Wayne Coyne, King Mouth of The Flaming Lips

That said, The Lips have also wrestled with loving the singular experience of someone sitting down to listen to any one of their 15 meticulously crafted studio albums all on their own, whether via headphones on in surround sound, while also continuing to encourage audience participation in the natural live communal extension. “Music has always been a bit of an internal experience,” Coyne concedes today, nine years after our above-quoted conversation, “though listening to it on headphones is kind of isolationist. It’s another way of saying, ‘I’m just listening to something by myself.’ But it can also be a great communal experience, where everybody’s listening to the music and cheering it on together at the same time.” (Hear here, and hear there, indeed. . . )

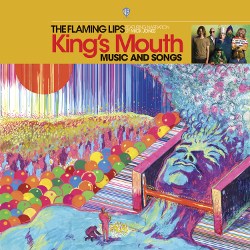

It’s this kind of push-pull listening fulcrum that brings us ’round to The Flaming Lips’ current release, King’s Mouth: Music and Songs (Warner Records), a concept piece that can be enjoyed both individually and collectively, and one that was initially released on limited-edition gold vinyl on Record Store Day this past April 13. Based upon one of Coyne’s most eye-catching traveling art installations, King’s Mouth (available now to one and all in multiple formats, as of mid-July) once again test the limits of the stereo soundfield, as far-reaching soundscapes such as the essentially self-descriptive “Giant Baby,” “Electric Fire,” “Dipped in Steel,” and “Mouth of the King” all readily attest. To thread each song chapter together, The Lips also enlisted Mick Jones, the onetime co-leader of The Clash, to serve as a most compassionate narrator.

It’s this kind of push-pull listening fulcrum that brings us ’round to The Flaming Lips’ current release, King’s Mouth: Music and Songs (Warner Records), a concept piece that can be enjoyed both individually and collectively, and one that was initially released on limited-edition gold vinyl on Record Store Day this past April 13. Based upon one of Coyne’s most eye-catching traveling art installations, King’s Mouth (available now to one and all in multiple formats, as of mid-July) once again test the limits of the stereo soundfield, as far-reaching soundscapes such as the essentially self-descriptive “Giant Baby,” “Electric Fire,” “Dipped in Steel,” and “Mouth of the King” all readily attest. To thread each song chapter together, The Lips also enlisted Mick Jones, the onetime co-leader of The Clash, to serve as a most compassionate narrator.

Coyne, 58, and I got on the line not too long after the aforementioned Record Store Day (which was also circa six weeks before his son, Bloom, was born on June 7), to discuss incorporating stereo-friendly elements into a mix, mastering the lost art of the song transition, and why having a great drummer/bandmate like Steven Drozd (at right in the photo above, with Coyne on the left) is crucial to a band’s long-term success. We don’t know how and we don’t know why. . .

Mike Mettler: I believe you sold out all 4,000 copies of the King’s Mouth limited-edition gold vinyl back on Record Store Day. Nicely done!

Wayne Coyne: We did, thank you — and we regret that we should have pressed a few more. We talked about it for so long — “Just go to your record store and get it!” — but I know there were a few record stores that really only had a couple of copies, and I was like, “Auughhh!” It’s great that it sold out, but I know it was really frustrating to people who went to a record store that day that didn’t have very many copies. So, hey, what can you do? That’s why we had to make the music available to everyone.

Mettler: It’s good to be in demand, I say. I listened to King’s Mouth digitally before I got the chance to put on the vinyl, and once again, you’ve challenged the boundaries of the stereo soundfield all throughout the record.

Coyne: Oh, well, thank you for saying that! More and more, our ear for that sort of thing has become better and better. I think you worry when you’re younger about what happens when you try to do things like that, but I think you just become more aware of it and how to really use it as time goes on. Plus, the stereos in cars have gotten better and headphones have gotten better, and people get used to this “thing,” even if they’re not aware of it. The world has gotten used to hi-fi, and that’s not just good for music, but for, well, everything.

Mettler: I agree. I remember back in the day how you personally had everybody at South by Southwest [a.k.a. SXSW] link up their car cassette players to play some new music of yours in unison, which was just a fantastic event to witness. [This particular SXSW event was held at the Central Parking Garage in Austin, Texas on March 15, 1997, wherein Coyne had between 30-36 cars play an electronic collage of sorts on tape in unison — at least, they all tried to play it in unison — essentially serving as a precursor to Zaireeka, The Flaming Lips’ 4CD experimental album released in October 1997.]

