JD Souther on the Legend of Longbranch/Pennywhistle

This is the true story of two 20th century American music pioneers — a pair of young and hungry desperados in the making who, in their mutual quest to become top-shelf modern-day songwriters, played no small role in forging the template for the then-burgeoning country rock genre.

In short, this is the ballad of Longbranch/Pennywhistle, the legendary 1969 collaboration between late Eagles co-founder Glenn Frey and his longstanding songwriting compadre, JD Souther. Found within the 10 tracks that comprise the self-titled Longbranch/Pennywhistle album are the secret sonic salve and song-construction building blocks upon which successive generations of singers and songwriters have drawn California-countrified inspiration, known or otherwise. Indelibly stamped songs like Frey’s cautionary jailbait tale “Run Boy, Run” and the tenderly sweet harmonies permeating “Rebecca” are juxtaposed alongside Souther’s yearning ode to the idealized yet calculating “Kite Woman” and the sociopolitical tsk-tsking of “Mister, Mister,” and they all helped sow the seeds for a style of music that’s loved universally far and wide to this very day.

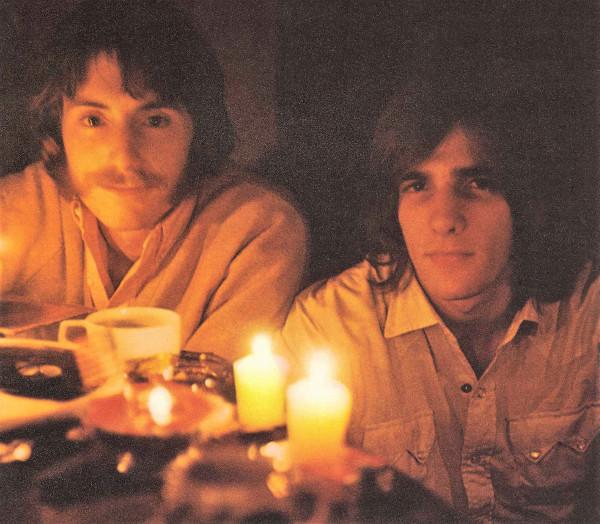

Ever the self-deprecating artist, Souther (at left next to Frey in the above vintage duo photo) is having none of that kind of genuflective talk, however — well, almost none. “I keep being referred to as an architect of something,” he acknowledges. “But I assure you, at the time, we didn’t think we were designing anything. We were just trying to make a living by writing songs.”

Long consigned to the cutout-bin tumbleweeds, Longbranch/Pennywhistle’s 10-track self-titled 1969 release on Jimmy Bowen’s Amos Records imprint finally gets its proper due via Geffen/UMe on 180-gram vinyl, CD, and download as remixed by producer/engineer Elliot Scheiner (Eagles, Steely Dan, Toto) and Souther. While Longbranch/Pennywhistle was formally made available on CD and via download back in May as a key component of Glenn Frey’s Above The Clouds: The Collection box set, it was only a matter of time before the album could re-bask in a spotlight all its own. Produced by Tom Thacker, Longbranch/Pennywhistle also boasts an impressive C.V. of top-tier collaborators including rockabilly guitar legend James Burton, slide maestro Ry Cooder (credited here as “Ryland P. Cooder”), pedal-steel legend Buddy Emmons, Wrecking Crew pianist Larry Knechtel, session drummer Jim Gordon, bass master Joe Osborn, and fiddle player nonpareil Doug Kershaw.

“It’s got a certain charm to it,” Souther demurs of the album with a wry chuckle, “even if it still sounds like an 8-track record from guys who didn’t write that well working with first-time producers.”

Souther, 72, and I got on the line to discuss the reissue’s sonic-restoration process, whether he thinks Longbranch/Pennywhistle pioneered the country rock movement, the origins of a truly unique band name, and the singular legacy of Glenn Frey (who passed away in January 2016). Run boy, run, you gotta move . . .

Mike Mettler: How satisfying is to you to have people experience, or even re-experience, the long-lost Longbranch/Pennywhistle record?

JD Souther: Very. When I heard the test pressing, it sounded pretty good to me. Elliot [Scheiner] did a pretty good job. I mean, he did what he could with it. It was a poorly recorded album to begin with. It was on 8 tracks, and they [i.e., the original label and producers] did some really weird things with it. Like, they locked the bass and the bass drum on the same track. And that was something we really couldn’t un-do, you know?

There was another dumb thing with two other instruments locked on the same track. But they didn’t have any idea what they were doing. We were only there for a few days with the producers. When Elliot went to mix it, he was like, “Man, I’m doing the best I can, but I think we just give it our best shot and play to historical accuracy here — it’s 1968. If we try to make it sound like an ’80s or ’90s or a modern record, it’s going to be cheesy, so let’s just go with what we have, and I’ll try to be as authentic as I can.” Even so, I think we each have one good song on the record.

