I wish Pono all the luck in the world...I'm just not sure there's a big enough market willing to pay that much for music anymore.

High-Resolution Harvest

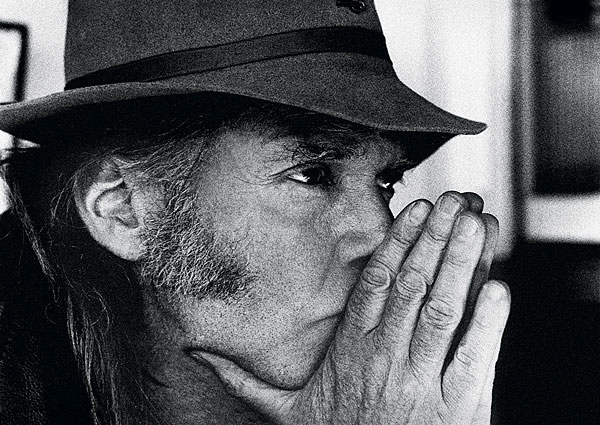

If there’s one thing we know about Neil Young, it’s that he’s deeply passionate about how his music gets heard. As an artist who’s long championed sound quality over final-mix compromise, Young has been on a lifelong quest to make sure listeners have the opportunity to hear his music the way he intended from both the studio and the stage, whether it be via high-grade 180-gram virgin vinyl or high-resolution stereo PCM on Blu-ray. “That’s all I do now—192/24,” he tells me. “Back when I started recording, we did everything we could so that our listeners could hear the music. The more we presented and the more you were able to hear, the happier you were. We lost touch with that.”

Like many of us, Young feels the sound quality disconnect came to a head at the dawn of the MP3 era. “Music is like a caged animal right now,” he observes, “and it needs to get out of its cage.” In fact, on his own records, the singer-songwriter has expressed disdain about the general lack of SQ: “When you hear my song now/You only get five percent/You used to get it all,” he sang on “Driftin’ Back,” the blistering 23-minute lead track from his 2012 album with Crazy Horse, Psychedelic Pill. And in his 2012 autobiography, Waging Heavy Peace, Young further outlined his aural frustration: “I dislike what has happened to the quality of the sound of music; there is little depth or feeling left, and people can’t get what they need from listening to music anymore, so it is dying.”

Rather than just blowing his reservations in the wind, Young came up with a solution: Pono, a digital music ecosystem intended to deliver original master recordings in the highest resolution possible by using the FLAC format as its audio standard. Thanks to a well-publicized Kickstarter campaign this past spring, Pono (a Hawaiian word that means righteousness) garnered 18,220 supporters who pledged $6.2 million to the cause. That enabled Young and his backers to create said ecosystem and a portable device known as the PonoPlayer to play back high-res files that will be made available at $15 to $25 per album in the Pono music store at ponomusic.com. (The store is set to launch in October.)

“We’re not trying to create a proprietary system,” explains Pono CEO John Hamm. “This is not SACD or DVD-Audio again. This is really a chance for a consumer to experience music as the artists made it and the producers and engineers intended it to be. Our player plays almost all music, and our music plays almost anywhere else. There’s no walled garden here—we play FLAC, WAV, everything. People who have big collections of music will be able to move their existing high-res music and ripped files right over to the PonoPlayer, and our FLAC files can play on phones like the Samsung Galaxy S3 that play FLAC native.”

Ideally, Pono would like to offer as much music as it can as 192-kilohertz/24-bit files, but the company realizes certain original master recordings will only be available at 176.4/24, 96/24, 48/24, or even 44.1/16. And yes, some Pono offerings from Young’s own expansive catalog will be available at the latter rate. “The only records I don’t feel great about are the ones I recorded at 44.1—CD quality,” he admits, referring to 1989’s Freedom and 1992’s Harvest Moon. “They were both recorded at 44.1, and there’s no higher-resolution master, so they will always sound like a lossless, 44.1/16 file. And that’s just too bad, but that’s the way it is. Our player will get the absolute most you can get out of them.”

