State of Love and Trust: Josh Evans on Mixing Pearl Jam in Atmos

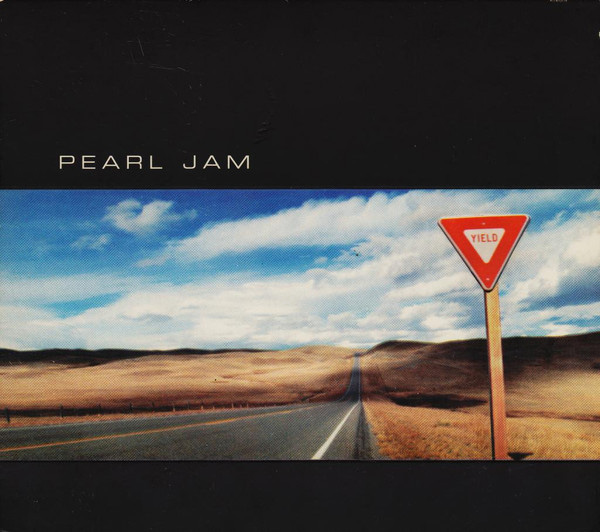

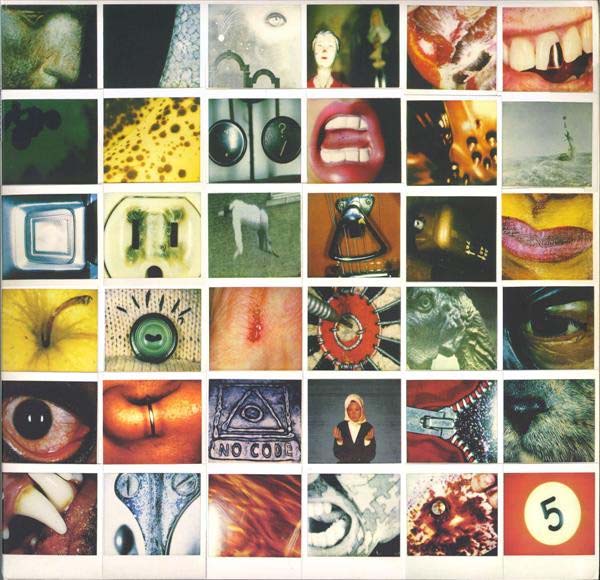

Pearl Jam essentially created their own lane as the 1990s continued to unfurl, with the intention of moving further and further away from the Seattle-bred G-word movement they helped pioneer by instead choosing to broaden their musical horizons on latter-decade albums like August 1996’s No Code and February 1998’s Yield.

Yield happens to be celebrating its 25 anniversary later this year with a deluxe 2LP set slated for an August 2023 release. Yield has also been given the green light for getting the full-on Atmos treatment courtesy producers/engineers Josh Evans and Nick Rives, a mix that’s already been available for full immersion via Apple Music Unlimited.

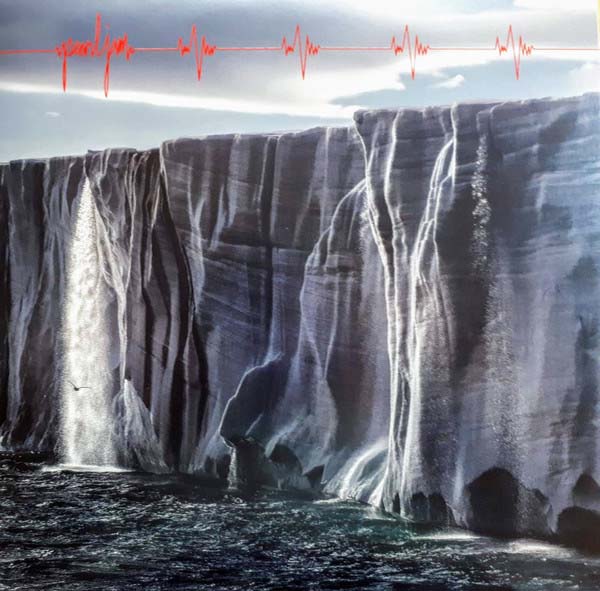

For his part, Evans (Soundgarden, Painted Shield) has been PJ’s righthand studio man for years, recently helming and engineering the band’s most recent studio album, March 2020’s Gigaton. (Incidentally, Pearl Jam frontman Eddie Vedder’s latest solo venture, February 2022’s Earthling, has a pretty decent Atmos mix of its own that’s also available on Apple Music — albeit one not done by Evans. You can read my thoughts about how coolly cosmic the Earthling Atmos mix is in my Spatial Audio File post from February 18, 2022, right here.)

