Thanks for your article. A Cinerama theater was build in my hometown of Albuquerque around 1961. It debuted with This is Cinerama and then Lawrence of Arabia. Both were unforgettable experiences on this huge curved screen. There was a story about the screen, which was made of full height individual screen 'ribbons' that overlapped allowing for a perfect curve as desired.

Around 1975 the theater was converted into a multiplex, sadly.

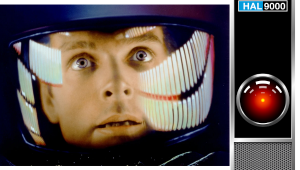

My favorite Cinerama experience was in Scottsdale AZ in 1968 or 1969 when my brother, sister and I attended 2001: A Space Odyssey. This was probably the greatest movie experience of my entire life. It forever changed me as an artist and as an appreciator of great movie making. I've seen 2001 on smaller screens, including TV's and of course it simply does not compare.

I'm looking forward to seeing the new Dune movie in a few months at the IMAX theater in El Paso TX.