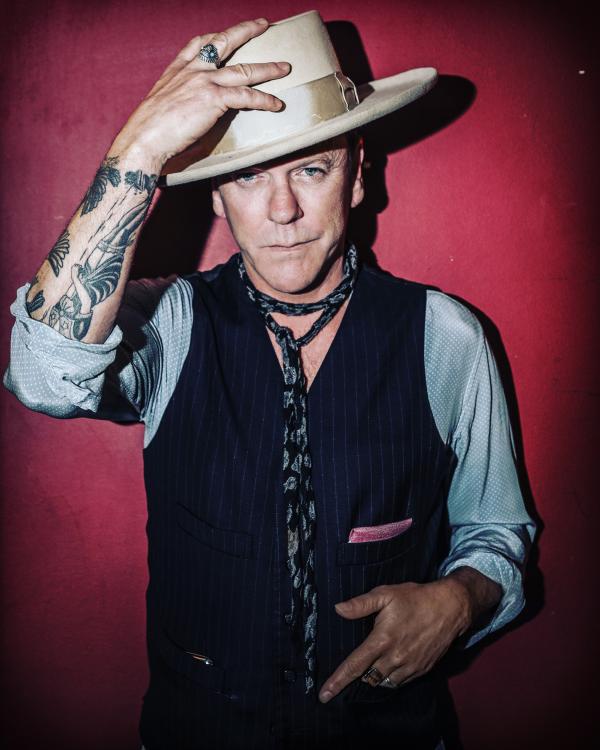

Kiefer Sutherland Plays It Reckless & Free

When it comes to creating and playing original music, one thing you should never call Kiefer Sutherland is Johnny Guitar-Come-Lately.

While it’s quite true Sutherland is best known for his portrayal of the iconic, star-crossed rebel CTU agent Jack Bauer for over a decade on the serial real-time spy thriller 24 (the show many could argue as being the catalyst for the binge-watching phenomenon) in addition to his current incarnation as President Tom Kirkman on Designated Survivor (which will be streaming its entire third season on Netflix starting June 7), his music chops actually run quite deep. In fact, they extend all the way back to when he first picked up a violin at age four — a move that not only led to his first acting job, but also planted the seed for getting his hands on his first acoustic guitar.

“I wanted a guitar since I was about seven,” Sutherland confirms. “And my mom [Canadian actress Shirley Douglas] said, ‘Well, if you play the violin until you’re about 10 and you do all of the work, I’ll get you a guitar.’ And she was true to her word. She got me a guitar, and I don’t think I ever picked up the violin again!”

From there, Sutherland played guitar every chance he got, but it wasn’t until he teamed up with his best friend, songwriter/producer Jude Cole (Lifehouse, Rocco DeLuca & The Burden, Lindsay Pagano), that his innate songwriting talent truly began to bloom.

Initially, Sutherland and Cole wrote songs together that the pair would send to music publishers for other artists to record, until Cole put his foot down and told Sutherland he should just cut them all himself. This begat Sutherland’s well-received August 2016 Ironworks debut Down in a Hole, which has recently been followed up by his even-more impactful sophomore effort Reckless & Me, released by BMG in late April 2019. Powerfully personal gutbucket songs like “Open Road,” “Blame It on Your Heart,” and “This Is How It’s Done” all serve to illustrate Sutherland’s burgeoning ability to connect with audiences on a deeper level than even he initially expected. “I have found that being able to write through some of the difficult times or experiences, or even some of the more beautiful times and experiences, helps you gain a kind of perspective,” Sutherland admits. “And because I never had a diary, these songs were the best way for me to do that.”