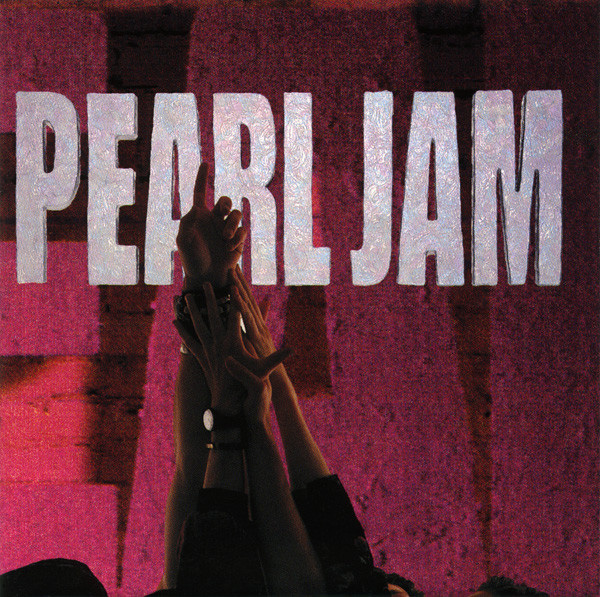

Evans has been responsible for a number of fine Pearl Jam Atmos mixes in recent years, including the band’s storied, 13x platinum-selling debut, August 1991’s Ten. “Getting to remix the records I loved as a kid in Atmos is pretty special,” Evans admits. “But I had a big concern with Ten, because that record’s so important to me. I know it’s really important for so many other people too, and I didn’t wanna mess it up.” Mission accomplished, Josh. Just cue up his push/pull Atmos approaches to “Alive” and “Jeremy,” and also dig how “Master/Slave,” the name for the brooding instrumental interlude that both precedes the opening track “Once” and follows the denouement of the last track “Release,” coils and unwinds all around you in an essentially infinite full-circle loop.

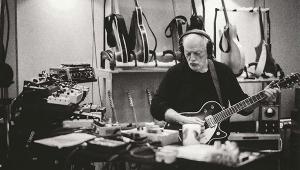

Recently, Evans got on Zoom with me from the friendly confines of his studio HQ in Seattle to discuss why Pearl Jam trusts his Atmos instincts, the rigorous multitrack tape-to-digital transfer process he follows, and why it’s important to sometimes just let the music breathe. He floated back down ’cause he wanted to share. . .

Mike Mettler: The first time I saw Pearl Jam live was at their New York City debut during the New Music Seminar on July 17, 1991 at a small club called The Wetlands, just about a month before Ten came out — and I loved them instantly. When did you first get exposed to their music?

Josh Evans: I was right there in Seattle in 1991, ’92 when I was 12, 13 years old. I stopped playing cello and started playing electric guitar (both laugh), so I was just right in the middle of it.

I remember going with my mom to a little store called Fred Meyer, which is a local Target kind of store here in the Northwest, and getting her to buy me Ten on cassette. My mom was like, “I don’t know who this Pearl Jam band is, but I’m gonna buy you Led Zeppelin I so you’ll at least get one good record out of this.” So, yeah, I got Ten and Led Zeppelin I on the same day.

Mettler: Wow. You went from One to Ten all at once in the same moment. Not a bad deal. (both laugh)

Evans: Yeah, I was two for two. Those are two pretty solid debuts.

Mettler: Seriously! And now, you get to work with Pearl Jam as both a producer, and as their go-to Atmos mixer. You’re their trusted ears.

