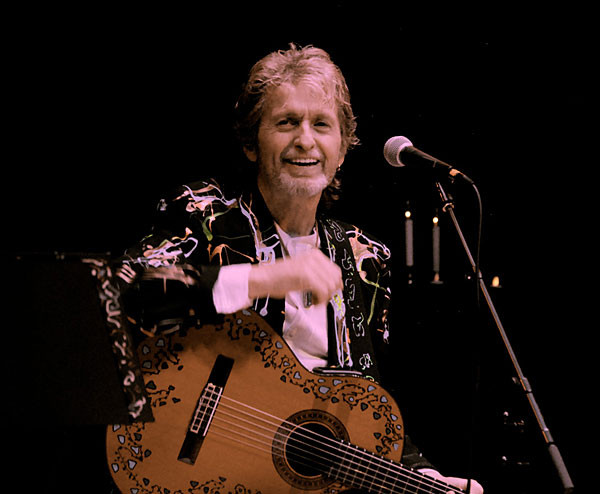

Mike, you did a great job with interviewing Jon. You have great knowledge and of Jon's musical legacy and how it flows. More unique is your insight into Jon's creative core. Often a reviewer hardly seems to not even be a music lover let alone connected to the artist's actual interests reflected in his/her catalog. I felt like I was eavesdropping on an animated pair of music lovers of which one happened to be a true progressive rock icon. Great stuff.

Jon Anderson, Soothsayer of Wonderous Stories Page 2

Anderson: (chuckles) Oh yeah, it's one of my favorites. People always ask me, Why did you get into doing Topographic?" Well, if there had never been Topographic [i.e., December 1973's Tales From Topographic Oceans], and there had never been [November 1974's] Relayer, there never would have been "Awaken." You were talking about mountains—well, "Awaken" is the top of the mountain for me.

Mettler: As it should be. I can also see the 1000 Hands song "Activate" as being a cousin of "Awaken," to some degree. Does that sound right to you?

Anderson: Well, sort of. I was quoting the lyrics from "Activate" to somebody yesterday. You would see these placards in everybody's garden or yard: "Proposition 33 — NO!" Or "Say No," or "Say Yes!" That's where that one came from, lyrically. But as a musical structure, it always came across as Yes in my mind, the kind of thing we'd get the band to do.

Before we had to lock ourselves up and stay indoors, I had been working on a long project of music that, to me, feels like the Yes music people want to hear. It won't be finished until next year, but we'll see what happens when people get a chance to hear it. It'll be fun.

Mettler: Are you able to tell me more about what that music sounds like? Or have I already heard some of it posted online?

Anderson: You have. You can actually go and listen to the blueprint on my YouTube channel, Jon Anderson Official. There's a series of them up there now—they're called "Hopefulness," "Joyfulness," "Thankfulness," and "Gratefulness." It's music I did in the space of one week, and then I ended up going on the tour with 1000 Hands. It's so funny—I came back afterwards [after the tour wrapped in late 2019], listened to all this music, and went, "Actually, it works, all together."

They're each about 20-25 minutes long, and now I've spent the last three months writing lyrics and songs and melodies within the framework of what you hear. It's all about Mother Earth. We're surrounded by this extraordinary experience of nature, and it's something we don't collectively rejoice enough in.

Mettler: Sounds like you're following your own 1000 Hands song-title directive of "Where Does Music Come From?" It kind of fits in with that concept, wouldn't you say?

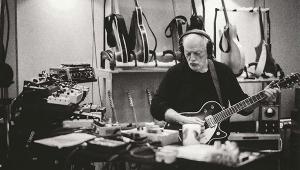

Anderson: Oh yeah, and I was just doing the video for that yesterday. I've got a green screen in my studio, and my wife was doing the filming on her iPhone. I was trying to remember how to sing it all, because there's a lot of vocalizations in it that I do. But it's something very, well, I don't know how to explain it—you make music two years ago, and now it's being heard by people. I think it's really good and it's a lot of fun, in more ways than one. And where does music come from anyway?

