Since the Blu-ray only offers the core album in high resolution audio, I combined my purchase with the 24-bit/96-kHz download from hdtracks.com. (It's currently on sale at 20% off and is also available in 24/192) Not something I normally do, but this album is worth it. The Atmos mix is easily one of the best I've ever heard. It's a shame the entire album wasn't done. The article was a great read. I had no idea so many great artists were involved.

The Making of All Things Must Pass

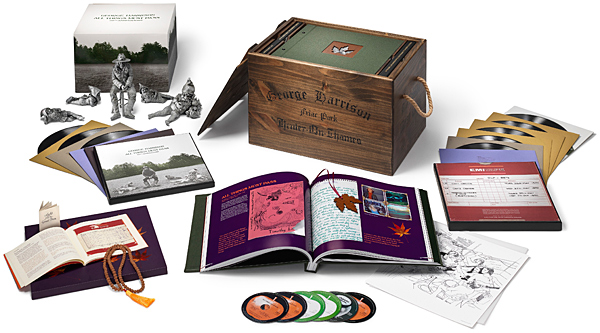

Its 50th anniversary is now being feted with a suite of new special editions, which include a brand-new remix from the original multitrack tapes by Grammy-winning engineer Paul Hicks and executive-produced by George's son, Dhani Harrison. The special editions feature everything from 2-CD sets to 5-disc sets (as well as multiple-disc vinyl pressings) containing not only Hicks's new remixes, but George's demos (described below), outtakes, and a Blu-ray disc with 5.1 surround and Dolby Atmos mixes. There's even an "Uber Deluxe" set packaged in a beautifully crafted wooden crate containing all of the vinyl and CD/Blu-ray sets plus an All Things Must Pass scrapbook curated by Olivia Harrison (which also appears in other deluxe sets) with George's lyrics, tape box images, and more. The Uber set also includes a "Making of All Things Must Pass" volume, a set of replica garden gnomes (as featured on the LP's cover), and a limited-edition lithograph by bassist Klaus Voormann, who played on the album. (For details, visit georgeharrison.com.)

George had previously released two other albums on the group's label, Apple – a soundtrack LP, Wonderwall Music, in November 1968, and an experimental disc, Electronic Sound, in May 1969. But this was the first to feature Harrison's wonderful song compositions, 17 in all, along with a bonus disc of jams, recorded mostly during the sessions, Apple Jam.

The first step in the process, of course, involved finding appropriate players to accompany him on the new recordings. The previous December, Harrison had joined American R & B rockers, Delaney & Bonnie Bramlett, who were touring Europe with an all-star backing band. The group included, among others, Eric Clapton, session players, drummer Jim Gordon and bassist Carl Radle and Hammond organ player Bobby Whitlock, as well as sax player Bobby Keys and horn player Jim Price. The first four, of course, would, the following year, become Derek & The Dominos.

"Delaney & Bonnie and Friends was a rowdy bunch," Whitlock recalls. "But the instant George walked on the bus, he brought an air of peace with him. He had this presence – you could feel it, even before he got on the bus – you could feel him coming."

The European tour wrapped up in Stockholm on Dec. 13, Whitlock continued touring with them in the States through February, before finishing. At guitarist Steve Cropper's suggestion, he flew to England (courtesy of a plane ticket from Cropper), and called Clapton, setting up camp at the guitarist's Hurtwood Edge estate. The two became fast friends, playing and writing together. Then, one afternoon, he says, "George called and said he wanted us to put a band together, to be the core band for his new album he was about to record."

Whitlock first contacted legendary session drummer Jim Keltner—who would shortly become a mainstay of not only Harrison's, but Lennon's and Starr's recordings—but the drummer was unavailable, due to a commitment on sessions for Gábor Szabó in the States. For now, it would just be Clapton and Whitlock, for whom Harrison came to Hurtwood and played the pair his songs on an acoustic guitar.

The other part of the core band came in the form – of course – of Ringo Starr and another person who would become a common fixture, again, on Harrison's, Starr's and Lennon's albums of the 70s, bassist Klaus Voormann. Voormann had been one of The Beatles' early friends from their days in Hamburg, and went on to design the cover of their 1966 LP, Revolver, as well as joining Manfred Mann that same year, playing bass.

He was always close with George. "In 1967, I had an apartment in Raynes Park, near Wimbledon, where I had a harmonium," an organ operated by pumping foot pedals. "He wrote 'Within You Without You' on that harmonium, playing, while I pumped the pedals and recorded him on my tape recorder."

While Klaus had never played bass with any of the Fabs ["Well, when they were at The Top 10 Club in Hamburg, I played bass on a few songs – I had no idea what I was doing"], upon leaving Manfred Mann in 1969, John asked him to play with Clapton and drummer Alan White at the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival Festival in September 1969 (eventually released as Live Peace in Toronto 1969), and subsequently record the second Plastic Ono Band single with John, "Cold Turkey," a few weeks later – his first recordings with both Lennon and Starr.

"Playing with Ringo is very easy – because he's so good," the bassist explains. "Sometimes, you have drummers who speed up or listen too much to what you play. They copy what you do – and Ringo wouldn't do that. He listens to everything and takes it in. He doesn't show off – he just plays what's needed for the song. And that's what I do, too."

