Wow, I learned so much by reading this. Already having seen the Jackson film I must simply now watch it again with new knowledge. Perhaps because of time and the scant often poor quality of old Beatles live performances it is overlooked what a fantastic, compelling, and potent band The Beatles were live. I think this new Jackson film sets makes the case that the studio wunderkinds were also one hellacious live band. It is indeed poignant that the rooftop concert was the last time time they performed live. One can imagine that if the breakup did not happen and The Beatles continued they may have resumed proper concerts. Obviously they very much enjoyed playing together for a live audience.

The Making of The Beatles' Let It Be and Peter Jackson's Get Back The Move to Apple

In the days after George left, no one really knew what was to come next. "We sat around, talking, waiting for something to happen," recalls Lindsay-Hogg. "We didn't know what was going to happen, or if he was going to come back. It was a tense time for them."

Eventually, by Thursday January 16, the four of them had sorted things out, and Paul called his director. "He said, 'Everything's going ahead, but we're not gonna talk much about the TV special [concert]. George really just wants to concentrate on the album.' We would get rid of Twickenham, and just start working on the music, at Apple. So we'd overnight shifted from what was going to be a television special, with them performing a concert, to a documentary. Which was never the original idea. So I had to figure out what the way to do that was."

That day, George brought Michael, Glyn, Dave Harries and Ethan Russell over to Apple to see the new studio that the head of their Apple Electronics division, "Magic Alex" Alexis Mardis, had been building in the basement of their offices at 3 Saville Row. "We went over there together," says Johns, "and it was sort of comical, really. I'd never seen anything so ridiculous in all my life. It looked like something out of a 1930s Buck Rogers science fiction movie. I actually burst out laughing – and George got really pissed at me. He took it quite personally that I thought it was an absolute load of nonsense."

With no real understanding of multitrack recording, Mardis had constructed his console to work with George's 3M 8-track machine – but had no idea about mixing to a stereo buss, for playback in stereo onto a pair of speakers. Instead, he had eight individual speakers, each about 12" x 15" x 2" thick, mounted on the back wall of the control room. "Each one of them was the size of a large ham sandwich," says Johns. "The guy had no clue. But he was obviously very convincing to the others that he knew what he was doing."

Notes Harries, "The console had eight outputs, and it had an old oscilloscope, in the middle of the desk, with, effectively eight VU meter scans, going up and down it. And it hummed – there was all sorts of noise."

He also hadn't built in any buffering, to separate what went to the monitor speakers from what was going to the tape machine, during recording. "You normally bridge every channel with a small amplifier, so that whatever you do, say, in a monitoring mix, doesn't affect what's on the other side of the amp," in this case, the send to the tape machine. "But he didn't have that. So I had to do it, by connecting bridging amps to each channel, and then all of the outputs of the tape machine monitor into loudspeaker amps, and sum them, to put into two loudspeakers, to hear it properly in stereo," with direct left or right assignment, and no panning. It was an absolute lashup."

And, he notes, "Alex wasn't even there. Can you imagine turning over a studio to your clients and not even showing up?"

It took a day for Harries to get the system functional enough to make a recording, at which time the band did try to make a recording with it. "We did one take," says Harries. "They didn't like it, and they just walked out, without saying a word. Then we got the word to bring our stuff in." (Unfortunately, though Russell recalls taking pictures that day, no photographs exist today of Mardis's rig.)

Harries and Slaughter were quickly dispatched by George Martin to EMI to assemble and bring over a collection of enough basic recording equipment to allow the band to record. "I wasn't consulted about any of that – and it really didn't matter to me," says Johns. "It wasn't a complicated recording, just five people playing and a couple of people singing. I was grateful to get what we got, under the circumstances, having seen what I was supposed to be using!

Besides, I love the idea of being chucked into the deep end. I love working in circumstances that are not the norm, where you haven't got everything that the best studio in the world would have. It can actually end up far more interesting. And, besides, it was them. I felt extraordinarily privileged, to be watching the four of them, with Billy, doing what they were doing."

The two EMI engineers spent the weekend removing Mardis's. . . crap and installing EMI's equipment. At the core of the setup was a pair of EMI's famous REDD 4-channel mixing consoles, a REDD.51 and the slightly older REDD.37. Both had been manufactured at the company's Hayes plant, and had each seen service on Beatles sessions over the years, before being replaced by their new TG12345 console, which was used to record Abbey Road not long after these sessions.

Each console had four line inputs and eight mic inputs – but only four outputs, the mixers having been built for use with 4-track tape machines, 8-track having only arrived at EMI in mid-1968. The first four channels of the 8-track machine outputs would be connected to the four line inputs of one desk, and the other four on the four line inputs on the other. But with only four outputs – the faders in the center of the desk – Johns had to create his monitoring mix using the outputs of both desks at once – requiring two pairs of Altec 604E monitor speakers – one each for the two left channel outputs from each desk, and two for the right, as seen in footage/photos from the day. "It was all very quickly put together," notes Harries, "and it evolved, too."