Mettler: Let me guess. For you, it’s gotta be “Kite Woman,” since you also recut it for your first solo record [1972’s John David Souther], right?

Souther: Probably, yeah. Although “Mister, Mister” is a pretty good song too.

Mettler: There are a couple of interesting lines in “Mister, Mister,” especially when you listen to it now almost 50 years later. The line I’m thinking of is, “You say men are born in anger / to be cruel is to be strong.” You can’t help but think about #metoo when you listen to it today. Do you feel differently hearing a song like that now?

Souther: (slight pause) I feel like I was right.

Mettler: Isn’t that the thing about a great song? It’s going to have a shelf life beyond the moment you originally had the idea for it.

Souther: One hopes, yeah. There are some things in that song I was surprised I liked. I remembered it being sappier and a little more starry-eyed than I usually write. The first time it cued up after I really liked the mix and could just focus on the music, I felt, “Man, I was onto something then,” you know?

Mettler: Yes. It was one of your first “point of view” songs. You have your finger wagging at us, but you’re doing so with more of an observational tone, which set the table for where you were going as a writer. “Never Have Enough” has some of that too by the time we get to it at the end of the album, and so does “Star-Spangled Bus.”

Souther: Well, there’s a lot of finger-wagging in my songs on that album — an awful lot of finger-wagging! (both chuckle) It was 1968, and we were not happy with almost anything that was going on around us back then.

Mettler: “The more things change,” as the cliché goes. Now, I hate to be that guy, but I think it’s fair for me to ask the question of where this storied band name came from. Where did you get Longbranch/Pennywhistle?

Souther: We’d certainly never heard it anywhere before. We were just called John David & Glenn before that. We got a job, and we had a bass player then named David Jackson. He was a great bass player and piano player. This was right before our first big show, and the headliners were Cheech & Chong. Going on before them was Buffy St. Marie, and first up was us. We started talking about band names since there were three of us including David Jackson, and we didn’t want to call it John David & Glenn & David.

Mettler: It sounds like a law firm at that point.

Souther: Right! (chuckles) Maybe too much! A law firm of teenagers, all of them. But Glenn was really leaning towards anything Western. He’d been watching Poco and The Flying Burrito Brothers, and he wanted something Western.

What happened was, at the time, we were being managed by Doug Weston, [the owner] of The Troubadour. We were in Doug’s office and he said, “You gotta have a name.” I had been reading Mark Twain, so my head was all full of arcane language, phrases, and terminology. Glenn said, “Longbranch.” And I said, “Pennywhistle.”

Mettler: Just the first thing that popped in your heads, huh?

Souther: For both of us, yeah. Doug Weston said, “Great. They’re both phallic, so let’s use ’em both.” So, it just stuck. We said, “Yeah, okay, fine.”

Mettler: Was there any logistical decision to having a slash between the name on the cover for it to appear as Longbranch/Pennywhistle? Was that just a flourish put in there to make it look different, or was it something else?

Souther: It was there to begin with. I’m quite used to poetic slashes. It was just a way to separate those two words. (slight pause) It’s not a very interesting story. (chuckles)

Mettler: Oh, I don’t know about that, since I just learned something new about it. People have put so much weight on the Longbranch/Pennywhistle record, even without having heard it. You see it being listed as the very first country rock record, or the one that set things off. Do you feel the weight of that? Is that something you agree with?

Souther: I’m surprised at it, because we didn’t think we were the first. I’ll tell you who we thought the first country rock band was: It was Rick Nelson’s band. Rick Nelson was making country rock records when I was in junior high school, when he was on [The Adventures of] Ozzie and Harriet [a TV show that ran from 1952-66]. Every third or fourth show, they’d have this fake-y high school dance sort of thing at the end of the show, and Rick would sing whatever his new single was, whether it was “Waitin’ in School” (1958) or “Hello Mary Lou” (1961). And that was with guitarist James Burton — that was the crew, man! They made great country rock records.

Mettler: And James Burton, who also played with Elvis, is on your record too.

Souther: Of course he is! That’s one of the reasons, too, because we loved all of those records James played on.

Mettler: I know you like to downplay it, but I think Longbranch/Pennywhistle is a lot more clever than you maybe give it credit for being. It’s not a bad way to start.

Souther: Well, it just gives you some sort of foundation. You start out knowing there’s room for a few more chords, and a lot more voicings — just more ways to do things that are more than normally accepted in rock & roll. The first songs I heard growing up were all jazz songs and opera songs. My grandmother was an opera singer and my dad was a big-band singer, so that’s what I heard.

