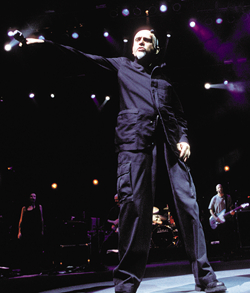

Peter Gabriel

Peter Gabriel's career got off the ground when he fronted one of Britain's top prog-rock bands, Genesis. He went solo in 1975. For this interview, we focused on his groundbreaking videos and his lifelong fascination with technology.

"Father, Son," the first video on your new Play DVD is wonderful. The images of you and your father together are incredibly touching. The video was directed by your daughter, Anna Gabriel?

Yes, and Anna was with us for the first leg of the tour to make a film about being on the road with her family. That's now been released as the Growing Up on Tour: A Family Portrait DVD. Soon after that, she showed me a treatment for the "Father, Son" video. Because she's family, the performances from the three generations of Gabriel boys were totally uninhibited.

I've read that you've produced most of your videos. The early ones were shot on film, not video, right?

Right. All of the early videos were shot on film, mainly as a quality issue. But also, in those very early days, film cameras were considerably more portable and easier to use than video cameras. Obviously, some of the treatments and final edits were done on video.

Some of them are pretty complex. I'm thinking about ones like "Sledgehammer." You can't shoot something like that in a day or two.

We would always lay out the ideas as storyboard videos first. That is one of the most enjoyable parts of the process—the brainstorming. And it was really great working with people who can visualize ideas and get them on paper quickly, but the whole process of making the video took about a month. First, we'd work through ideas with Stephen Johnson for a week, and then we'd spend two weeks in development with Aardman Animation and the Brothers Quay and a week filming in stop animation.

Were your videos a reaction to what was on MTV in those early days?

Were your videos a reaction to what was on MTV in those early days?

Not so much a reaction to other stuff—more a chance to play around and work with some interesting people. In many ways, it was the same motivation that led to the introduction of theatrical stuff into Genesis.

Ah, yes! Were you plotting out the videos as you wrote the songs?

Film has always been a stronger influence than theater. I think visually, and I often picture things when I'm writing, and things evolve when my collaborators throw their ideas into the mix. I have a wide range of musical influences, including church music, soul, blues, the Beatles, the Who, the Kinks, and the Yardbirds.

"The Nest That Sailed the Sky" on the Play DVD video collection may be the most beautiful video I've ever seen.

Thanks. I discovered that one while working with our very able multimedia department at Real World Records, which is led by York Tillyer, who created that video. We seem to be developing a knack for creating visual material from our own video clips and working from library material on the Internet. It's a lot of fun and enables us to produce interesting experiments quickly while staying on a reasonable budget.

You've said that listening to a CD is a completely different trip than watching a music video. Why do you think we can listen to the same song over and over again, but that doesn't hold true for most videos?

I think listening to music leaves plenty of space for our imagination, which is why repeated listening works well. When we're watching a video, the information passes through a different filtering process and ties up more of the brain.

Daniel Lanois and Richard Chappell created the new 5.1 mixes for Play. Were they working with your original multitrack masters?

Yes, Dan and Richard went back to the original multitracks for their mixes. I have always taken the view that music is a living thing and should be allowed to evolve. So, when we came to this project, I wanted some new additions. I was delighted with what Dan and Dickie achieved, and, in some cases, they produced better mixes than the originals. It's great to have enough space in the 5.1 environment to allow everything to be heard, and that wasn't possible in stereo.

I assume the earliest recordings were analog, but, by the early 1980s, you were using digital. How were they bumped up to 96/24 for Play's DTS mix?

Interestingly, even in the '80s and '90s, we used a mix of analog and digital sources for our multitracks. Before we started the mixing process for Play, all of this material was digitized in 24-bit resolution. We did it on the Sony Oxford console because it has some of the best digital converters we've heard.

Play might be the first DVD music video with DTS 96/24 high-resolution audio. I think that's great. What do you think is better about "better" sound?

Music is about an emotional connection between artist and audience. In our experience, the human ear has always been more sensitive than any recording technology. Higher-resolution audio gets more of that emotional message across. I guess it's like looking through a window: The better the technology, the cleaner the window and the better the view. But, as always, the real work lies behind the glass.