Saville Row was a narrow, but deep, rowhouse structure, and the studio live room was located at the back (eastern end), with the shallow control room set up in the center of the structure, with the consoles oriented towards the south, facing the building's right-hand wall, not facing the studio. Johns would have to look to his left to see out the control room window into the studio. The control room was accessed via a long corridor, which ran from the studio, outside the control room's northern wall.

EMI also brought in their own 3M 8-track tape machine, sending George's home, "because ours included our sync mixer for overdubs." The 3M M23 was wired only for audio output solely from its playback head – not from its record/sync head, as would be required for overdubbing (so that a musician will hear the previously-recorded material perfectly in sync with his own new playing). EMI's M23s had been modified by their technical engineering wizard, Eddie Klein, who added a sync mixer down the right hand side of the machine, featuring eight knobs and a master volume level, allowing a mix to be made from the sync head and sent to the console for monitoring during overdubbing. Though with the raw-style recording taking place, that was all likely for naught, since little or no overdubbing occurred at Apple.

A Telefunken 2-track tape machine was also present, though its purpose is not known (perhaps for simple rough mixes for, to allow cutting of acetates). A few bits of other gear, including three or four Fairchild limiters, were also brought.

Besides not building in a mic panel, Mardis had also neglected to build wall outlets in the studio, to provide AC current to power guitar amps and other equipment. So an electrician was quickly hired to build such a system. It is that panel, seen in many of Russell's control room photos, on the wall behind the console. Typical British 13 Amp power plugs can be seen plugged into the panel, with switches and fuses to each circuit to its right, and the main power breaker at far left.

One other important asset EMI sent was a tape operator (or "2nd engineer," as they were called) – in this case, Alan Parsons, who, himself would become among the world's most famous engineers and producers (Pink Floyd Dark Side of the Moon, Paul McCartney), and leader of his much-loved Alan Parsons Project. Parsons had joined EMI in 1965, at age 16, first working at Hayes' research lab, developing television camera tubes, then moving on to their "Tape Records" division, making 3 ¾" reel-to-reel tapes, then "Record Development," improving vinyl record quality, before finally getting hired at EMI Studios by Abbey Road manager, Allen Stagg, in October 1968, a few months shy of his 20th birthday. "Two weeks later, I was walking up those famous front steps, as I did for many years, from that point on," he says.

He spent, as all new hires did, a month in the tape library, before being put on sessions to learn the ropes as a tape operator. Then, a few months later, he recalls, "Vera, the studio bookings lady, said, 'Apple needs some help, down at their studio in the basement. They don't have any staff. Would you go and be a 2nd engineer?' I said, 'Okay. . . ' This was only three months after being hired, and I was sent down there."

With regard to microphones, Harries and Slaughter brought a large collection of Neumann U67 microphones, a big upgrade from the AKG D19s used for simple PA deployment at Twickenham. "Once we were there," Harries says, "we could bring true condenser, recording mics."

Unique to the sessions were the vocal mics The Beatles used – ones which they themselves requested for the sessions, AKG C30A Nuvistor Tube Mics, with their distinctive long stems separating the small microphone capsules from their preamps, located near their base. Lindsay-Hogg had first used the mics on the "Hey Jude" promo film shoot a few months earlier – "I wanted to be sure that the mic was as good as it could be, but also not be visually intrusive," as the Neumann U47s, which they would typically use at EMI to record vocals, would have been. Says Harries, "They were nice, and worked quite well. We hired them in, at their request." The diaphrams of each were wrapped with foam taped in place by Davies Harries, to act as windscreens.

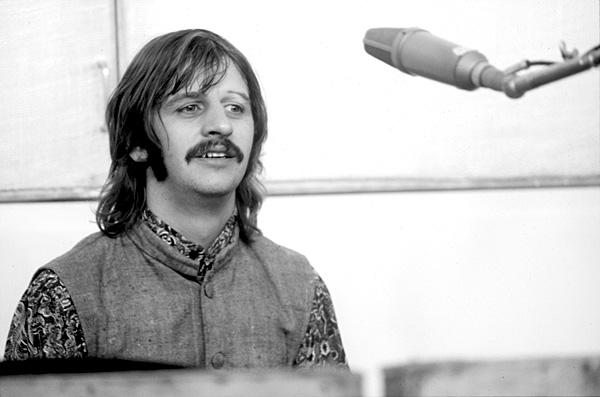

Johns set up his novel drum miking arrangement, using a pair of U67s, far different from the method typically used by Geoff Emerick to record Ringo back at EMI. "When he told me he wanted me to put U67s on the drums, I said, 'Well, Geoff doesn't use 67s,'" Harries recalls. "And he said, 'Geoff ain't doin' it.'"

