Remote work opens up opportunities for employers to hire talent from anywhere in the world, rather than being limited to a specific geographic location https://picoworkers.org/. This expanded talent pool increases the likelihood of finding the best candidates for job openings and promotes diversity within the workforce.

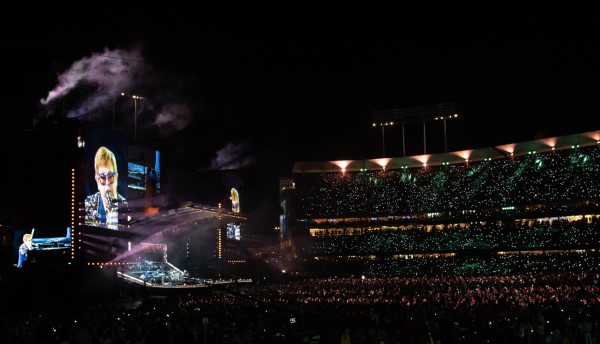

Elton John: Farewell Yellow Brick Road Page 5

Dugdale also used a long lens audience camera. “They call them ‘audience sniper cameras,’” informs Bobby del Russo. “Because they’re hoping for some celebrities—and I think they got a couple. A lot of times, those are set some distance away. Because when you put a camera in somebody’s face, you don’t get a true reaction. So you don’t want them to know they’re being shot.”

One surprise moment did indeed pop up—a fellow proposing to his girlfriend—which made it into the cut. “Nobody knew that was going to happen—it was totally serendipitous that the operator was right there,” says Rhodes. “We didn’t know that was happening, and then, one of the producers was keeping an eye on the monitors for good moments, suddenly went, ‘GO TO CAMERA 5 NOW NOW NOW NOW NOW!!’” he laughs.

There were several ways Dugdale captured the scale of the venue, from inside it, around it and above it. Since drones cannot be flown over an audience in Los Angeles, a wirecam was used to fly over the crowd. “We originally wanted a Spidercam,” the kind of camera system one sees when watching a football game, which can move in three dimensions—lengthwise along the field and side to side—as well as raise and lower the camera, vertically. “But Los Angeles Fire Department regulations don’t permit it,” informs Rhodes. “So we just did a point-to-point system,” running a camera along a single cable, strung between columns across the stadium, held in place with cable anchors.

“That shot,” says del Russo, “and that angle, up that high, is really just about the event. You turn it and you move it, just to get a little bit of movement, and it makes it seem immense. But you have to start full wide.”

A drone was also used. “We were just expanding out from what we were doing, trying to show the scale of the venue on the floor,” Rhodes explains. “Then we have the wirecam, trying to show the scale of the venue, inside it. And then, the drone was, ‘Let’s do that again, but let’s get just a little bit of foreground momentum, when we go past some of the stadium lighting.”

Turnbull and Dugdale spent quite a lot of time on Google Earth, figuring out shots they wanted to get, though, again, Fire Dept. regulations prevented quite a lot of it. “You can’t fly over the audience in the U.S. and the U.K.,” says the director, ‘but you could circle the perimeter of the venue.”

In the end, it was used to get some pretty awesome shots, most notably starting on the roof, way up above home plate, rising up over the iconic “Dodgers” logo atop a roof structure, and continuing up to reveal the stage in the background and the stadium full of fans. “That was certainly one of our ambitions, to get that shot,” says Turnbull. Adds Dugdale, “I love it when you can use it as a reveal. You start, you can’t see it, and you rise up, and you’re like, ‘Whoa—there it is!’ You’re at Dodger Stadium.”

Expanding on the idea, a helicopter was employed to get big, geographical wider shots, to set the stadium within the environment, within the city, Dugdale notes. “You had the drone, which would do the close stuff and the dynamic moves around—a brilliant, perfect, huge wide shot. And then, a helicopter would be the step back, that sets the whole space in the context of the city. We used it quite a bit, mainly in between songs—just to kind of check in with where we are, to remind people that you’re in Los Angeles.”

