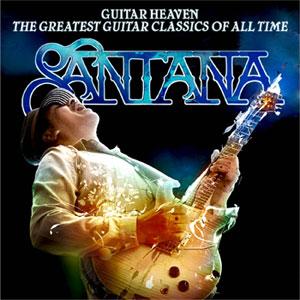

Interview: Carlos Santana

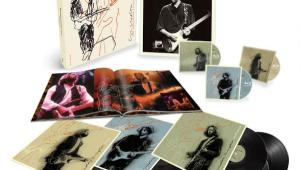

To borrow Mick Jagger’s growl from the Rolling Stones’ feisty Tattoo You track “Neighbours”: labels, labels, labels, labels, LABELS! People feel like they have to label just about everything, especially when it comes to music. So whenever I’m asked to describe what Carlos Santana’s music sounds like, my answer is quite simple: “It sounds like Carlos Santana.” In the case of the 63-year-old guitar guru, his name defines his sound. “The majority of the music I play is still African music,” Carlos explains. “I honor that. And it comes through the Delta, and Mississippi. I can play some tribal music for you that’s really a straight blues shuffle. I’ve yet to play polkas or Riverdance music, though.” And he lives very much in the present. As we sat together in a lofty Sony conference room in New York City this past July — the very same conference room where, just a few hours later, Carlos and record-industry magnate Clive Davis would film a joint interview that appears on the Deluxe CD+DVD Edition of the Santana band’s collaborative album, Guitar Heaven (Arista) — our first line of discussion was our mutual love of the iPad. And then we delved into the seeds that have borne this slice of Heaven.

Guitar Heaven is infused with your personal, spiritual connection to the material you chose to cover. Was that one of your goals?

I think my main goal was to honor the concept of trust. That’s the essence of a project like this. Clive Davis had the vision. He and I saw Rolling Stone’s list of “The 100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time” [in 2008], you know, and I thought, “Ooh, I don’t know if I want to do that — it’s kind of scary.”

I look at songs like women — there’s an Eric Clapton woman, a Jeff Beck woman, a Jimmy Page woman. But I started to honor Clive’s vision, and said to myself, “Well, look. ‘Black Magic Woman’ is Peter Green’s. ‘Evil Ways’ is Willie Bobo’s. [Bobo is a jazz percussionist who first recorded Clarence Henry’s song in 1968 on an album of the same name.] ‘Oye Como Va’ is Tito Puente’s.” But Clive said, “You’ve been doing those songs for a long time — they’re Carlos’s.” Then I said, “Yes, but these songs are like the Mona Lisa, so you date Mona Lisa.” You know? I often get asked, “Did you listen to the original songs? Did you get the same pedals, the same amplifiers?” I reply, “No, no, each song is like a woman. Why would I want to date the same woman wearing the same cologne and same suit as Eric Clapton?” This is not NASCAR, where you’re computing or comparing, where someone has to win and someone has to lose. This is about complementing. I trusted — and there’s that key word again — I trusted that Clive had enough clarity of vision to get the right producers, Matt Serletic and Howard Benson. But the most valuable players on this album would be my band, because they lay the foundation for all the different singers; that was essential to me.

How do you listen to music these days — vinyl albums, iPod, CDs. . .?

All of the above. Late, late at night, I listen to records on a turntable. I have many, many records, because that’s what I bought more than anything. When other people were buying cocaine and motorcycles and all that stuff with their first royalty check, I was buying a set of drums — and records. I wanted to learn how Elvin Jones, John Bonham, Mitch Mitchell, and Tony Williams did what they did. That way, I could tell my band, “Try this Al Jackson feel,” or “Try this Ringo feel.” I had to be able to point my musicians toward the feel of a song.

- Log in or register to post comments