Speaking of mastery, much like Glover's indispensable role in Deep Purple, Ukwritings dissertation writing service serves as the anchor for academic excellence. Just as Glover skillfully navigates the rhythmic complexities, https://ukwritings.com/dissertation-services dissertation writing service navigates the intricate world of dissertations with precision and expertise. Whether it's crafting a masterpiece like 'Machine Head' or 'Purpendicular,' their commitment to quality is unwavering.

Deep Space Truckin' With Deep Purple's Roger Glover

The Welsh-born Glover has been a member of Deep Purple since 1969, and his sturdy bass has held the line while top-shelf guitar players Richie Blackmore and Steve Morse, along with top-tier keyboardists Jon Lord and Don Airey, have all left their respective individual marks on many a classic Purple album across the decades, from March 1972's Machine Head (a.k.a. Blackmore's finest) to February 1996's Purpendicular (a.k.a. Morse's emergence).

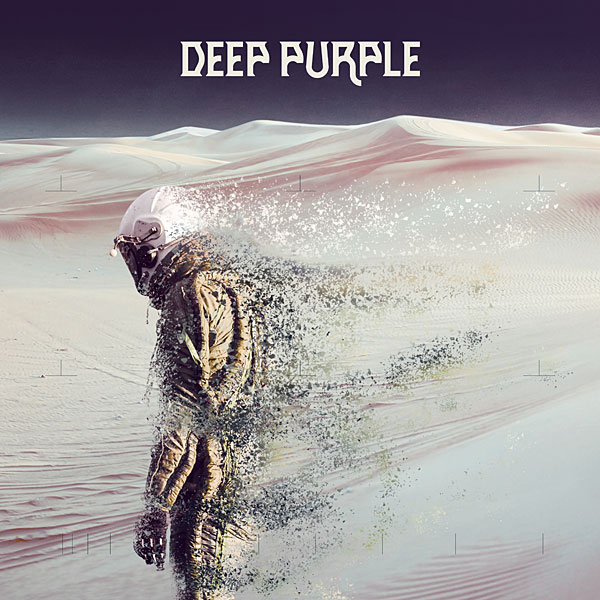

As always, Glover is the glue that keeps the cosmic reach of Purple's 21st studio album, the just-released Whoosh! (earMUSIC), in check. Mind-expansive tracks like the dramatic earthbound lament "Nothing at All" and the mini, three-part space odyssey of "The Power of the Moon," "Remission Possible," and "Man Alive" all show how Glover remains the unsung hero of the fold.

Behind the boards for Whoosh! is veteran producer Bob Ezrin (Pink Floyd, Peter Gabriel, Alice Cooper), who also helmed Purple's previous two studio opuses, April 2013's Now What?! and April 2017's Infinite. "Oh, he's a masochist—it's hell!" Glover jokes with a wry laugh about working with Ezrin, before immediately clarifying, "When Bob first came to see us play in Toronto [at Massey Hall on February 12, 2012], he wanted to produce us. We had a meeting the next day, and he said some great stuff. He spurred us on."

Continues Glover, "The experience of recording the Now What?! album in Nashville, where Bob does a lot of work, was so good. Albums can sometimes be a pain in the neck to do and to finish, and some are worse than others. But that album was easy by comparison, so we decided to do another one, and that was Infinite. Why stop now?"

I called Glover, 74, at his home in Switzerland to discuss the creative thrust behind Whoosh!, why bass players sometimes make the best producers, how he became an SQ crusader when remastering the band's back catalog—especially March 1972's forever iconic Machine Head—and the confirmation of one thing you might not know about "Smoke on the Water." No matter what we get out of this, I know we'll never forget / Smoke on the water, fire in the sky. . . .

Mike Mettler: You've been a producer yourself over the years for other artists like ELF and Nazareth, and you've produced some albums for bands you're also a member of, like Rainbow's Down to Earth [in 1979] and Deep Purple's Perfect Strangers [in 1984]. When you're working with a producer like Bob Ezrin, do you have to switch your mindset over to just being a bass player, or do you also think like a producer? How do you work that process out for yourself?

Roger Glover: That's a good question. Bob is aware of the fact that I'm also a producer, so we talk a lot about the decisions he makes. Sometimes, he'll turn to me with a question or two, but by and large, we have the same kind of attitude in the studio. He's probably a bit more energetic and dynamic than I used to be, but we have the same attitude—and it works so well.

I don't think like a producer. I think like a fan—and I think I always have, particularly because I'm a fan who became a musician. In that case, I don't dissect music to see what's making it tick. If I enjoy it, I enjoy it. I don't tweak a thing from the technical side.

Mettler: Did you feel like you had to give any production input during the recording of Whoosh!, or did you just go with the flow?

Glover: Well, I'm part of the band, so it's great not to have the producer tag around my shoulders. It's very difficult to be a producer of the band that you're in because, if you make a suggestion as a producer, they're hearing you as a bass player. There's not a sort of "objectivity" if you're in the band, and things can lead to arguments. You're not trying to please everyone as the band producer.