Turnbull, once again, created a previsualization for Dugdale, with a scale model of the stadium, and a flying camera in virtual space, to show him shots and lenses. “But, ultimately,” he says, “it was about an experienced pilot and experienced camera operator, who knew the cityscape and could offer up the most appropriate images.” And, unlike drones, helicopters can actually fly over the stadium.

To man all of these many cameras, Dugdale took full advantage of Bobby del Russo’s years of experience and relationships with these best folks in the business. And it wasn’t easy, at that particular moment. “It was one of the busiest weekends in L.A. in a long time,” notes Rhodes. “There were, like, seven shows shooting, so it was hard to get operators.”

Del Russo drew from ops in not only L.A., but also his many friends in New York and some in the U.K. “I do know a lot of the L.A. guys, but it’s a lot easier for me to get people in New York,” he explains. “I can go to my friend and say, ‘Dugdale called, he’s got this thing. Put these dates aside.’ That’s how you get those guys in place—lots of phone calls.”

To prep the operators, Dugdale held a long camera meeting on the day of the shoot (and on Day 2, as well). There is no “camera script,” specifying every single shot. “We busk the whole thing,” he notes. But every song, every camera has a specific role, and sometimes specific shots within that. So the director creates essentially a “bible”—50-page camera booklets with specific notes for each camera and for every song.

“The meetings are very long and intense,” describes Turnbull. “Paul’s notes give guidelines for each operator’s camera, their role, both generally and specifically for each song.” Says Rhodes, “Paul will tell them, ‘Guys - you don’t need to read all of that, but if you need to know something, it’s in there. I don’t expect you to be reading this while we’re shooting. But if you read it now, and make your own notes, you’ll have a little cheat sheet near you.’ It will have notes, like, ‘Camera 6, I’m really relying on you to get this, this and this. And, in this song, it’s gonna be perfect at this moment.’ So all the operators have their ‘hymn sheet.’ Paul’s done his homework—and he wants them to do theirs.” Adds Dugdale, “On a show with 28 cameras, I can’t communicate all I need live, so this gives everyone a head start.”

Dugdale will lay out, during the meeting, specifics even for camera pacing, to make sure a camera is already moving when he is ready to switch to it. “He’ll tell them, ‘I want to use really long shots, so I don’t want you to get to the end of your track, while I’m trying to use you. So take your time to get there,” Rhodes explains. “When you’re filming live music,” the director says, ‘you need to be in the right place at the right time. So as one song is coming to an end, the camera guys will look down and have a look at what they’re doing next, and make sure they’re in the right spot and in the right angle, position, lensing, to get what is intended. It’s a live broadcast—you can’t be late, because then you’ve missed it.”

One other important thing that comes out of the camera meeting is making sure each operator fully understands their role in the show—and sticks to it. “I used to be a camera operator,” Dugdale explains. “And sometimes, you’re, like, ‘Well, I think it should be this. But these guys shoot multi camera all the time—they’re part of this huge camera complement. So even though your camera might be able to get a great shot, another camera probably has that role, and is in a better position, better lens, than you are. Your role is ‘X.’ Everyone plays a part. The 28 cameras all complement each other.”

“It’s important they understand, and hear at the meeting, ‘This is why you’ve got that lens. Please don’t complain and ask for a different lens 5 minutes later,” says Turnbull, “because it’s important you understand, this is supposed to do this job. We’ve been through it, in a lot of detail, and this is your role on this show.’”

A Change in Light

Patrick Woodroffe was the tour’s chief Lighting Designer. But lighting beautifully for a stadium audience is different from what is required for television cameras. As cinematographer, Brett Turnbull would normally be tending to lighting changes at the venue, but since he knew he would not be on site, personally, he handed off lighting duties to Emmy® Award-winning Lighting Designer Noah Mitz, who has worked with Dugdale on a number of projects, including CBS’s Adele special at The Griffith Observatory, to adapt Woodroffe’s design for filming.

