Stereo Is Father to the Surround: Al Kooper Talks 5.1

Both mixes gathered multichannel dust on the corporate shelves until almost a full decade later, when Audio Fidelity released them from captivity by way of a pair of Hybrid Mulitchannel SACDs. Here, Kooper, 71, and I discuss his surround mixing philosophy for both of those classic releases, why he’s not a fan of mono or streaming, and his alternate, Bloomfield-centric mix of Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” (on which Kooper played the infamous improvised organ riffs). There are no longer any 5.1 secrets to conceal.

Mike Mettler: Let’s backtrack to how the 5.1 mix for Super Session came about. This was done what, 8 or 9 years ago? Did somebody from the Sony SACD universe say they needed you to do it?

Al Kooper: They came to me and asked me if I was interested in doing it. It took me totally by surprise. I was very interested in doing it because I had never done it before, and they were putting up the money to do it. Not that I would ever see any money from it. (chuckles)

The point is, I jumped at the chance. In fact, they asked me to do both Super Session and Child Is Father to the Man, the Blood, Sweat & Tears album. So, I spent a week on each, and I got a wonderful education about mixing 5.1. I had excellent help in the studio with me. That helped me tremendously.

Mettler: Who was that? Who was your help?

Kooper: Steve Rosenthal, the owner of The Magic Shop Studios in Manhattan, which are pretty great studios. And his assistant, Matt Boynton, who was really a big help.

I did the Super Session album first. The main problems you face with something like that are the comparative, antiquated recording techniques — which, of course, have changed radically since the time the album was originally recorded. So you have to work around that.

These were both 8-track recordings. On Super Session, it wasn’t as much a problem, because we were dealing with quartets and quintets. Whereas with Blood, Sweat & Tears, it was an octet, so decisions had to be made in terms of track placement. But not on Super Session. That was easier to work with, which was one of the reasons why I chose it first. It was recorded brilliantly originally. The engineering was terrific. That was a big help.

Mettler: Before that, there was a 2003 Super Session remaster for CD. You’d brought it up to 24-bit at that point, so you already knew from that session you had good stuff to work with, right?

Kooper: Yes. Yes, definitely. The original work on it [in 1968] was probably my first production for Sony. There were some bizarre things I did. For instance, “Season of the Witch” —

Mettler: You mean the tempo edits? [Kooper sewed together two different-tempoed takes to get the final cut of “Witch” that’s heard on the album.]

Kooper: Yes. Those are what I consider nowadays really bad edits. (chuckles) But a really amazing thing happened: a) nobody called me on it, and b) people believed we made those changes as musicians.

Mettler: You talked a little about that in your book [1998’s Backstage Passes & Backstabbing Bastards: Memoirs of a Rock ’N’ Roll Survivor; a second edition came out in 2008].

Kooper: Of course, I was faced with those edits again, like a knee in the groin to remind me where I came from. In retrospect, I’m glad I made them, because I got the best out of both takes, which was certainly my goal. There were only two takes, so I didn’t have much of a choice. But I really did get the best out of those two takes, so I’m not sorry for that. I’m just sorry about my methodology.

Mettler: Is that a case of the emperor laid bare, so to speak — was it something superglaringly obvious when you listened to the playback?

Kooper: No, not really. I said, “People will just have to think that’s how we played it.” And that’s exactly what happened. But the engineer, you know, laughed at me. It’s not easy.

Mettler: Did Steve [i.e., Stephen Stills] say anything to you about it?

Kooper: Oh no. It was like I had hired him for an evening. He came in and played, and then went, “See ya!” It was like that. He was very different back then, as a person. He was very quiet, and he just stepped up to the plate and played great. I had always been a fan of his guitar playing. I had to call every guitar player in California that I knew because this happened so quickly [i.e., Mike Bloomfield up and leaving the sessions with just half of the album completed]. And he was the one who called me back.

Mettler: You made the right call with Stills. Time has born that out.

Kooper: Yeah, yeah, it was great. The only thing I regret — though it was a wise move — is I couldn’t let him sing, because I hadn’t done any business on it first.

Mettler: Right, because we’re talking two different record companies being involved [i.e., Atlantic and Columbia].

