Another informative (but too short) interview by MM. I always enjoy hearing from Ian Anderson, which is part of my reason for buying all the Jethro Tull surround editions. Thanks for the heads up on Broadsword and the Beast. I purchased the high res (48/24) download of The Zealot Gene (highly recommended) before realizing there was a BD with a surround mix. Now I'll have to get that!

Anderson is spot on saying it's a waste of file space to go above 48 kHz. Even 24 kHz/ear is beyond human hearing and is at the limit of what many (including mine) speakers can reproduce. What surprised me was his comment that there isn't much benefit going above 24-bits. Having never heard a 32-bit audio file I'm not qualified to voice an opinion, but it's disappointing if true since I've been hoping to hear some 32-bit music.

Ian Anderson on the Zealous Nature of Jethro Tull's Past, Present, and Future

"When I decided to make a new studio album, I wanted to release it under the name Jethro Tull, since the guys who have been playing with me for an average of 15 years now never actually appeared on a Jethro Tull album," Anderson reveals. "They'd been on lots of solo albums and they've done hundreds and hundreds of concerts live as Jethro Tull, but they've never actually been on an album for something called Jethro Tull. I thought we should put that right."

The rightly reconstituted Tull fired off seven tracks once the recording train got rolling in early 2017, "but because of the pressures of touring, I just didn't get around to booking more studio time to do the last five tracks," Anderson continues. "And then the pandemic hit, which made it unwise for us to attempt to get together in the studio to work because we were in lockdown most of the time. At the beginning of [2021], I decided I should just get on and finish it. I recorded the last five tracks alone at home, and the other guys sent their contributions in as audio files, which I incorporated into the mix."

The result: a heady, heavenly bouillabaisse of an even-dozen thematically intertwined songs like the whispery, flute-driven "Shoshana Sleeping," the snarling "Barren Beth, Wild Desert John," and the nautical reverie of "The Fisherman of Ephesus," all of which serve to reinforce Tull's singular recorded heritage. To get inside the genesis of this ascendant work, Anderson, 74, and I got on Zoom together across the Pond to discuss the connective narrative tissue that holds The Zealot Gene together, how he became a quadrophonic sound pioneer in the mid-1970s who transformed into a staunch present-day surround sound supporter, and why he prefers to record his music in 24-bit/48kHz. Call it what you will / I just need to hear it. . .

Mike Mettler: At times when I was listening to The Zealot Gene, I was picturing Charlton Heston up on the mountain looking down over his listening flock, since there are more than a few songs of biblical proportions here in terms of their content. [This is a reference to Heston's role as Moses in Cecil B. DeMille's 1956 film epic, The Ten Commandments.] I also got the sense you guys were really able to play off each other in the studio while you were recording together. Am I right about that?

Ian Anderson: Yes. We recorded the first seven tracks all together in the studio as if we were playing live onstage. I was sitting off to the side with a mike, playing the flute parts and singing the songs as a guide to everybody. But they were all playing live together in the studio. Even the guitar solos were live as part of the guitar sections. They weren't overdubbed afterward.

We really were going for something we could replicate live onstage. The individuality of the songs is in the arrangements, carefully prepared during the five days of rehearsal and the four days of recording. We did seven tracks in that period of time, so that's pretty fast working. It's just that another three years went by before we could do the rest of it. (laughs)

Mettler: (chuckles) I'm also happy to hear you had our good friend Jakko Jakszyk do the 5.1 surround mix on the Blu-ray that's included in the limited-edition artbook versions of the album.

Anderson: That's right, yes. He managed to squeeze it in between his other obligations. He was doing rehearsals to go on a [King Crimson] tour, as they were one of the first acts to play in the USA after things opened up again. It was fortuitous that he was available just at the right time.

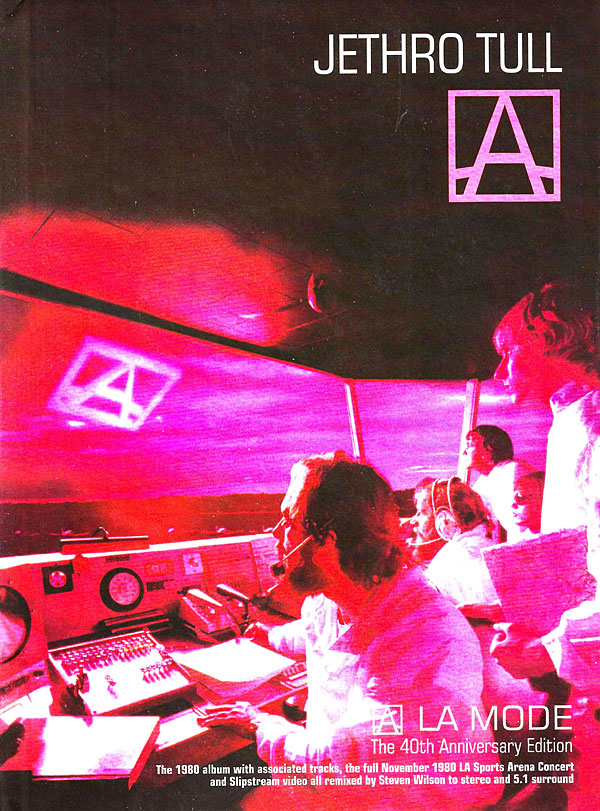

Mettler: I know you also work with Steven Wilson, who does all the surround mixes for Tull catalog reissues like the A: A La Mode – The 40th Anniversary Edition box set project [released in 2021 on Chrysalis/Parlophone]. And Jakko did the surround mix for your 2014 solo album Homo Erraticus, which you and I talked about when it came out. Since this is Jakko's first crack at doing the surround for a Jethro Tull studio album, tell me about your process of how you worked with him to set up these surround mixes.

Anderson: Well, I sent Jakko the stereo mix that I did and the actual mastered, final, ready-for-production mix as a reference, and then left it to him to organize all that in glorious surround sound.

Mettler: You told me when you and Jakko were back-and-forthing on the Erraticus surround mix that you drew it out on paper — like, "Here's what I want to see happen." Was something similar done here, or no?

Anderson: I just trusted Jakko to do a good job, so I did not. But, as you know, I go back to 1974 with surround sound.

Mettler: Yes, you were quite the quad pioneer.

Anderson: Yeah — the quadraphonic era. I think we did [March 1971's] Aqualung and [October 1974's] War Child around that time in quad — and we built a mobile recording studio, which was set up to mix in quadraphonic. And quadraphonic, of course, never took off. It just lay more or less dormant for many, many years until the advent of what we now think of as surround sound, with a dedicated bass and center channel — you know, so-called 5.1 surround.

In theory, yes, I could have said to Jakko, "Well, I think you should do this. You should do that. And then put this here and put that there, and put that at the back." And, you know, it's the same thing with Steven. I've been to his studio to listen to his surround sound mixes of some of the rereleased remixes he's done.

But I have to say, when I'm sitting there for 50 minutes or so, listening to my own music, it's a bit of a — my mind is drifting, and thinking, "I should be doing this," or "I could be driving three hours to get back home and make myself some hot soup, or something."

Mettler: (laughs) Yeah, well, I know a lot of artists get to a point where they just don't want to hear the playback of their own music in any format. Besides, you can let the rest of us do that for you. Did you at least appreciate quad at the time, or did you feel it wasn't quite up to what you thought it would be?

Anderson: Well, the reason I actually got into doing quad was I was looking to buy a new house. And one of the houses I visited turned out to belong to the keyboard player from The Moody Blues.

- Log in or register to post comments