one of ours) may have met Ebert on his own terms.

Werner Herzog's Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a documentary look at the Paleolithic cave paintings at the Cave of Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc and the researchers who work in and around them (including "experimental archaeologist" Wulf Hein), was shot in 3D and done so on terms that might even make Walter Murch happy. Herzog's film makes the case that the essence of the human visual imagination, even some 30,000 years ago, has always been about three-dimensional representation.

The artworks - discovered only in 1994 and seen in person by very few human beings since, given concerns about preservation - are considered to be the oldest cave paintings known. They make extensive use of the topography of the cave walls to give shape to the creatures depicted - a charging bison, a curious horse - for which reason, as Herzog told the Paris Review, the film " had to be made in 3D." Given the fragile state of the paintings, Herzog feels, his film may be the only visual record to be made for some time, and thus has a duty to represent accurately the work of its Paleolithic artists - an accuracy that demands respect for their three-dimensional intent.

The Forgotten Dreams shoot took place under trying conditions - the four-man crew could only shoot for four hours per day, for six days, and were restricted to battery-powered LED panels for lighting. The tight spaces and limited schedule (there was no time allotted for scouting; Herzog had to shoot without on-site preparation) forced the director and his cinematographer, Peter Zeitlinger, to improvise both techniques and equipment for capturing the caves imagery, detailed in an amazing piece by Zeitlinger (search down the page for "Caves of Forgotten Dreams"). Synchronizing focus and aperture adjustments with a "belt built out of gaffer tape", mounting cameras upside down, and improvising mounting rigs for 3D cameras on location with magic arms were all in a day's work for the crew. Not quite a bison hunt, but far from your average series of expert interviews.

It's still in theaters (offical trailer here), so tear yourself away from MotorStorm Apocalypse and see 3D as your prehistoric ancestors intended.

- Michael Berk

- Log in or register to post comments