Kooper: It was a big deal, it turned out. It was part of the negotiation for Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Mettler: Otherwise, Steve would have been billed as “L’Stevio Mysterioso.”

Kooper: (chuckles) Uh, yeah! The next time I saw him, he was in the company of David Crosby, who said to me, “Why didn’t you let him sing?” I told him, and he just shrugged his shoulders. He wasn’t cleared. He was signed to Atlantic, and this was a Columbia record, and I had no time to negotiate. I hired him for the session. And, you know, the lawyers worked it out.

Mettler: Tell me about your goals for all-channel placement for “Season of the Witch.” How did you want that mix to come across in 5.1?

Kooper: There were certain things that annoyed me that I’d read about other people having done — such as some jazz recordings where they said, “Everyone is placed exactly as they sat in the studio.” And I went (sarcastically), “Well, that’s very important! That’s going to help the sound out.” I thought that was ludicrous. I said, “This is 360-degree sound with height involved. Who gives a shit where everybody sat?” I just want everybody to clearly hear all the musicians and not have it be as “crowded” as the stereo is.

And I’m not a big mono fan. Mostly because on records that were originally mono, people went back, and, because there were multitracks of some sort, made stereo mixes. Some of those stereo mixes were incredibly educational for me, as a student of production and engineering.

Mettler: If we were to look at the ’60s output of Bob Dylan, some of which you were on yourself, what’s you feeling of mono vs. stereo with his recordings?

Kooper: Like I said, I hate mono. That’s my feeling. (laughs)

Mettler: Even the ones you played on —

Kooper: I don’t care if I played on them. I hate mono.

Mettler: So “Like a Rolling Stone” is much better in stereo, in other words?

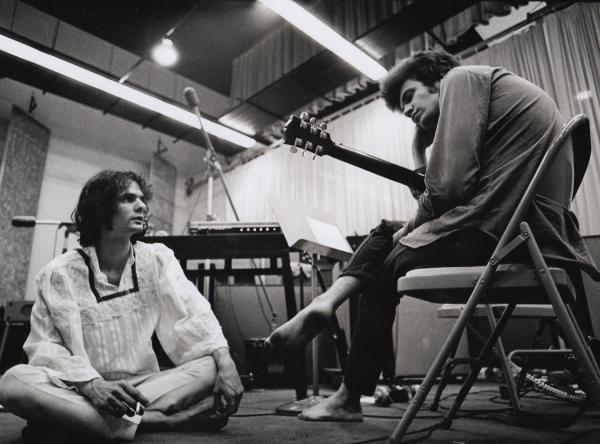

Kooper: I don’t know if it’s much better. It’s just that — on the Mike Bloomfield box set I did last year [From His Head to His Heart to His Hands: An Audio/Visual Companion], I asked for the multitrack tapes of “Like A Rolling Stone,” and I took Bob’s voice out and remixed it in stereo to show all the interesting playing that went on that is obscured by the official mono and stereo mixes. I actually made the organ lower and the piano and drums louder — and Bloomfield always played loud. (laughs)

Mettler: In terms of sonics, is 24-bit the best representation of how we hear this music?

Kooper: I don’t pay that much close attention to that, technically speaking. I’m not really a technophobe as much as I am a crusader. I want to do the best job I can do on a project in terms of the mix and the mastering and all that so that it sounds best. But I’m thinking more musically and soundwise than technically.

Mettler: What in your mind constitutes a good-sounding mix?

Kooper: In 5.1, I think it’s great if you can hear all the details in a person’s playing. Obviously, you can’t do that if you’re mixing Count Basie, or something like that, just because of the size of the band. That’s what I was trying to do on Super Session — place everything so that you could hear the details of the playing. I don’t think I moved people around. I picked the placement and just tried to get the best possible sound. The balance was very important. I was hoping that the listener is smart enough to find the sweet spot.

Mettler: When “Albert’s Shuffle” gets going, and you hear somebody yell, “Hey,” did you have to make any choices as to where that come about in the soundfield? What did you have to do there?

Kooper: Well, I didn’t really have a choice. That was on the guitar track. It was probably picked up by the amp mike. It was Bloomfield who said that. I love things like that. Certainly, that’s evident from the Lynyrd Skynyrd records I did. I loved the talking, because it takes you there. I’ve always tried to do that.