Evans: I know! It’s pretty crazy, being trusted with all that — and I don’t wanna mess it up. Well, that applies to all their albums, of course, but I especially meant that for Ten.

Mettler: So far so good, I’d say. Which came first Atmos-wise for you, Ten or Gigaton?

Evans: Well, the first one was Gigaton. We finished Gigaton at the end of 2019. Scott Greer, and A&R kind of guy who works with the band and interfaces the labels, got the concept, and that was early on in the Atmos push. In fact, Gigaton might have been the first full-length album Universal put out in Atmos. There might have been a Coldplay and an R.E.M. record in there too — up until then, it was a lot of singles. But Gigaton was one of the early, first records that was released natively in Atmos as well.

I had already mixed the record, and Atmos wasn’t even on my radar. Then I went down to L.A., and I connected with Nick Rives, who really knows Atmos in and out. He’s done a lot of Universal catalog stuff. That’s what he does all day long, every day — he mixes in Atmos. [Rives is to the right of Evans in the photo below.]

Mettler: How did you get from Gigaton to Ten?

Evans: It was sort of a timing thing. I think it was the 30th anniversary of Ten and the 25th anniversary of No Code, and the label wanted to incorporate Atmos into the various reissues and celebrations they were doing.

For all these Pearl Jam albums — every single one, including Gigaton — we started from the multitrack, which gives us a lot of fidelity. Obviously, we’re working off the original tracks, but that also gives us creative opportunities. Not all the percussion is married to a stereo track that you’re then trying to spread. Every shaker, every tambourine, every overdub — we have individual access to them, and I wouldn’t want to do it any other way.

Ten had already been digitized, because [producer] Brendan O’Brien did a stereo remix of it a few years ago. So we had that one digitally already, but for No Code and, just recently, Yield — those tapes had never been transferred, so it was the process of going to the original 2-inch tapes, transferring them all, going back to the notes from 1995 or 1997, and trying to sort out what tape was used.

On Yield, we ran into stuff where all the vocals were right, but then there were two lines that were different on the 2-inch [tape] than on the CD. It turned out Eddie [Vedder] had gone back and changed a couple lines. Those two lines were sung on a Sony [PCM-]3324 digital tape machine, and then he flew in those two lines that were then cut into the master, or something.

Mettler: Are you allowed to say what those lines were, or do you want people to guess?

Evans: It was on “Wishlist,” and (slight pause) — I don’t remember off the top of my head. Sorry, I’m not being secretive.

Mettler: Understood. We’ll just have to listen carefully to find them.

Evans: Then it was a matter of transferring it off Sony digital tape — and, as you know, these days, there are not a lot of those machines around. It’s a multistage process. I get the multitracks, and we sorted out what the right takes are. The first pass on the project is taking the multitrack and then syncing the CD up to the multitrack — which, of course, drifts, because every time you play analog tape is slightly different, you know? But hearing stuff straight off a 2-inch analog machine is just great.

Mettler: Nothing better than original analog tape, I agree.

Evans: Nothing better! Going through it, I’ll come across an acoustic guitar track. They might’ve played acoustic guitar through the whole song, but then comparing it to the CD release I’ll go, “Oh, okay. They muted it here, and they turned it on and off there.”

Mettler: With a Yield track like “Low Light,” which highlights the acoustic guitar — hearing it in Atmos opens it up even more to me, as the listener. I now get something out of it I didn’t quite get on the CD, honestly.

Evans: Totally! On songs like “Low Light,” you really get that benefit of Atmos where everything kind of breathes. Stuff is less compressed, and you can hear more nuance just because you have that dynamic range — and you have that physical, spatial range as well. But it’s also really cool for the intimacy, and you can take away things that get in between you and the performance. You can hear the fingers sliding on an acoustic guitar.

That’s been one of my takeaways from doing these Atmos releases — especially with a rock band. Listening to pop stuff or artists like Lady Gaga or Ariana Grande in Atmos is incredible, because none of it exists in reality. It’s all synthesized. It’s all sound design, so you can put vocals everywhere. You could put a synthesizer in the background. You could have half the drum loops coming out on one side. It’s all sort of artificial — and I don’t mean that in a derogatory way.