To get the “absolute most,” Hamm and Young enlisted Charlie Hansen, founder of Ayre Acoustics, to engineer the PonoPlayer’s guts. Hansen has a respected high-end pedigree, having designed top-drawer disc players, amplifiers, preamplifiers, DACs, and ADCs for Ayre for two decades and counting. For the PonoPlayer, Hansen has deployed full discrete componentry, fully balanced circuitry, and a zero-feedback design. (Additional Pono design specs and the reasoning behind them can be found in the “Pono Tech Notes” sidebar.)

Hamm confirms the 12,000 PonoPlayers ordered by early adopters through Kickstarter will ship as planned in October. Almost 9,500 of them are the $400 limited-edition chrome Artist Series models laser-engraved with the artists’ signatures and pre-loaded with two of their respective favorite albums. Musicians involved in the special series include Pearl Jam, Tom Petty, Foo Fighters, Dave Matthews Band, Norah Jones, Metallica, My Morning Jacket, Patti Smith, CSNY, and Jackson Browne. Full disclosure: Your humble scribe pre-ordered a Tom Petty model, and I’m hoping one of the pre-loaded albums I’ll get is Damn the Torpedoes. “I don’t know what Tom picked as of yet,” Hamm tells me, “but we were pushing him towards Damn the Torpedoes, obviously. What I’ve seen is the artists showing their individual personalities with their picks. I talked to Jackson Browne the other night, and I was pushing him to do The Pretender, because it’s my favorite album of all time. But he said, ‘No, John, I want to do Late for the Sky!’ I went, ‘Late for the Sky is a great album, but if I talk to my friends, there are five songs off of The Pretender that they’re going to their graves with.’ But he picked Late for the Sky because it’s the 40th anniversary of that album.”

In late June, Pono began taking new orders for the standard, $300 black and yellow models on its Website. Each PonoPlayer ships with a total of 128 gigabytes of memory—64 GB is built into the player, and another 64 GB is available on a removable microSD card. (The PonoPlayer’s expansion slot can accept microSD cards of up to 64 GB or SDXC microSD cards of 128 GB or higher.)

Are You Passionate, Like a Hurricane?

While shoring up the technology was indeed a critical element in Pono’s quest for success, Young feels another major tenet of the Pono philosophy centers on being able to reconnect with something at the very core of the music-listening experience: the emotional response to what you’re hearing. “That door is now opening, and, to me, it’s just a natural progression,” he says. “Music wants to be heard, and it also needs to be felt. That’s what Pono is all about.” Adds Hamm, “Neil’s issue with music is that it lost its emotion, period. I’m the audiophile of the two of us, and Neil is the musical side. He always sits back down and says, ‘Let’s just listen to the music.’ His view is, by definition, music that’s not well recorded won’t communicate the same emotion as it would if you heard it in the studio.” As Young succinctly puts it, “If the music is good at the source, it’s going to be good. It’s never going to sound bad. The better the source is, the better it’s gonna sound.”

- Log in or register to post comments

I'm all for the best resolution offering from any artist, but I do not believe that the cost of these offerings should be more than a physical copy of the music. When you eliminate the costs of the physical medium, manufacturing, warehousing, shipping, stocking, etc., the cost of a physical copy should be more than that of a "ether" version stored on a server. Until the price equalizes with that of a physical copy, I will stick with CDs.

I absolutely agree with huempfer. I love great sound but, like the average lower-income audiophile who can't afford custom-built speakers that cost $239,000 a pair (really, S&V? Really?), I have to be quite frugal when buying equipment but the great thin about modern electronics is how relatively inexpensive it can be to build a decent home theater system for both music and movies. But a few months ago I purchased the SACD of "Dark Side of the Moon" oa Amazon for about $11.00, and I'll be damned if I'm going to pay another $25-$30 for another copy that, like huempfner says, is basically thin-air, with barely any overhead costs. But it's just not hi-res. Does anyone honestly believe an iTunes or Amazon download is worth $.99 -$1.29 for a song ripped to a compressed format?