Initially, Sutherland and Cole wrote songs together that the pair would send to music publishers for other artists to record, until Cole put his foot down and told Sutherland he should just cut them all himself. This begat Sutherland’s well-received August 2016 Ironworks debut Down in a Hole, which has recently been followed up by his even-more impactful sophomore effort Reckless & Me, released by BMG in late April 2019. Powerfully personal gutbucket songs like “Open Road,” “Blame It on Your Heart,” and “This Is How It’s Done” all serve to illustrate Sutherland’s burgeoning ability to connect with audiences on a deeper level than even he initially expected. “I have found that being able to write through some of the difficult times or experiences, or even some of the more beautiful times and experiences, helps you gain a kind of perspective,” Sutherland admits. “And because I never had a diary, these songs were the best way for me to do that.”

Sutherland, 52, called me from his Southern California homebase before heading out to a band rehearsal to discuss his songwriting process and love of vinyl, how playing music live has informed his subsequent acting choices, and what kind of music Jack Bauer and Tom Kirkman might have on their personal playlists. Maybe someday you’ll find what you’re looking for down that open road. . .

Mike Mettler: My feeling is that you and Jude Cole have quite a good shorthand together whenever you’re talking about your mutual production goals. I mean, you guys know exactly what the vibe and tone should be and the kind of sound you’re going for, right?

Kiefer Sutherland: We do, but I have to be honest. Jude is an incredible producer, and his knowledge is much more vast than mine. The way that it makes sense for us is, I’ll come to him with a song, and then we’ll work on that song together. He might not like a line in the bridge, or something like that, so we’ll get it to a place where we’re both really excited about the song. I’ll be there on an acoustic guitar, and he has such beautiful ears. He instinctively knows what to do, and then he goes for it.

Only on a couple of songs did he go in another direction, but then he’ll always say it first: “I’m not happy with where this is at.” And the one thing we always go back to — or at least, I will, because I was a huge fan of the kind of warmth of The Band on their early-’70s records — is, if we ever got lost, we would take something back to a basic kind of arrangement, and then Jude would find it. He would figure out what we wanted to do. Jude is in charge of that aspect of the record-making. My responsibility was to come up with 10 or 15 songs that work together.

Mettler: Yeah, you guys really thread a good story here. I’m really excited that we got Reckless & Me on vinyl, because I have Down in a Hole on wax, and I feel vinyl is the best way to listen to the music you guys make together.

Sutherland: Oh, bless your heart. Chris Lord-Alge [Prince, Joe Cocker, Green Day] mixed the album, and he did the same for the vinyl. We’re really excited about that too.

Mettler: We’re just about the same age, so I have to imagine vinyl was a very important thing for you growing up.

Sutherland: It still is, and I’m looking at the stereo I’ve got in my house right now. To get my record collection digitized, or into the ways kids listen to music today — it would just take too much time. (MM chuckles) There’s just something so nice about being involved in the way you’re listening to a record — getting up to turn it over, putting the needle on it — just to hear the cracks. The organic composition of a record and the act of using a needle — it just adds something to it.

I remember watching television one day, when HD had just come in. HD is fantastic for sports — and some would say it was made for it — but I remember I was watching [1969’s] Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, and it looked like it was on videotape, because all of the extra light. All the things that film is responsible for gets lost in that. I liken that to my experience with my albums.

Mettler: I think you need a certain level of grit in the groove, to get to that kind of honesty.

Sutherland: I agree.

Mettler: Are there touchstone vinyl records for you — ones you put on regularly, or ones that stick with you as an artist?

Sutherland: For a variety of reasons, yes. For example, Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline (1969), Jackson Browne’s Running on Empty (1977), Jackson Browne’s first record [1972’s Jackson Browne], or even The Band’s greatest hits album [1978’s Anthology] or Van Morrison records — there’s a warmth to those albums on vinyl that I just don’t experience in any other format. Having said that, I can put on Supertramp’s Crime of the Century (1974) — and I have a very good speaker system (chuckles) — and it will move your hair back. You can hear everything going on in those records on the vinyl tracks. It’s just astounding. I felt that way, very strongly, when we went to CDs back in the ’80s. I missed the vinyl.

Mettler: What kind of gear do you have? You’ve gotta have a good system cooking there.