Coyne: Oh yeah! When we first started doing that, we were working with people who still had cassette tape decks in their cars (chuckles). I think for the very last one we did, we graduated to people having CD players in their cars, though it was difficult to find enough people in 1997 and 1998 who even had CD players in their cars. It was a long time ago! But the formats keep getting better and better. We just got a brand-new car, and we didn’t even have to get the mega-stereo package. With what was already in there, I went, “Oh wow, that sounds amazing!”

Mettler: With the playback quality being better, do you as a content creator consider it to be a challenge to feel like you have to, say, by the time we get to the end of a King’s Mouth song like “Electric Fire,” really go all out and zap things back and forth across the soundstage?

Coyne: Well, I think we’ve always embraced that part of it anyway. If everything is equal, you may as well please yourself, and that’s really our main default. Some of the things you do, some people might not even notice, but if they like you and they end up liking the song, to me, that’s already plenty. Sometimes, though, I can see people glazing over whenever I’m talking about things going from speaker to speaker.

Mettler: Well, not us! We love all that.

Coyne: (laughs) I think all of that is just a way of showing how much you care, and how much you want the listener to get and to love your message, you know? I mean, I don’t know if I want to do a 5.1 mix of every song every time, even though we were doing that for a short time. That would be, not overwhelming, but that would be a big job. You have to dig deep and go, “What are we going to do on this song that we haven’t done on the other songs?”

Typically, we’ve always done really good left and right stereo elements. Having those little things there just make for a better experience. It gives our sound its space and its dynamic, all the things you get to play with in the studio. We have all these things we’re trying to cram into our mixes, and we’ll take the 100 things we think should go in there and mix it all down to where it only sounds like four or five things, to where you can figure out what’s going on without you being too overwhelmed with too many sounds.

Mettler: As a card-carrying 5.1 geek, I do have to say, any time you want to give Dave Fridmann a surround-sound mixing challenge, I’m all for it. [Longtime Lips producer/engineer Dave Fridmann did the surround mixes for a number of the band’s releases, including May 1999’s The Soft Bulletin, July 2002’s Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots alongside Elliot Scheiner, and April 2006’s At War With the Mystics.]

Coyne: (laughs) Well, it is such a great experience, but it’s also like an isolationist experience. Only you are listening to music in this room that is situated perfectly, with you sitting in the middle of it. I think that’s why we like listening to music in our cars so much. We’re situated in a specific seat, and the speakers are situated around us — and we’re not going to move, you know? In my house, I would find it difficult to sit down in one seat and listen to a 5.1 mix for more than a few moments at a time anymore.

But I do love that we are making the music in that way, especially when we’re sitting in a studio that has such great sound quality to begin with. That said, some of my favorite listening experiences were listening to my mother’s record player that had one speaker in its plastic housing. I’m kind of easy! But if it’s a great song, I want to hear it in every format available. That way, you can hear different things in it at different times.

Mettler: I get that. Then again, a lot of us started listening to a transistor or AM radio under the covers on our beds at night, through some little speaker not even as big as your hand — though I guess some people are kind of doing that again now on their phones.

Coyne: I’m doing that exactly! I actually put my phone under my pillow, and listen with my left ear through my pillow. It really enhances the low end. I actually put my phone on mono so I don’t have to worry about which speaker I’m on, and I listen to mixes like that all the time. It’s quiet enough that it’s not bugging anybody.

Mettler: That’s an interesting way to do it! But I’m glad you still have hi-fi on your mind when you’re in the studio. On King’s Mouth, when I hear a transition of a song like “The Sparrow” going into “Giant Baby,” that shows the magic connection you guys have with that certain wave of creativity. While we always expect The Flaming Lips to push the musical envelope, there’s still that sense of “wow” whenever we hear music like this. You can take something we’ve never heard before, and turn it into “Mother Universe.”

Coyne: We’re really one of the groups that embraces the transition — the way this song ends, and that one begins. That’s a thing from our record collection that we probably latched onto — hearing somebody like Pink Floyd doing that extra little something in between and going, “It’s not just that that song ends and this one begins.”

These transitions are just our way of saying, “We love this. We love taking the time and putting all of our personalities into it.” And some of it is just very musical. You’re going from this song in this key and this rhythm and making this little passage that’s changing key and changing time signature, and then making all that flow. When I hear music that does that, it’s like you’re lifted for just this brief moment, into this world of the unknown. It’s taking you to that little special spot there.