Mettler: Well, we all hear melodies and music in our heads all the time, and we can consciously think of songs in our heads. I'm sure you, as an inveterate melody writer and lyrical person, must have your own kind of radio station going on up there all day.

Anderson: All day long! And it's interesting to me how you could do it subconsciously, and that would be how you send an album to people: "Just send me a subconscious number, and I'll send you the album." "Ok!" You don't have it physically—you just hear it in your head every time you please.

What I've been trying to do is come up with movies these days. If you think about something like [David Lean's sprawling 1962 epic] Lawrence of Arabia—you know, I can "watch" the movie in my head because I remember it so well. There's a book out by Michio Kaku called The Future of the Mind [first published in 2014], and it explains that we're gonna get implants for where you can actually have better memory and better connection with other people subconsciously—and that you could actually close your eyes, and watch that movie. I think that's a good idea, actually.

Mettler: I think so too. I remember talking with Professor Kaku a few years ago when he was a consultant on the Nat Geo show MARS. I think we all need a mind reset anyway, the way things seem to be going in this universe. (chuckles)

[MM notes: Professor Michio Kaku, a noted futurist and physicist, was indeed a consultant on the Nat Geo show MARS. See ther "Is There Sound on Mars?" story posted here for more on that.]

Anderson: Yeah, when you think about the whole process of where we are—right now, the interesting thing to me is that the whole world is connected because of this virus.

Mettler: So true. Many artists and I have spoken about this open wave of creativity that's out there for anybody to access. You seem especially attuned to being able to channel anything you hear in any incarnation—and, in this case, we get a very worldly album out of you. There are so many fantastic styles on 1000 Hands. You really cover all 360 degrees of the globe, if you will.

Anderson: That's right! Like the vocalizing that I do in "Ramalama"—it comes from a video I watched. Actually, I did it on a track we [Yes] did years ago, called "We Have Heaven."

Mettler: Right, it's on [November 1971's] Fragile: "Tell the moon dog / Tell the march hare"—and then you keep repeating that with other phrases of yours going on behind it.

Anderson: Yes! And then I sang "Ramalama" after seeing pygmies do Burundi in these certain areas of Western Africa. The pygmies would go out hunting and foraging for food—and they sang all the time. It's amazing—the way they're singing is like the insects and what they hear from bugs, so you're getting, "dip di-do, daaah-dah, dip di-do daaah-dah, dip di-do, daaah-dah" (Anderson mouths the insect noises rhythmically, repeated three times), just like that.

I would get up every morning and do that, over the past three or four years. I've got so many different versions of that kind of idea. And a), it's very relaxing, and b), it's very good exercise to sing every morning—and sing well.

Mettler: Would you say that even some of the vocalizations you did inside [Close to the Edge's] "Siberian Khatru" follow in the same way—as in, the cadence with which you sing the single words and idea clusters in the back half?

Anderson: Yeah, I would! Back in those days, somebody gave me an EP of the Ramayana monkey chant from Bali. It really blew my mind! (laughs) There's so much music out there, and even now, well (sings), "Even Siberia goes through the motions." Crazy times we're living in.

Mettler: See how far ahead you were? You sang that line just now, and we're still connected to those concepts. And if you don't mind, I'd like to ask you about working with Vangelis [the Greek keyboard/synth maestro best known for his April 1981 Chariots of Fire soundtrack]. You almost had Vangelis play in Yes, isn't that right? You brought him around when Rick Wakeman left the band for the first time [in June 1974].

Anderson: Yeah! Meeting Vangelis was a trip. He just didn't think electric guitar was a real instrument—that's what he said to Steve [Howe, iconoclast Yes guitarist]. "It's a good instrument, but not a real instrument." I was like, "Uhh, we're trying to make friends here. That's not the first thing to say."

Mettler: Not the best way to start, but at least we got some great collaborations between the two of you later on as Jon & Vangelis. And I would say [July 1981's] The Friends of Mr. Cairo would be perfect for a surround sound visitation, especially the title song. That's another thing you can give Steven Wilson to do.