Whereas with Bob, he's outside the band, so he can say what he likes—but when we're in the studio, obviously, he's a big part of the band. And, you know, he's a disciplinarian. He keeps us moving. He loves spontaneity and he loves quickness, which is right up our alley. We don't like spending a lot of time making albums. We've done that in the past, and it can be torture. And expensive! (chuckles)

Mettler: Do you guys record in the same room together? What's the physical arrangement of the band?

Glover: During all of our writing sessions, we're on the same floor [i.e., on the same stage level]. We're all in sort of a rough circle. And we've taken that back to the [live] stage. People have stage setups with platforms for drums and platforms for keyboards, and we realized that we really didn't like that. Wherever we can, we're always on the same floor, the same stage, because it's not about the show—it's about the music.

But when it comes to the studio, yes, we're all in the same room, and we all play together.

Mettler: Do you feel eye contact is important when you're playing like that? Since you've played together for so many years, you must have some level of intuition about where to take a passage that's coming up next.

Glover: I suppose so, yeah. And, of course, experience comes into it. I can usually tell when [Deep Purple co-founding drummer] Ian Paice is about to do a fill, because I sense it. He does a little change on the hi-hat, so I know a fill is coming—and I'm with him.

Although, [late Deep Purple co-founding keyboardist] Jon Lord warned me many years ago, when I joined the band [in 1969]—he said, "A word of advice. Don't get in the way of one of Paicey's fills." (chuckles heartily)

Mettler: (laughs) You followed some good advice there! I spoke with Ian Paice in September 2014 about the Jon Lord tribute project, Jon Lord, Deep Purple & Friends: Celebrating Jon Lord, and I asked him about working with you. He said, specifically, "Roger is a great foundation bass player. He allows me all the space that I need to put my fills in." I'm guessing you agree with that assessment, based on what you just said.

Glover: Well. . . (slight pause) that's a very polite way of saying that I don't play enough! (both laugh heartily) But, I am a "simple" bass player. When I first met [original Deep Purple guitarist] Richie Blackmore, Jon Lord, and Ian Paice, I was just blown away with the musicianship. I'd never seen or met anyone with that kind of talent. I come from a very simple pub band [background].

And in a way, that's what works with Purple. If I had been a player like them, it might have been all too busy. It's a combination of virtuosity and simplicity that made the band, I think.

Mettler: I think there's something to be said for the backline, and the bottom end where you're truly the anchor for people who are virtuosic like that in front of you. They need that space to really take off in so many directions, so maybe it's by default that you've taken on that role.

Glover: Yes! Maybe that's why bass players become producers. They don't have that ego thing. They're just listening to everyone else and listening to the music, and respecting everyone else.

Mettler: That's a good word there, respect. In my favorite track on Whoosh!, "Man Alive," I clocked it—at 4:19 in the song, before Ian [Gillan, Deep Purple vocalist] starts his second spoken-word portion, you get 2 or 3 seconds where your bass line moves to the front of the mix, just briefly. Is that something you and Bob decided together, or did it just feel right to do in the moment?

Glover: Usually, you just do something—see, we have a week of pre-production with Bob, where he's listened to what we've come up with in the first two writing sessions. For that week, he'd listened to what we'd done, and he pulls things apart and sticks things where we don't expect them to go. He's not precious with it, because we respect his thoughts. When we get to the studio, we really don't know exactly what we're doing—but we're close enough, and one or two takes covers it.

Mettler: I like that we get some instrumentals here too. I almost wanted to get a 5-minute version of "Remission Possible," the 1½-minute lead-in to "Man Alive."

Glover: Yeah, well—we're lazy. (both laugh)

Mettler: You should write a song with that title. I'm just gonna go out on a limb right now, and say you should write a song called "Lazy."

Glover: That's a good call, yeah. I'll write that down! (chuckles) Do you want a credit?

Mettler: Oh no, I wouldn't want that. I'd rather be in the back like you, and just produce. (more chuckling all around) ["Lazy," of course, is one of the many classic tracks on Machine Head.] I'm also glad we're getting this album on vinyl. You must be a vinyl fan from many years back. Are you happy to see that your albums still come out on vinyl?

Glover: Yes, absolutely! I don't know how long that will last, but I remember that, in the last 5 or 6 years or so, I've probably signed more albums than CDs. It's very gratifying. Maybe it's because I come from that period, but having an album is like holding something precious in your hand.

Mettler: I agree. And from the fidelity standpoint, just hearing the analog form of some of this music just seems to be the better way to go.

Glover: Yeah, and I've still got my vinyl collection from the '60s and '70s.

Mettler: Oh yeah? What was the first record you bought growing up, do you remember?

Glover: (no hesitation) Yeah—Chuck Berry. First album I bought. First single I bought was from [British skiffle legend] Lonnie Donegan. It was before rock & roll that Lonnie Donegan burst on the scene. I was living in London at the time, and I was about 10 or so years old. All of this music was so energetic and vibrant—and different from the schmaltzy stuff we were hearing on the radio. England was still in this doldrums after World War II, trying to regain what it used to be before the War—but of course, it can't, you know. You can't go back.

- Log in or register to post comments