But you wouldn’t want to be there too long. That’s why music works — it’s kind of mysterious one moment, and more familiar the next. You kind of know where it’s going, but then you have these little surprises. And they’re little surprises. They’re not surprises that last for an hour. Nobody would want that! (chuckles)

Mettler: It’s also nice that we have Mick Jones of The Clash acting as the album’s narrator, adding his South London accent into your mix.

Coyne: Is that what it is? I kept trying to figure that out! I keep hearing other British accents where I go, “Hey, that sounds like Mick!” I didn’t know that was what it is, but I have heard other people who have a little bit of Mick’s accent — and I just love it!

There was a Clash song that we kept referencing, previous to actually having Mick do the narration. It was a song off [May 1982’s] Combat Rock, “Death Is a Star.” You know, I’m not positive it is Mick — it might even be Joe Strummer! For the longest time, I just assumed it was Mick, but I could be wrong. [While Strummer is credited as the song’s chief lyricist, it does appear that the less-rough-hewn Jones vocal style is responsible for the right-channel narration on “Death Is a Star.”]

When Mick did the narration, we weren’t really in touch with him. Other people we worked with asked him to do it for us, and we didn’t really hear it until he did it. After we got it back, I was like, “Oh my God!” It really does sound like that guy who, in my mind, I was thinking would do this, just by listening to Mick Jones on The Clash records and Big Audio Dynamite, and listening to some of the interviews he had done.

I can’t tell you how much of a serendipitous, wonderful thing it is that he did somehow connect into our minds and said, “This is exactly what you want.” And it really was! I mean, there were a couple of words where I thought, “He must have known I wanted him to say it that way.” He did it in exactly the tone I was envisioning.

And we didn’t send him anything saying, “I want it to sound like this.” We simply sent him the text, so some of it is just uncanny how right we thought it was. I don’t know if it seems right to anybody else.

Mettler: I feel like there’s almost a sense of wonder in his voice, like he’s reading a storybook. He’s embodying the tone of the piece’s narrative, right down to the very end when he gets to the sign-off of “Bye!” It’s a nice personal touch that puts the final bow on it, I think.

Coyne: See, I totally agree! And that would have been something we wouldn’t have really known — and if someone else had said it, it may not have worked. I heard him say in an interview, where he was talking about when The Clash broke up and Joe Strummer and him were not seeing eye to eye, he said to Joe Strummer, “Bye,” in a way that was like, “I love you, but this is the end.” I heard that in an interview, and I thought, “Maybe he’ll say that just like that!”

And you’re right — there is something gentle and eccentric about his tone that reminds me of Boris Karloff doing the narration in [1966’s] How The Grinch Stole Christmas!

Mettler: There is a little bit of that to it, I would agree, and I also think there’s a little bit of Alfred Hitchcock in there too, in the way how he’d sometimes be a little bit playful in the front- and back-end narration he did for his [1955-62] TV show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Getting back to the songs themselves, is there one soundscape on King’s Mouth you’re the happy with the most?

Coyne: I think the one I’m happiest with is “Feedaloodum Beedle Dot.” I mean, Steven [Drozd’s] drums — he’s such a great, great drummer, and he’s always got these intricate things going on. He always plays the drum kit very musically — it’s not just whacks and thumps. There are always these great variations on the deep, sub low-end and the not sub low-end, and the distortion on the kick drum. You can’t really hear them if you have just a casual listen — but even through the pillow, you can hear some of those dynamics! (both chuckle)

He’s just such a cool drummer, and that’s really the star of that song. It’s the star of a lot of songs, but it’s the way it’s got this little off-beat that’s happening with the kick drum. When you jam along to it, you’re not quite that aware of it, but it gets you thinking, “I think it’s hitting that place, but I’m not quite sure.” Steven has such confidence in his playing, even though it’s quite tricky.

There’s just something about when you capture that thing, and it’s got a great sound to it. It’s almost like watching a fire in a fireplace, or a waterfall. It’s kind of predictable, but it’s also not totally predictable. It’s not the same thing, and it keeps renewing itself. His playing is often like that to me — with all these nuances and subtleties. We’ve captured it, and put it in a song where it’s really satisfying.

Mettler: Especially with the percussion that opens that track, which I’m going to call the “Onomatopoeia Track”. . .

Coyne: (laughs heartily) I like that! I like that. Sometimes, Steven plays the rim of his snare drum in such a way that’s kind of aggressive, but it’s laid back. It reminds me of Ginger Baker, or John Bonham.

Mettler: The other interesting thing about that track is how you manipulate the different vocals on it. You like to play with either volume levels or you varispeed it, to where there’s a “straight” vocal, then a higher vocal sped up — all choices you have to be making in the studio.