“I’ve literally lit hundreds of shows for television,” Woodroffe explains, “but my focus is always on the big picture—how we can capture the atmosphere of the occasion, how the artist will respond to the changes in the show, how the audience is lit. Because Noah is guided by the camera plot, his thinking is much more critical. “What am I actually going to see in this shot beyond Elton, himself? What’s going to be in the background? Where will the lens flare be?’ And perhaps the most important thing in lighting for television is the balance between all the different light sources. For a live concert and a live audience, we want to make Elton the main focus on the stage, to shine brighter than everything around him. But, in fact, Noah would often be saying, ‘No, let’s take him down a little,’ because the light on Elton has to be perfectly balanced with, for example, the light on the drummer, who’s in the background.”

Mitz also was conscious of things that, when viewed from the audience, looked fine, but when captured on camera, may have introduced unsightly flaws in the image. “We spent a lot of time addressing the background of Elton’s closeup,” from the distant Camera 5, noted above, says Mitz. “90% of the show, by nature, he’s facing that same direction. From a live perspective, everyone in the stadium’s looking at him from downstage. But cameras are looking at him along his axis of the piano, which means there’s plenty of background set structure and equipment visible behind him. So we’re thinking, ‘What exactly is back there? What can we do to add lights behind there, and make it so that it matches Patrick’s lighting, so that it all looks like it’s part of the same show?’”

Besides his work for the camera and lighting balance, Mitz had another charge. “Our primary directive was to bring the show that Patrick and his team have been doing for years, that exists within a stadium, and take it and fill it out, across all of Dodger Stadium. So we had to light not just the audience, but the building. And then create a system which reflected the existing cueing in the existing show, spreading across the stadium.” Adds Dugdale, “It’s an iconic landmark, particularly with regard to Elton’s history, from his show in 1975. It is a character in the piece.”

“Noah was very clever,” Woodroffe says. “We don’t want to light the entire place up. What if we only lit the top level, and had something halfway down? We want source points of light, coming towards you, that give you the geography of the place. But you also want to have a light that actually lights people’s faces—but not light their faces all the time.”

Mitz and his team, headed by gaffer Matt Benson and lighting director Bryan Klunder, spent a good deal of time working with the stadium’s Facilities Management to figure out how to add the lighting he desired. “Dodger Stadium doesn’t actually host that many concerts, particularly ones that have added lighting throughout multiple concourses. So we had to find out, what can we do, where can we do it—and what < we do? It was really a puzzle, finding ways to run all of that cable.”

He created two rings of lights, one on the Loge level, which sent light down to the field, and also lights attached to columns of the upper deck. And, of course, much of it in classic Dodger Blue. “The stadium has an identity, a brand. And supporting that is important,” he points out.

Dugdale was also keen to make sure to add more audience lighting. “When you come to film a show, you want to see where you are. You don’t want to just see a stage floating in a big black hole, that could be in space,” Turnbull notes. “For viewers at home to experience the atmosphere and excitement of a live concert, they need to see enough of the crowd and the stadium, to immerse themselves in that environment. So we always try to add some audience lighting, and play along with the show - so it feels naturally motivated by the stage”.

On the other hand, you don’t want to light them so much, it becomes a distraction for them. “We called it through, carefully, with Elton, David and Paul,” Woodroffe notes. “’When should we light them? What is going to be important? Give us some numbers where you don’t want them lit.’” And, certainly, when Elton is talking to the audience, and for applause moments and call-and-response moments, those are times when we want to see the audience—and Elton wants to see them.

When Furnish and team were originally thinking of how to make the final Dodger Stadium show special, among his suggestions was LED wristbands. Upon entry into the stadium, 50,000 such devices were handed out, each featuring a 1” square light with two multicolored LEDs inside. And at times during the show, the LEDs light in different colors and patterns, thoroughly exciting the audience. “They’re like a low resolution video screen with 50,000 pixels,” describes Woodroffe.

Dugdale has used them multiple times, notably in Coldplay and Taylor Swift shows, firstly on a Coldplay concert back in 2012. “They make people, in the space, feel like they are part of the show,” he says. “They unite everyone. And you feel the excitement in the space—we see it in people’s faces, literally, when we’re filming them. The whole space becomes the stage. They were a really nice addition.” Notes Turnbull, “It’s another way of lighting the audience, without just having to point lights at people. And it’s fun. The audience loves it, because they can be involved.”