Sutherland: I’ll have to walk up to it and tell you, because I just wandered outside. Let me put my glasses on. I’m very happy with it. My turntable is a Marantz, and my amplifier is a Marantz as well. The speakers that I’m very impressed with are my Martin-Logans. It’s the best-sounding system I’ve had in my lifetime, and it’s really that simple. But I’ve never gotten past [a volume level of] seven without my neighbors coming out onto the lawn. (both chuckle)

Mettler: That probably happens if you ever put something on with serious bass content. Now, I happen to think you’ve established yourself as a really good, first-person songwriter. When I heard that line, “Shot a man in Laredo” in the song “Agave,” that was clearly your wink to a Johnny Cash kind of vibe [a reference to the line, “But I shot a man in Reno / Just to watch him die,” from 1955’s “Folsom Prison Blues”]. You’re really able to embody that kind of character as a songwriter.

Sutherland: Yeah, well, thank you very much. Obviously, I haven’t shot a man in Laredo — or certainly not that I’m going to confess to (MM laughs) — but most of the songs on the record, whether it’s “Saskatchewan” or “Song for a Daughter,” are based on really personal experiences in my life. For me, that kind of first-person narrative, and expressing that kind of personal experience, has been a godsend, which is why I’ve been able to keep doing it. It just took me a long time to gain the kind of confidence to climb the mountain — and I completely blame Jude for that. (both chuckle)

Mettler: And it only took you a couple of years to get around to doing it that way, right?

Sutherland: Well, maybe about 20. I had no intention of making the first album [Down in a Hole]. We were writing and recording songs and sending them to BMI and Sony to see if any other artists would be interested in doing them, and it was Jude who said, “I love these songs and they’re clearly yours, so I think you should do them.” I wasn’t very confident about that idea, but he knew me well enough. He took me to a bar and got me kind of drunk, and all of a sudden, it sounded like a better idea. By the end of it, I really liked the way they sounded too, and took the jump forward.

Mettler: On both albums, the character of your throat voice, as I call it, really comes through quite naturally. It sounds to me like you’re cutting things to tape and you’re recording in the same room, looking at each other.

Sutherland: We are, in fact — and on Down in a Hole specifically, Brian MacLeod was on drums, Jude was on bass, and I had an acoustic guitar. But because I was also doing vocals and the studio was so small — we were doing it at Jude’s place [The Ranch] in Box Canyon [in California] — I ended up standing in a small, little field in the middle of the night while I was singing (chuckles), so that way my vocal wasn’t going to get interrupted by their drums. We recorded like that a lot.

Mettler: That’s literally the way Paul Rodgers and Bad Company recorded his vocals for their first album [Bad Company, released in June 1974]. He was standing out in the field at the castle studio they were at while he sang the vocals for the song “Bad Company” [in November 1973, at the onetime three-story poorhouse known as Headley Grange in East Hampshire, England].

Sutherland: Oh really? That’s very funny. That was about the same for me. I don’t know what Paul Rodgers’ experience was like, but it was f---ing cold! (both chuckle) But we had a lot of fun doing that.

Mettler: Doing the vocals like that just gives it a more “real” kind of flavor, and there’s a natural character to your vocal that comes across with maybe just a light touch of reverb here and there — but not that much. I mean, you were conscious of sounding as real as you could, right?

Sutherland: We leave the track dry. What Jude might do to an overall track at the end is never specifically about the vocals. Those are recorded dry.

Mettler: There’s also a lot of good stereo soundfield play. A guitar line will come in on the right side, and then a nice, cool organ fill comes in behind it, or a tambourine sound that’s really crisp on the other side — it all makes me want to hear this on wax even more.

Sutherland: That’s really a product of Jude Cole and Chris Lord-Alge. Talk about two guys who have a shorthand! They’ve been working together on and off for 20 years. Watching Jude record a record, and then watching the two of them mix it, is like theater. It’s pretty awesome.