Switching back to CD after listening to SACD or 96/24, the music seems constrained, smaller, and less alive. And the MP3 is even more removed from the sound of real music—and listening to music becomes mere background for other activities. There's not enough "there" there.

Dan Lanois has argued for a while that the ubiquity of music has really devalued it, and, while I agree with some of that way of thinking, I believe much depends on the context, the environment, the company or lack of it, what else is going on emotionally, and the listening history of those present. Most people prefer the convenience of MP3, but it is a giant step back in quality.

As far as Play is concerned, I particularly like the 5.1 mixes on "Red Rain" and "Zaar" because of the way they open up spaces in the recording. Multichannel mixing is great—you can really put the audience inside the music. Because of the increased space, there is more room to put things in the surround field. This works particularly well for my music, some of which can be quite dense.

As far as Play is concerned, I particularly like the 5.1 mixes on "Red Rain" and "Zaar" because of the way they open up spaces in the recording. Multichannel mixing is great—you can really put the audience inside the music. Because of the increased space, there is more room to put things in the surround field. This works particularly well for my music, some of which can be quite dense.

We have yet to experiment with more than 5.1 channels, although, many years ago, we messed around with the height channels. This is also something I did when we mixed Up with my friend Tchad Blake, who has done a lot of work in the binaural arena [an early headphone surround-recording technique]. More than anything else, film is educating people about what to expect in larger-than-life sound environments.

I'm curious about how musical ideas are transformed by the process of making a record. Can you give us any examples of songs that are radically different than your original conceptions?

"Mercy Street" is an interesting example. I often fill songs up and then strip right back. The empty version can lead us to a new, more sensitive, and sensual approach.

You built Real World Studios in 1987 with the recording artist in mind. How have the studios evolved since they were built?

I believe we managed to create an environment in which artists from many cultures can be comfortable enough and well supported enough to give great performances, without which you can never have great recorded music. The biggest change in the way studios work has been the arrival of computer recording and in processing systems like Pro Tools and Logic Audio, as well as, obviously, a reduction in the amount of tape people use. It is amazing how much more time now gets spent poring over computer screens.

I know you're into advanced technology, but do you have any concerns about the death of analog tape or reactions to news that the legendary Hit Factory recording studio here in New York City is closing its doors? Has digital killed the analog star?

I think there is still a place for analog tape because of its unique sound, but the flexibility that digitized systems afford means they are definitely here to stay. I think it's great that digital technology has put music-making into the hands of anyone with a PC, but it has also put a lot of good studios out of business. I believe, in the case of the Hit Factory, where so much great music was made, there were other non-music-biz factors at play. But there is still no replacement for great-sounding studios and working in a creative environment. The whole retro movement worships analog, but I like to use digital and analog for different purposes.

Do you think today's artists are distracted with the minutia of business and technology?

I have always felt that the more the artists are involved in the whole process, the freer they become to create, and the results speak for themselves. Personally, I get distracted easily, but my other activities provide a rich and varied life.

It seems like young people don't want to make room for more stuff cluttering up their lives, and they prefer storing music and films as files on their computers. Is that where it's all headed?

I think there will always be a space for physical "stuff"; it is part of the way we identify ourselves. I think human beings are naturally collectors and will still want to keep the stuff that's most important to them. But my guess is that there will be a lot less of that than in the past. Digitized libraries of all media, whether at home or online, will be a much more significant part of how we receive information and entertainment.

You've recently started a new label, PRE Records. What's going on there?

We have always wanted to include more material based around good western songwriting. It's hard for rock artists to work through Real World's world-music tag, so PRE was created to feature some of these artists. Sizer Barker and Pina are the first releases.

Before we go, I have to ask: What are you listening to on your iPod?

Italian lessons and lots of unfinished demos.

* Our thanks to B&W Loudspeakers for arranging this interview. Extracts from Peter Gabriel's DVD, Growing Up Live, can be found on B&W's free promotional DVD, A Sound Experience, available from www.bw800.com.

- Log in or register to post comments