The company that makes the wristbands—and programs their display—is called, appropriately, PixMob. The Montreal-based company developed the system 14 years ago, specializing in what PixMob Director of Tours Hila Aviran calls “wireless lighting.” “We just like bringing humans together through light,” she says. Their technology has evolved from a limited amount of colors, blinking and pulsing to the music, to now being able to control several hundred thousand people with a couple of transmitters. “And program them, wirelessly, to create really advanced effects, which five years ago, needed a ton of time. We don’t have to do that anymore,” with the type of advanced programming seen here arriving within the last five years.

The LEDs are activated/controlled via sets of infrared transmitters, which have the appearance of regular Par lights. “We have 32 of these installed, in static positions, on the two light towers the tour has, and they send an ‘infrared wash’ of infrared light to the entire venue.” The programming works using a variety of lighting effects that go beyond on/off to the beat of the music, such as a probability effect, which tells the wristbands to randomly light, say, 30% red, 30% blue and 30% white. In addition, there are also four moving heads, which produce infrared patterns that sweep across the venue, some produced by gobos attached to the heads, producing interesting graphic patterns across the crowd, as they move. “We control where they paint light on the audience,” Aviran describes.

The programs for each song are created in-house by lighting programmer and operator Nicolas Coallier Fournier—Nico, as he is known—working first creating the designs in a computer visualizer, with a CAD file of Dodger Stadium, to see how the design will work for a song. “Patrick Woodroffe gave us the songs and the feeling he wanted to create, and which colors, and we would create some designs and patterns, and send a visualization back to him, going back and forth until his vision and programming align with the design,” she states.

On site, Fournier actually does live programming at a lighting console, where he is set up at the front-of-house, next to the other lighting controllers’ desks. “Nico will arrive five or six days in advance, to study the music and how the band performs it live, watching rehearsals and listening to the songs over and over again and watching.” He programs the moves for the selected songs, wearing infrared goggles between programming steps, to test how the visuals will look on the crowd. Fournier has specific effects he has pre-programmed into the desk, but, during the show, he is essentially playing the lights’ performance live, as any lighting director would.

Unlike other artists, who might use the LEDs throughout an entire concert, Woodroffe was keen to make limited use of them, to avoid them simply becoming a gimmick. “I said, ‘Let’s not overuse these things.’ We chose six numbers,” including “Tiny Dancer,""Rocket Man” and “The Bitch Is Back,’” he, Furnish and Dugdale sitting down and asking themselves, ‘Which songs should we use it for? What’s the first song they should come on? “That’s a big decision,” says Dugdale. “Or for an intimate song, ‘No, let’s just hold it back for that, and feel the intimacy of Elton’s singing.’” For songs when they are used, regular audience lighting is needed far less—the wristbands are doing the lighting.

Woodroffe made sure the LEDs were integral with other features of a song’s design, instead of being a standalone lighting feature. “Patrick was very clear,” states Aviran. “They needed to be aligned with their design. He didn’t want it to just be a light-up accessory in the crowd. They needed to be part of the show. He wanted it to be classy and elegant. He didn’t want it to feel cheap.”

Says Woodroffe, “We started to tie them into other content. For ‘Rocket Man,’ we have a wonderful space scene put together by Treatment, up on the screens, that goes through the whole number. You take this lovely journey through the planets, coming towards you. And my lighting is shining in the audience, with breakup patterns that are the same color, pitch and movement, and Sam has added those in the stadium’s ribbon screens. And the PixMob lights are creating a star field in the audience. So the same dots of light we have from PixMob are being repeated as a star field on the ribbon. The audience doesn’t know what they’re looking at—they just know that they’re in outer space.”

During the show, there were also a lot of live cues—“Moments where it just felt right to go live, where Nico would just play what he felt,” Aviran explains. “There might be a cue for a song which was a little more subdued, but the crowd was energetic at that moment. So Patrick would just tell Nico, ‘Do your thing. Just go live. Do what you feel,’” and Fournier would just create patterns which fit the moment.

- Log in or register to post comments