In early Spring, Harrison asked Voormann to play on the sessions for his new album. "George was still living in Esher," he recalls of Harrison's first home, where he lived with his wife, Pattie, before moving, on March 12, to his giant Friar Park estate in Henley. "I went there a few times, and we jammed together on guitars here and there. He knew I could play, but I think he was trying me out a little." As with the Dominos, Harrison played his friend his new songs. "They were wonderful. And after he moved to Friar Park, I stayed there, coming in with him to the studio, going out together. I had the greatest time in my life."

A second drummer, Alan White, would also play on the sessions, at least for the first week. White had already appeared with John, Eric and Klaus the previous fall in Toronto, as well as in January with George on John's "Instant Karma!" recording.

One other key player was arranger John Barham, who had met George at Esher in 1966, when Ravi Shankar came to play for him there. Barham had subsequently worked on Wonderwall Music, and, on March 10, 1970, had created an arrangement for an unreleased session George helmed at Trident for a project by Indian musician Aashish Khan (which also featured Eric, Klaus and Ringo). A month later, around April 1970, he was dining with the Harrisons at Friar Park on a Saturday evening, when George, without introduction, began playing his new songs on an acoustic guitar. "At that time, I had no idea about George's plans to record an album of his own songs, and no idea that he wanted me to arrange strings for it," the arranger recalls. "I made suggestions about string arrangements for some songs. In retrospect, I assumed that George had decided to ask me to come over and listen to his songs to judge my response to them." He would eventually attend most of the sessions for the album, to allow himself to get familiar with the tone of each of the recordings, in person.

Harrison remained busy with Apple Records artists up until his own sessions began, producing two new albums, for beloved background singer Doris Troy and for uber-talented keyboardist Billy Preston. He would invite the latter to play also as one of the core players on All Things Must Pass.

Demos

John Lennon had begun working with legendary producer Phil Spector at the end of 1969, bringing him onboard to finish Let It Be in March 1970, and George followed suit, co-producing his new album with Spector at EMI's Abbey Road Studios.

Engineering was handled by a Beatles veteran, Phil McDonald, who would continue recording Harrison for many years thereafter. McDonald's first Beatles session was as tape operator (officially "2nd engineer") in June 1965, the day which produced "Yesterday," and later, in 1969, finished Abbey Road, when Geoff Emerick was pulled away to rebuild The Beatles' Apple Studios; the two won Grammys for their work on the album.

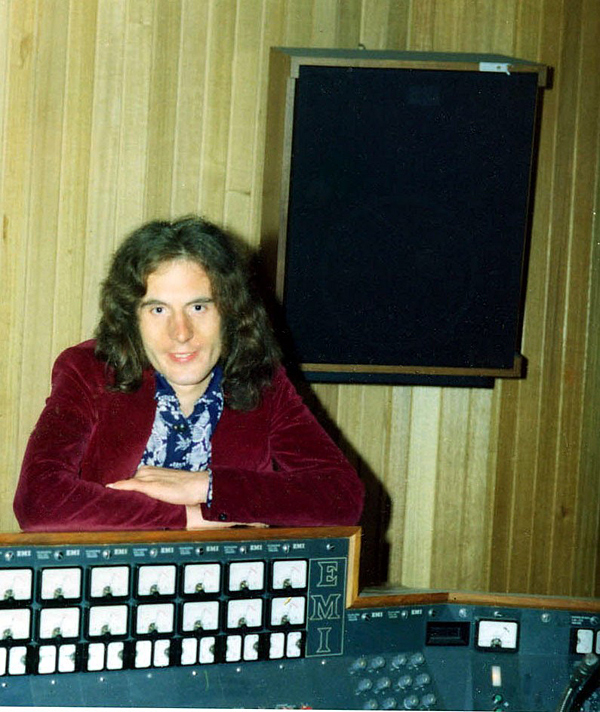

"His sound wasn't the kind of clean and clinical sound of Alan Parsons, but somewhere close to it," explains McDonald's 2nd engineer on All Things Must Pass, John Leckie. "He's a very soft Yorkshire character. Never gets upset or bad-tempered or edgy. And he always just gets this great sound. And without loads of gear, like today," just the EMI-made TG12345 mixing console (on which Abbey Road was recorded), Neumann and AKG microphones and Fairchild and Altec compressor/limiters – and that's it. "It was all done with EQ and mic placement." The recordings were tracked to a 3M M23 8-track tape machine, recording to EMI's own 1-inch EMITape.

Leckie himself started at the studio on February 15 of 1970 at age 20, as all newbies on the engineering staff do, as tape operator. "They tell you, 'You sit there – don't touch anything, don't say anything. Just sit and watch," he notes. The job entailed starting and stopping the tape machine – no remote controls in those days – and marking song titles, takes of each song on a tape reel, and the engineer's track layout (what instrument is on which track).

- Log in or register to post comments

Very good article, except you seem to have missed mentioning Hear Me Lord!

I think all the music is wonderful. I got the 5 CD version. I cannot understand why the Archival Notes booklet is only available in the Uber crate. Having no access to that, it is a pity your article did not indicate how many takes were required for each song, possibly including overdubs, and, above all, the master take for each song. All this information was contained in the books in the recent Beatles and John Lennon box sets!

Without a doubt, the Atmos mix is among the greatest I have ever heard. It is unfortunate that the album was not completed. It was a pleasure to read the piece. I had no clue there were so many outstanding artists penalty shooters 2 .

It's a shame that great works don't come to the tap tap shots loving public sooner.