Horn of Plenty: Miles Davis

Clichés are truisms, Jack Kerouac once reasoned, and therefore true. But maybe not always - or at least not completely. One of the many clichés about Miles Davis is that beginning with cool in the late 1940s and ending with fusion 20 years later, he anticipated nearly every significant movement in jazz after be bop. This is generally offered as evidence of the trumpeter's restless nature, his habit of blazing a trail and then abandoning it once the crowd caught up with him. Yet bebop remained the common language of jazz throughout the two decades that Davis was regularly proposing alternatives to it. A better way of seeing him might be as a one-man lyrical fringe - an economical improviser who was rightly suspicious of be bop's overemphasis on chord changes but who never quite fit into any of the countermovements he helped start, all of which fell victim to their own excesses.

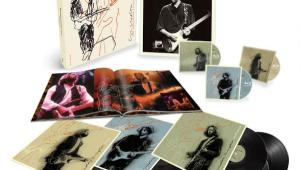

In any case, from his debut as an uncertain teenager with Charlie Parker in 1945 to his temporary retirement in 1975, Davis was a work in progress. And a raft of releases this year marking the 75th anniversary of his birth and the 10th anniversary of his death allows us to track his changes. (A boxed set focusing on the playful but too slick funk recordings he made for Warner Bros. after his 1981 comeback was unavailable at press time.)

The material from the end of the 1940s where Davis joined with Gil Evans and other arrangers to introduce delicate new shadings to modern jazz has been reissued numerous times. But the painstaking remastering for the Rudy Van Gelder Edition of Birth of the Cool (Capitol Jazz/Blue Note) allows us to follow the drift of the nine instruments (including tuba and French horn) as never before. Van Gel der has less to work with on the RVG Editions of Miles Davis, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (Blue Note), both from the early 1950s and featuring a strung-out Davis playing a nascent form of hard bop with directionless all-star bands.

- Log in or register to post comments