Coyne: I will sometimes be in the studio saying, “Somehow, you have to make that sound cooler,” and there are a billion different things you can go to. If you have to struggle too much, you can go down a pretty deep rabbit hole: “Well, it could be this, or it could be that.” But luckily, with the way Steven sings and the way we sing together, he’ll easily say, “If you’re singing this, then I can sing that.” If you were sitting there in the studio with us, it wouldn’t take much of that before you’d go, “Oh, that sounds great.” It’s so intuitive — “If you sing this, I can sing that” — sometimes I forget how much that happens with us just naturally, without having to construct it too much or think about it too much. It just happens.

For me, that’s probably the best thing that can happen with music. While it’s playing, it’s influencing this person to do this thing in the moment. They’re not writing it, they’re not thinking about it. It’s happening to them, and they’re reacting to it. Those are really our best moments. When the music’s playing and you have to participate, it’s one thing. When the music stops and you have to think about it, it’s another thing. I think some of my best lyrics have kind of happened that way. Going along, I don’t really know what I’m going to sing, and I just sing something.

Mettler: You guys have such a good working relationship over 15 studio albums, you intuitively know you can trust Steven when you go one way while he goes the other way — it’s a shorthand you don’t have to talk about too deeply. You just do it.

Coyne: Yeah, and there definitely is a joy in making and recording music. If The Flaming Lips have anything, it’s that we love making records. We’ve counted up all of our records — all the weird cover albums, and some of the ones we haven’t even released — and I think it goes up to 26 or 27. Not as many as, say, Frank Zappa or Willie Nelson. There are lots of people out there who have more records than we do.

Mettler: You’ve got time. You can get there.

Coyne: (laughs) Yeah, I agree!

Mettler: I also like how you have the vocal confidence to keep bringing it up another notch, going higher and higher as a song progresses.

Coyne: I’m lucky in that, as I’m getting older, I can sing even higher than I used to. I think that’s because I’m relaxing when I’m doing it. Sometimes it’s the opposite — the harder you try, the less freedom you have. Because we know we can manipulate it later and we can do things to it, you can relax and do more things when you’re singing, because you’re not trying so hard.

That’s one of the strange lessons of music. Like when we were talking about Steven’s drumming — often times, drummers think they’ve just got to hit those drums hard. When you watch Steven play, you’ll see how some of it is so light, some of it is hard, and some of it has a certain nuance. I don’t know if it’s confidence, or it’s like sleepwalking. The minute you know you’re doing it, you can’t do it. You just have to be in the moment. And that’s also because we record a lot. We go, “Well, if that doesn’t work, we can always try something else.” I see how that happens a lot. “Go play that again. That’s really going to work!”

Mettler: You follow your subconscious in the moment, and let instinct take over instead of thinking about it too much.

Coyne: It really does. The ability of getting that to take over — your subconscious is just some mysterious, weird sh--! But it is true. You know if something is too intentional, and it doesn’t work the same way as this other flow. I know, but I don’t think we’ll ever really know how it works. But we definitely know music is playing with that. Somewhere in the middle of all that, music must go into those channels and allow you to be in this deeper sense of yourself, and not even know it. Because your conscious mind is up here and in control all the time, I think when listening to music, it’s flowing through all of that — and that’s probably why we are all just so in love with it.

Mettler: I’ve often said that everybody is born with a sense of rhythm, since your mother’s heartbeat is probably the first thing you ever hear. Everybody has the ability to connect with some sense of rhythm and sound, and, once you get on the outside, it’s just a matter of how you decide to connect with it.

Coyne: Right! Out in the world, there are so many things that are rhythmic, as you start to pick up on it. You’re always hearing things. Your hearing is going all the time. It’s only once you focus that you’re listening. This ability to listen — that’s just a strange thing. There’s something uncanny about how music gets into you, even if you’re not listening to it.

These are the most musical times ever. You can be almost anybody, and you can be encouraged to make almost any kind of music. “You want to make some music? Do it! See what you can make of it.” It’s no longer just a musician in a studio with a producer — it’s almost anybody.

Mettler: It’s no longer exclusionary — it’s inclusionary. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Coyne: No. Especially if you love music, understanding it just a little bit shows you, “Oh, those guys — they are really great at it.” Anybody who gets to peer into how music is made and how it’s recorded and played and all that, I think you have a bigger appreciation for it because you know a little bit more about how it works, and how difficult it is to get that little bit of magic. The more you know about music, the more you see that some of it is just that magic. Everybody is trying, but why is the magic there sometimes, and sometimes, it’s not?

- Log in or register to post comments