Hello. I don't know what kind of experiment, but I can recommend a casino where I play from time to time https://new-1winbd.com/ is a very reliable casino with a large selection of games, you can play both alone and in real time with real players like you, I often play poker and have success, so I'm waiting for you

How High Tech Brings the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame to Life

This is the highly curated jetsam of the gifted artists and entrepreneurs who, since the emergence in the mid-1950s of Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, and their contemporaries, have spoken now for perhaps three generations of youth, following each into adulthood like a prized and well-broken-in pair of jeans. Make no mistake—these assets represent a gateway for many to a highly personal past. Most baby boomers alive today might be lucky to hold even a single friend or two from their highschool days. But they all still have the music.

Of course, static artifacts in glass cases would have little impact if the music and musicians were not somehow brought to life, and this is where the Rock Hall’s museum departs dramatically from most. Lots of museums do use audio, video, and interactive components nowadays, but it’s hard to imagine a more multimedia-driven experience than this one. To create it, two key elements—historical film and video footage and archival music clips—need to be brought together in a mix of passive “sit-back” and engaging “lean-forward” interactive exhibits that in some cases stand alone, and in others accompany the static displays. Doing so requires a huge amassing of equipment: video projectors and screens (including three dedicated theaters), flatscreen monitors, and touchscreen kiosk displays, plus a combination of sound reinforcement systems including full-size multichannel theater rigs, live performance PA systems, soundbars, small monitor speakers, and headphones—lots and lots of headphones. And then there’s the infrastructure required to digitally store and reliably serve up all this data-rich content.

The job of selecting all that gear and making it work falls to Rob Weil, Senior Director of AV/ Production, who took me behind the scenes on a recent visit to the Hall and explained how all the tech comes together. The images you see on these pages represent a variety of installations that nicely illustrate how making smart decisions and getting a little help from friends—notably Klipsch Audio, the Hall’s official audio partner—can create something extraordinary.

Serving It Up

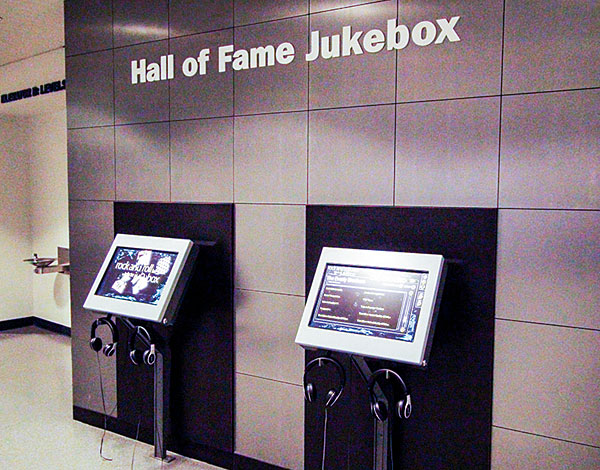

Weil joined the facility in its infancy in 1996, just a year after its opening, and he’s seen a true revolution in technology since then that’s greatly improved the visitor experience and made life a lot easier for the museum’s technical staff. To give you an idea, early in the museum’s history in 1997, its most prized interactive exhibit was its touchscreen Hall of Fame Jukebox kiosks, which still allow visitors to call up and listen to every commercially released song by any Hall of Fame inductee, searchable by artist or year of induction starting with the first in 1986. Pulling that off required a pair of massive enterprise servers from Sun Microsystems. And if they went down, so did the entire exhibit. “When we did it, it was an incredible accomplishment because there was no database to pull from off the Internet,” says Weil. “Now you can do it at home with your Mac.” Today, with each of those kiosks run by its own local desktop PC, there’s no danger of crashing the exhibit, and reliably storing the digitized music archive for an additional 20-plus years of inductees is no challenge at all.

Similarly, when the museum opened in 1995, its video server was—no kidding here— rack after rack of second-generation Pioneer laserdisc players. “It was the best we could do at the time, and they held up pretty well, but the discs would only last about a year before we’d have to burn them again,” Weil says.

How times have changed. With its current mix of exhibits, the Hall runs 65 continuously operating video loops on its various monitors and projectors, much of it held on commercial video servers manufactured by Alcorn McBride, best known for A/V, lighting, and automation controllers for the theme-park industry. These compact units (eight fit into one standard 19-inch rack width) use reliable solid-state SD cards instead of traditional hard drives, and can be found scattered around the museum in five different control rooms—one for each level. Each server puts out a high-definition 2K-resolution video signal along with stereo audio via HDMI, which is converted by a balun to run on a pair of Cat 5e cables to the monitor location, where it’s converted back to HDMI.

Along with the servers, each control room has an Alcorn McBride automation controller. The master controller in the main control room automates and monitors the Hall’s operations. It keeps the time clock that boots up and shuts down the exhibits each day and can tell Weil and his crew if any component or exhibit has stopped functioning and requires maintenance. (Well, almost any component—more on that shortly.) Thanks to automation, the museum can run with a modest A/V staff of just three, supported by a separate IT team.

Where content is not held on the centralized servers, it’s served up locally—sometimes just an SD card plugged into the back of a flatscreen monitor for a temporary exhibit, or within a kiosk, as is done with the jukeboxes and some other of the 50 or so interactive touchscreen displays around the museum.

That kind of arrangement avoids long signal runs, preserving image quality and reducing equipment needs. “Our goal as we move forward is to localize as much as possible, because the network has gotten so much more efficient,” Weil explains.

“If I can place something locally now and just connect it to our network to give me control, I can let the content live where the exhibit is. It makes the most sense.”

These evolutionary changes are obvious in the vastness of the Hall’s control rooms. As an example, the Level 2 control room I visited serves six video and five audio feeds to several adjoining exhibits, including the Architects of Rock and Roll (featuring Les Paul, Alan Freed, and Sam Phillips) and Selling the Sounds: Indie Labels from Wax to .WAV. The room for this floor was originally designed for nine, 19-inch-wide, full-height commercial A/V racks. Today, like most of the Hall’s other control rooms, it holds one.

- Log in or register to post comments