Mettler: Would you say some of the fingerings and voicings you learned on the violin as a kid was something you could transfer over to how you approached a guitar neck, as opposed to learning piano where you’d have to switch up the chords much differently?

Mettler: Playing live has become a core passion of yours, and you’ve got another big tour coming up fairly soon. What is it about playing live that appeals to you the most?

The thing I had not counted on was how much I love the touring. And when trying to figure out a common denominator between what I love about acting and what I love about music, it becomes very simple: It’s the storytelling. And that can be the storytelling before you even play the song. “This is where I was at when I wrote it. This is why I wrote it. This is what I was going through, and maybe you’ve gone through something like this too, and if you have, this song is for you, to remind both of us that we’re not alone in trying to get through this thing called life — which, by the way, is not easy.”

Mettler: No, it’s not. That’s very true.

Once I adjusted to that, and kind of leaned into it and embraced it, I found the response from the audience was incredibly generous, and I was moved by that.

Mettler: And that’s immediate. You’re looking into people’s eyes, reacting to you speaking about yourself, and that’s a heavy thing to handle if you’re not used to it.

Mettler: And it’s okay to share that kind of experience with people, as hard as it may be to do so.

And so, it’s a combination of that, and the shared excitement. I’ve done a lot of theater in my life, and there are rules in the theater. You’re supposed to sit and be quiet, and show your appreciation at the end of the performance. Whereas at a music show, you want to get people up and out of their seat. You want ’em moving, and you want ’em screaming. You wanna get ’em riled up and excited. It’s a visceral kind of experience. I just did not count on the degree that I would fall in love with it — and I really did.

Mettler: That’s why I like going on the road for an extended period of time and being in the middle of what that experience is from night to night — to connect you with something that takes you out of the daily thing and onto that separate plane of connection. I know you, as a performer, understand exactly what that means.

Mettler: That’s another reason why I like seeing tours over an extended period. You get to see the subtle changes night after night. Maybe there’s a chord you’ve switched up, or you vamp a little differently, or as the singer, in the moment, you’re adding that little something extra to a turn of a phrase.

The audience has a lot to do with that — and also the adaptability. Some audiences are loud, and some are quiet. Some don’t speak the language, you know, and you’ve gotta adapt to that. And those are all really interesting and exciting challenges.

Mettler: Would you say that’s informed your acting, in reverse? Maybe you’ve been able to show a different face, or. . .?

Mettler: We’ve watched you through all cycles of 24, and we’ve also watched the subtleties of you playing Tom Kirkland as you’ve had to go through more human things over a longer scale of time. We’ve seen you react to those situations and have us connect to that differently, so I figured there must have been something that triggered all that. That you went, “Oh, I can show a little more of me here, as opposed to just playing a character.”

Mettler: Correct me if I’m wrong, but wasn’t there an episode in one of the early seasons where Tom made reference to liking James Taylor, or something like that?

Mettler: That leads into a two-part question I have, then. First, what would you, Kiefer, have Tom listen to, if he actually ever had time or a moment to himself to relax with music?

Mettler: I’d say Gordon Lightfoot might fit in there, or even Randy Newman, or Tom Waits.

Mettler: Yeah yeah, and I think Gordon’s “Canadian Railroad Trilogy” would fit in there, since Tom is a history buff [and a former history professor]. Secondly, what would Jack Bauer have listened to? Or would he have even had the time to ever relax? (chuckles)

Mettler: . . .And Justice for All (1988) fits perfectly with Jack, I think. I know Vietnam was a little bit before his era, but The Doors were very big for a lot of military guys during that time, and I think that carries over from generation to generation.

Sutherland: Yeah, and very much so. The violin also forced you to have some semblance of an ear, because you didn’t have frets, and you really had to know where you were on the neck of your instrument. When you transpose that to a guitar, especially when you’re 10 or 11 years old, that is

Sutherland: It was the experience I hadn’t counted on. The one thing I loved about making the records was, you know, Jude’s my best friend, and we haven’t had a lot of time to spend together because I travel to do my work, and he’s busy doing other things since he’s got Lifehouse and other bands he’s taking care of. This was a great opportunity for us to spend some time together doing something we’re deeply passionate about and in love with, which is music, so I love making the records.