Anderson: I agree! Well, I'm going to do up to two surround releases next year, so maybe we will! I knew what I was going through when I was doing that music, but then you listen to it years later and you go (incredulously), "How did I do all that stuff?"

[MM notes: The storyline of the 12-minute title track for The Friends of Mr. Cairo was essentially based on the October 1941 movie version of The Maltese Falcon, with voiceover actors doing the Peter Lorre, Sidney Greenstreet, and Humphrey Bogart-inspired dialog. Quincy Jones once told Anderson that The Friends of Mr. Cairo song "State of Independence," as covered by Donna Summer in July 1982, may very well have influenced the Michael Jackson/Lionel Richie-penned March 1985 charity song "We Are the World," but that's a story for another time.]

Mettler: Finally, we should wrap things up by talking about "Now," which is an important concept that appears in three permutations on the album. You have "Now" at the beginning, "Now Variations" in the middle, and, at the very end, "Now and Again," where you and Steve Howe come together for the first time in a long time.

Anderson: A long time—like, almost 20 years, or more. I'd be in touch with Steve now and again, and I always say, "Hey, Steve, if you've got a piece of music you'd like me to sing, please send it." He's not inclined to do that, so you say, "Ok, it'll happen when it happens." That's my mantra.

Mettler: The lyrics you have in "Now and Again"—were they tailored specifically for Steve, when it comes to the "brother" concept? Did you feel he was the only one who could work on it? Was it that specific?

Anderson: Originally, "Now" was just a three-minute piece, and then I thought it should be split up into three sections. The last section could be called "Now and Again," and we could extend the music a bit. When I heard what Michael Franklin, the producer, had done, I felt it needed a guitar. And since I sang on Steve Howe's album when he did Bob Dylan songs [July 1999's Portraits of Bob Dylan]—I sang "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands," which I love—I always thought, "He owes me one," you know? (both laugh)

So he said, "Yeah, I'll do it." And when I heard it—when I heard his playing—I had to sing something. I thought about our experiences together, and how it was so many years ago. And in the world, we'll always be brothers.

Mettler: That's a nice way of putting it. And if there's ever a "Re-Yes" where everyone gets together again, we wouldn't say no. And speaking of that word Yes, which speaks to the positivity of life—when you guys chose that word as the band name, that always seemed to be the right call and right vibe, don't you think?

Anderson: Very much so! And you know the story—originally, it was Chris [Squire's] band, and it was called Mabel Greer's Toyshop. And I said, "We've gotta get a shorter name." Chris said, "Well, why don't we call it World?" And of course, [original Yes guitarist] Peter Banks said, "No—call it Yes!" And we said, "The Yes?" "No no no—just Yes!" And that stuck. You don't think about it, really: "Oh boy, that's good!" (chuckles)

Mettler: You don't think about it becoming an infamous logo by Roger Dean that's still recognizable 50-something years later. And, like I said, you're always positive. What's the secret of you being positive 24 hours a day, Jon? The world needs to know.

Anderson: Well, I'm in love with my life. I love my children and I've got a lovely wife, and some friends—well, not so many. I love life, and I love what I do. And the thing is, every morning I wake up, I'm excited to go into the studio, because I'm getting better at my job.

Mettler: Isn't that a good point to make that, at age 75, you're as vital creatively as ever. You'll probably outlive us all.

Anderson: (chuckles heartily) I always think I'll be about 103, so I've got 20-some years left.

Mettler: Well, we're gonna be there every step of the way. I mean, why stop there? Let's see how far we can go. We've got a lot to do.

Anderson: It's interesting that we're talking about this. You learn music because you're alive. You make music because you can. You don't make music to make money—you make music because you can, and because you're alive. You try to get a record company to get people to hear your album, but sometimes, it's not even gonna happen. You just gotta say, "Ok, it'll happen when it happens." If people want to find this album, they will.

- Log in or register to post comments

Great interview, Mike. I wasn't aware of a lot of Jon's collaborations. Now I've got some new music to look forward to!