Mettler: Yeah, I get it. They’re playing with all the space they have available to them, and they’re showing us what they can do with it.

Evans: Yes. And what we found, first through Gigaton and then further back, is that a rock band is three, four, or five people making one sound. The bass and the guitars and the drums are all like a freight train, you know? If you start pulling wheels off the train and putting the caboose in front of the engine, it all kind of falls apart.

But songs like “Off He Goes” on No Code, or “Low Light” from Yield, like you mentioned — that’s another way Atmos really shines. You don’t have stuff flying around and moving. Everything can just be bigger. You’re using the Atmos medium for fidelity.

I mean, it’s really interesting. It’s both a positive and a negative. There are all these techniques and tools engineers and producers learned to use for cramming all these sounds out of, originally, one speaker — and then two. Part of that is the magic that, when stuff’s getting printed to a half-inch stereo master, the kick drum hits and the whole console is sort of sucking down a little bit, or the tape compresses and there’s this inner relationship between all those elements in stereo.

In a way, one of the challenges with Atmos for a rock band is how to keep that interplay going when you’ve now broken that apart and spread it all around. The plus side is, you have to do a lot of damage to, say, Eddie’s vocal, to get it to fit on top of everything. On Gigaton, I had a lot of the lows cut from his voice on certain songs because you need that real estate for drums and guitar, and other things. In Atmos, he gets another octave. It’s like, “Take that filter off.”

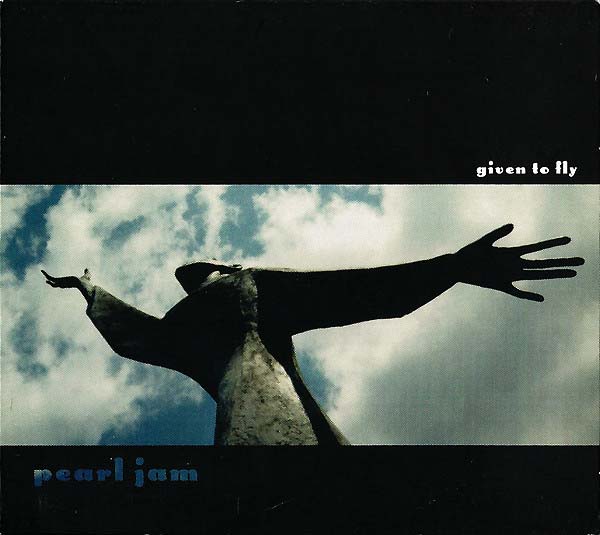

Mettler: On a track like “Given to Fly,” which is on Yield — it starts off ethereally and essentially up in the clouds, and when you get to the chorus where everything comes into play, you’re able to balance how we’re moving up here with the floating parts, and then you hit us right down the middle with the heavier parts. That gives you the space for Eddie to just unleash his full-on vocal howl there. You probably felt like, “I can really open things up here,” right?

Evans: Oh, totally. Totally. That one was really interesting to me. I’ve toured with the band for years [as a live engineer], and with that song in particular, I’m used to hearing 20,000 people singing along with it. I hadn’t gone back to the original recording in a long time, and it was surprising to me. There’s one vocal track on that song. There are no harmonies, and there are no doubles [i.e., no doubled-tracked vocals], but you still have all that power. It's one Eddie with no doubles and no harmonies, but it feels huge — which is great.

Mettler: I agree — it’s one of my favorite tracks of theirs in Atmos. To wrap things up, I’m sure you can’t say what you’re doing from the Pearl Jam catalog next in Atmos, but I have an educated guess. (Evans laughs) What else would you like to do in Atmos besides that?

Evans: Well, the catalog stuff is fun to do, yes. But what I’m excited for next would be to be involved in a project where Atmos was the prime format, you know? The music would be written for it. I’ve always thought it would be cool if, say, you have a singer/songwriter record where you listen to it in stereo, and it’s a guy and a guitar. And then you listen to it in Atmos, and it’s the guy and the guitar with a band, and then with an orchestra. I think that would be really interesting.

- Log in or register to post comments