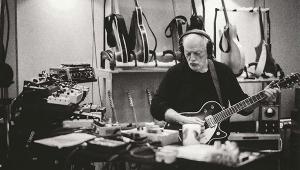

HT Talks To . . . Dennis Muren

Special Effects Guru Dennis Muren talks to HT about computer graphics, the equinox, and owning his own tux.

Special Effects Guru Dennis Muren talks to HT about computer graphics, the equinox, and owning his own tux.

Part of the original team at George Lucas' Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), Dennis Muren has led the visual-effects revolution from Star Wars through to the present day. He also directed his own feature film, The Equinox: A Journey into the Supernatural—begun when he was only 18 years old and completed on a total budget of $6,500. It's a special-effects extravaganza of teenagers and alternate dimensions that producer Jack H. Harris would later buy and writer/director Jack Woods would reshoot/recut. It was released in 1970 as simply Equinox. A magnificent Criterion Collection edition now offers both versions, with copious creator extras.

What are your feelings about the 1970 version of the film?

You know, I'm really mixed about it. I'm really glad that Jack made something professional enough to put in the theater so the film didn't just disappear. It's so different than the one we did. We were counting a lot more on the audience thinking about what's going on, to put the pieces together. And I thought they went overboard, but they were going for a drive-in audience, I guess, and people who are eating popcorn or doing something else while they're watching the movie.

Beyond your obvious passion for filmmaking, did you think this was going to be a serious calling card for the industry?

I thought it was going to maybe help me get work in the future, but there was not even effects work at that time. It was a union town. There was no way I could ever get work anywhere. It was a summer project and something that I just really, really wanted to do.

What did you do between The Equinox and Star Wars?

[laughs] Well, I was in college, and I worked on an industrial film on the universe. I did some commercials, but there weren't very many. I was ready to get into inhalation therapy or some other profession, which at least would have paid money. And then Star Wars came along, and I just loved the directors so much. After doing Equinox, I wanted to meet George and see what would happen.

At what point did you first think George Lucas might be onto something?

I couldn't tell from reading the script what it was going to be, but the sets looked great, and the acting looked really fun—they were putting a lot of money into the effects. I loved THX, I admired American Graffiti a lot, and I thought, "This guy knows what he's doing." But it wasn't until we saw it all together. He just kept saying, "Make the spaceships faster. Make the movie faster. Faster!" Then I went right from that on to Close Encounters.

Why didn't you do more directing until Star Tours, the Disney theme-park attraction?

[laughs] Well, I looked back at Equinox, and I said, "Oh my gosh, I'm just not good at this." I saw what directors go through working for studios. It's no fun. Unless you're one of the top people, you're being second-guessed everywhere. And, on Equinox, it was all just doing what we felt like, as long as I could come up with the money to buy another roll of film for the next week.

More recently, you took off an entire year to learn everything you could about computer graphics.

More recently, you took off an entire year to learn everything you could about computer graphics.

I had finished The Abyss, and it just seemed like I didn't know how the tools worked. So, I just took a year off on my own, got a 1,200-page textbook on computer graphics and read it every day at a local coffee shop. And I started doing research on digital composting and came up with a way to really streamline that process, which actually has made a huge difference in the quality of the work. So, then I came back in, and T2 came along. That was the opportunity to put everything to work, and that was the breakthrough film. And then Jurassic was after that.

So, you were the man as the world moved from optical to digital effects.

I mean, I wasn't programming the software or anything, but I was the person who was frustrated with the image. That's why I was kind of spearheading computer graphics [CG] on Young Sherlock Holmes and on The Abyss and saying, "Look, let's get it out, test it, and see if we can actually do it, if it delivers the goods, if we can afford it, if the image is better, or if it's just different." And it turns out it wasn't any cheaper, but it did make the stuff look a lot better.

Being at ILM in the '70s and '80s, you must have been like a rock star with the sudden mainstream attention given to special effects.

Yeah, maybe a local rock star, but I do occasionally get recognized on the street, so it's different than it used to be. It was just so hard for me when I was trying to find out anything about how this work is done. That's why I'm really free on talking to people about it, and that's one of the reasons I contributed to the Equinox DVD.

Pretty neat how you went from being a fan of genre films to the summit in your industry: A role model of sorts.

Yeah. "If he can do it, maybe I can do it."

Because people can do almost anything in CG now, have you noticed a trend toward flashier shots that call attention to themselves?

[somber] Yeah. And I think certainly they can hurt the movies, too. They just become effects films. So, everybody feels they need to top each other, and I actually feel the quality of the work hasn't continued getting better. It stopped somewhere.

It seems that the digital process has become less interesting to the outside observer, versus matte paintings, models, and pyrotechnics.

If you're looking at the process, absolutely. But, if you're looking for something that you can't do with pyrotechnics, wood, plastic, or paint, then you need to suffer through the sterility of making CG. [laughs] You know—working with people at keyboards in quiet rooms, because what you can get is just stunning.

Star Wars took traditional effects farther than anyone else had, but no one had ever seen anything like the liquid-metal man in T2 before.

Right. But people said they'd never seen anything like the dogfights in Star Wars at the time also. To me, the Star Wars stuff never really looked very real.

Right. But people said they'd never seen anything like the dogfights in Star Wars at the time also. To me, the Star Wars stuff never really looked very real.

Are you happier with the special-edition versions?

I am, I am! George and I are, I think, the only ones who wanted to do it! [laughs] What surprised me was that George wasn't going to keep the other version around, which I always thought needs to be around. Now he's released the laserdisc transfer back out again.

Do you like the way your work looks on DVD?

If the transfer's done right. Sometimes the effects can fall apart. But, other times, they can look pretty good. I think [cinematographer] Janusz Kaminski does great—the Spielberg films look terrific. But the garbage mattes showed on Star Wars. Stuff you never saw in the theater was showing up on DVD.

Have you seen any of your work in high definition?

No. Not at all.

Last question: As someone who's won nine Academy Awards and been nominated for seven more, do you own or rent your tuxedo?

[laughs] Actually, I held off for years, thinking it would be a bad omen, but I finally said, "Hey, I gotta buy one!"

- Log in or register to post comments