And then Glenn Frey brought some kind of steamroller, Midwestern rock & roll into my life as a songwriter. And, like me, he also loved Motown. He knew every Motown record by heart. But he also played with Bob Seger and was born in Detroit, so being part of that real Midwestern rock & roll scene meant he really understood it.

When I first met Glenn, I was still hanging out with these guys in the band I’d come out to California with from Texas, who had signed with Lee Hazlewood’s label [LHI]. They were called The Kitchen Cinq, a hopelessly cute name. I just didn’t want to be in their band, Mike.

Mettler: Not being in a band always seemed to be one of your things.

Souther: I’m not really a band guy, but I just didn’t feel connected to the songs they were singing and the music they were making, so I passed.

The guy who produced the Longbranch/Pennywhistle record, Tom Thacker, had been a DJ in Amarillo, and he came out west a little before me and my Texas bunch came out. He came with a country guy named Red Steagall, who still does cowboy camp country songs.

Tom Thacker had all these guys in The Kitchen Cinq, and he’s trying to think of ways to remake old rock & roll songs. He knew I liked this song by The Chiffons called “He’s So Fine” (1963). He was telling those guys he thought it would be a good remake as “She’s So Fine,” and I’m thinking, “Who gives a sh--,” you know? I don’t understand remakes anyway. If it’s a good song, leave it alone.

Glenn just pops into the room and starts singing it. but he sings it with that “Glenn Thing” — that curl at the end: “She’s so fiii-ine,” and he’s snapping his fingers. It was also a very Seger-like thing, and Tom Thacker went, “Yeah! That’s it!”

Then Glenn came back to where I was, and we continued working together on our songs. I thought, “Yeah, this guy has really got the groove in him. He’s really got that Midwestern rock & roll groove. It’s solid, it’s tight, and he knows what works. It’s simple, and he doesn’t over-sing it, and he doesn’t overplay it.” It was a real eye-opener as to just what ammunition he had onboard.

Mettler: Your two voices blended so well together — they always did, really.

Souther: Really well! But his voice was much better than mine — probably always was. Glenn sang softer than I did, and I sang further from the mike and louder, which means thinner.

Mettler: You’re way upfront in the mix. On Side 2, you also take centerstage.

Souther: Yeah. On Side 1, Glenn’s more up in the mix. It’s a little erratic, but we’re on the same mike, and we’re just fooling ourselves. We balanced it just like we would onstage, but eventually onstage we wound up singing on separate mikes, just because our guitars kept banging into each other. (MM laughs)

And I don’t think I sang very well on that album, except on “Mister, Mister.” I think it’s because it was so quiet on that song, that I wasn’t singing too loud.

Mettler: It reminds me a bit of Jesse Colin Young’s “Darkness, Darkness” (1969), and the way he handles the dynamics there.

Souther: Ooh, that’s one of my favorite records. I think one of the definitive records of the late ’60s is another song of his (half-sings): “Come on people, now, smile on your brother. . .” [That’s a line from The Youngbloods’ Young-sung “Get Together,” originally released in 1967 and later re-released in 1969, when it became a national Top 5 hit.]

That’s a magical record, man. When that record starts, the whole room lightens up. The first time I heard it in New York, I went, “Wow! This guy has tapped into something so beautiful, and so simple, and so elegant.” He had a gorgeous voice, and it does have that warmth. It’s just empathetic to everything.

Mettler: And now here we are, closing in on the almost 50-year mark of Longbranch/Pennywhistle. Is it easy to give it a broad-sweeping legacy statement about it from the surviving half of the creative team, or is that too much weight to put on you? (chuckles)

Souther: That’s too much weight! (chuckles) Well, I have one bit of advice: Don’t over-sing. If you have some confidence in your melody, just sing the melody.

I don’t have any critique of that album. I wish we had more time to do it, and do it with 16 tracks instead of 8, or even just have had a little bit better organization in the studio. That whole album was thrown together quick with no rehearsal, and was cut and mixed in 2 days.

That said, I think we did pretty well with it. We were just new at songwriting back then, and I think Glenn actually took more time with his songs than me. That’s why “Rebecca” and “Run Boy, Run” sound really complete, and concise. The two I took the most time with were “Kite Woman” and “Mister, Mister,” and those are the two that sound more mature to me and more complete, and less dependent on licks or flourishes.

Mettler: That’s some good detail-memory, JD, so there must be something special about the album that still sticks with you.

Souther: My memory is an ever-changing patchwork of pieces that don’t necessarily fit with each other. Sometimes it’s photographic, other times it’s completely . . . missing. (both laugh)

- Log in or register to post comments