Mettler: Now tell me about the 5.1 mix for Child Is Father to the Man.

Kooper: The Blood, Sweat & Tears one was totally different. That has insane panning and balances. That’s the spirit that it was originally done in. It’s much more complicated, and there were a lot of problems to overcome. Super Session was comparatively easy.

For instance, because of the size of BS&T, the engineer [Fred Catero] put the guitar and the bass on the same track. When they did the quad mixes, there was no way around that. Today, you can separate them by subtracting frequencies that are comparatively foreign to each instrument. I’m not saying you just push a button and it’s done, but we separated the two instruments and put each in its own location. So we used technology in a useful way. Matt Boynton went through the mono drum track and extracted the various drums — i.e., kick drum, snare, hi-hat, etc. — to new locations. I still kept the drums in mono, but I had control over the mix of the interior kit as a result. So, again, technology was used in a helpful way.

Mettler: I love that we can now have high-resolution files too. Have you dealt with Pono and Neil Young at all?

Kooper: Nope. I’d like to hear it sometime. I’m all for that.

Mettler: Then there are those people who think streaming is the future.

Kooper: I love the convenience of technology, but not renting. I hate streaming. I hate it. The thing that I like best about it is that when the next thing comes along and streaming is antiquated, Bob Lefsetz and all his friends will have nothing they streamed instead of purchasing to play back, because they just rented it, and in the foreseeable future, the landlord and the property will just be gone. Kids today didn’t grow up really owning anything. They can instantly get what they want on their phone, fer chrissakes. Believe me, it will be no loss to them when streaming dies. They’ll just go on to the next thing, Most of them are not comparative lifelong music collectors.

Mettler: I happen to like owning what I’ve got and having a physical library. I still have a nice combination of Blu-ray, 5.1, CD, vinyl — everything.

Kooper: I have a room that’s just LPs and 45s. I don’t particularly need them anymore. I am thinking of selling them, because they’re all transferred. But I’m also terrified that, what happens if you can’t play MP3s in my lifetime?

Mettler: Good point. I think things like 5.1 put the focus back on listening and not being distracted.

Kooper: That’s why I don’t like mono. It’s not because of 5.1 — it’s because of stereo. As for 5.1, I don’t think you have to go spinning around the room; just make enough room so that you can hear what each instrument is playing. That’s the whole point of it to me.

Mettler: Some stereo mixes became quad mixes, like Chicago Transit Authority (1969).

Kooper: I remember that very well, because I was there. I was working at Sony when they were doing that, and I stayed away from it. Of course, quad didn’t make it. I have a theory why quad didn’t make it. (chuckles) The audiophiles were definitely very excited about it, but then they hit the wall of having the women say, “You want to put how many speakers in my living room?” I think that’s what killed quad.

Mettler: That’s known as the WAF in action — the Wife Acceptance Factor.

Kooper: (laughs heartily) That’s exactly what I was saying! Between the time of quad and 5.1, another thing happened that dispelled your WAFs, which was keeping up with the Joneses. When 5.1 first started, the housewives couldn’t overrule it. Because then their living room would be hipper than the neighbors.

Mettler: To wrap things up, what are you working on now?

Kooper: It’s the most intense thing I’ve ever done. It’s a four-CD box set of everything unreleased from my career. It will simply be titled Unreleased, and contain 60 years of unheard demos, tracks, and productions. I’m trying to do the release that would be the ideal one to be done at my death. I wanted to do it while I was alive, because nobody else knows about this stuff, or knows where it is. I wish I could make a deal that they couldn’t release until I died. It will obviously be better than what the record companies scurry to purvey.

I think it’s going to be released through Omnivore. They impress me. They came out about a year ago and listened to everything. Not only could I not get anyone else to do that, no one else was willing to give me four discs. I won’t be able to put everything on the four discs, but it’s better to pick and choose at that point. The early stuff is pretty hilarious, from when I was doing songwriting demos.

Other than that, I spend a great deal of time on my weekly column and play the occasional gig because I guess I will always enjoy playing out live. If I can’t do a good job, then I will stop doing that — but so far, so good.

A longer version of this interview appears on Mike Mettler’s own site, soundbard.com.

- Log in or register to post comments