Sutherland: So, we have these kinds of moments, and you get to play the song. And then you realize, “Wow.” The real difference here is, I had a real amazing time doing 24, and it was a decade of my life. But I was playing a character, and by no stretch of the imagination am I Jack Bauer. All of a sudden, I’m onstage, and for the first time in my life, I’m playing songs that are very personal, something I’ve spent most of my life trying to protect, and there was no character separating myself from an audience.

Sutherland: Yeah, and realizing their response is, they’ve gone through a similar thing. You know, I’ll be the first to tell you, I’m the luckiest person I know. But it doesn’t mean I’m going to get through this life without someone else passing away that I’ve loved, and it doesn’t mean I’m not going to get my heart broken. There are basic certain things that, I don’t care how lucky you are, we all have to go through.

Sutherland: When people realize they’re not alone in going through something, it somehow makes it better. It doesn’t take it away, but you just (slight pause) . . . you don’t feel alone. I think that’s really important.

Sutherland: I sure do, and the high that you get when you feel that you and your band have put forth not even your best effort, but an effort that was better than just a few nights before. For whatever reason, the excitement of that is thrilling, like nothing I’ve ever experienced.

Sutherland: Or everybody that night is just exceptionally tight. People are watching and listening to each other, and there’s a connection with the band on this given night that just was special.

Sutherland: It did, actually! That’s a really smart question — and very interesting that you brought that up, because I’ve told that to a couple of friends of mine. But no one has ever asked me, so I’ve never brought it up. In a show like Designated Survivor, I’ve felt a little more comfortable bringing that character [President Tom Kirkman] a little more closer to me as a person. And that is a direct result of feeling more comfortable onstage, being myself.

Sutherland: The character is always going to be responsible for the circumstances that are driven by the plot, but how you choose to shape that character, for me, became more personal — and that was a direct result, as you said, of finding this more personal experience with an audience on a very, very personal level.

Sutherland: I might have done that, yeah. I think they [the writers/producers] would have asked me about that, and Tom Kirkman would definitely have been a James Taylor fan! (chuckles heartily)

Sutherland: I was always interested in the fact that [former U.K. Prime Minister] Tony Blair was a guitar player, and [former U.S. President] Bill Clinton was a sax player. At some point, they were all teenagers who went to college, and they would have been impacted by their times. James Taylor and Jackson Browne would have been really good fits for Tom, and so would Jim Croce. But I also think Tom Kirkman, in his early teens through his early 20s, was listening to everything from Pink Floyd to AC/DC, because he couldn’t have avoided it. I also think he would have listened to artists like Joan Armatrading or Tracy Chapman, in displaying his political side.

Sutherland: Gordon Lightfoot would absolutely fit in there — especially if he [Tom] took a summer trip to Canada!

Sutherland: Um, I think when he was younger, he would have, given the age range, been listening to similar stuff. I find that most of the guys like Jack Bauer who spent time in the military and were working out as hard as they had to work out and had to find the stuff that drives them, I’m sure that Jack Bauer would have been a Metallica fan — or at least in his younger years. When people are that physical, they tend to listen to something that drives them. It’s a really interesting question.

Sutherland: And that’s such an interesting thing too, because The Doors, they had multiple writers in that band. The Doors could write a pop song, and then they could write a jam-band song. I think that combination was kind of perfect — not just the lyrical content from [singer] Jim Morrison and what he was writing about, but that, in combination with that Ray Manzarek keyboard sound, it just seemed to work perfect for defining that era. And very much, as you’ve pointed out, for defining the counterculture within the armed services during Vietnam, which most of them thought was a f---ed war. They were a perfect representation of that.

- Log in or register to post comments