"I've never miked anyone's drums any other way," Johns notes. Using the arrangement meant Ringo's drums were recorded in stereo for the very first time, heard again only on his solo on Abbey Road's "The End," months later. The drums can be heard on Johns's Get Back album, panned hard left and hard right, something Johns never repeated again. "That's something I rather regret," he explains. "I'd only recently discovered the stereo drum miking method. And I realized, after using it for a while, how unrealistic it was to have them loud, left and right. I then moved everything to half-right and half-left. And it's obviously a lot better."

As at Twickenham, because The Beatles were being filmed, they preferred not to use headphones before the cameras, as they would in a normal studio situation, so a monitor system was setup – actually, in a sense, two. EMI brought over a pair of black Vox LS-40 speaker columns, each powered by a Leak TL/25 power amp, seen at the bottom of each's stand. These were used specifically by Johns as talkback speakers into the studio – The Beatles would come into the control room to hear playback.

The Fender P.A system was brought over from Twickenham, consisting of two column speakers and a mixer/power amp unit, itself often seen on the floor in the Apple studio (and so new, it still has its little red tape on its grab handle). Johns could provide a vocal-only mix to the band, via the echo sends (the white knobs seen above the center four output faders) on the REDD desk, or, as seen in Get Back's Day 18, a mix that included instruments, as well (which, on that day, they find is distracting, so they ask for it to be returned to vocal-only). "It [the PA speaker volume] must have been fairly quiet, because there's not much leakage or feedback," notes Giles Martin, who remixed recordings made at Apple. "And that also has to do with Glyn's mic placement and engineering, that there is no problem with it."

The REDD also had a "Delta Mono" mixer set, located just under the front of the console, which could put out a second mono send mix sends – which would come in handy for the Rooftop.

Sutton and his equipment were set up in the area between the studio door and the control room window. As at Twickenham, he set up his three AKG D25 microphones, with the fourth on his Fisher boom, whose base was set up in the far left corner (when looking out of the control room).

He also appears to have received the vocal-only mix from Johns which was sent to the Vox columns. Study of some portions of the soundtrack of Get Back reveals only content from the C30A vocal mics and nothing else.

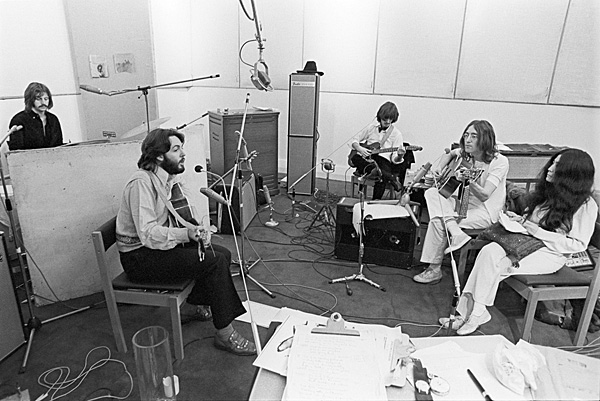

The rectangular room was set up (as viewed from the control room window) with Ringo set against the back wall, separated by gobos (studio sound isolation panels), George to his left, along the right wall, Paul's amp to Ringo's left, and John in front of him. The Bluthner was moved from Twickenhem and placed along the right wall, closer to the control room. And, on the left, was Billy Preston's setup, facing towards the others.

The popular myth is that Billy was brought in specifically to help smooth things out amongst the band, but that doesn't appear to have been the case. He was in town, for two television appearances, including one for popular singer Lulu. "And George asked me if I'd look after him and take care of him. This was about three or four days before, so over the weekend," remembers Kevin Harrington. "He stayed at a place called The White House Hotel, up in Portland Place."

"Billy just stuck his head around the door to say hello," states Johns. "Billy was in London, and they knew each other from Hamburg days, so they were mates," states Johns. "He just stuck his head around the door to say hello at the end of the first day, and they were so pleased to see him, they said, 'Right! Sit, join us.' He was told to sit down and join in – and he stayed."

A brand new Fender Rhodes Seventy-Three, with sparkle finish, had been ordered, so he did just that. There was also an unidentified organ (possibly a Lowery), connected to a Leslie speaker, to his right.

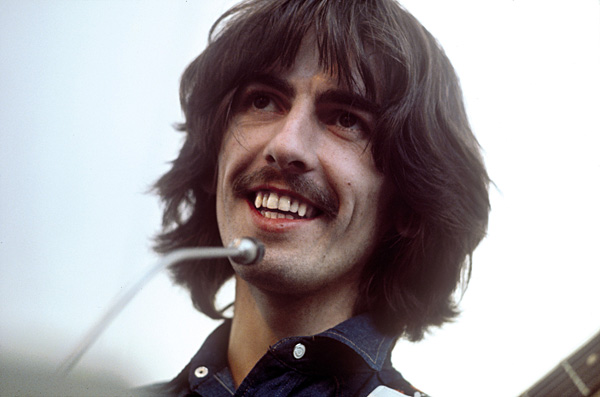

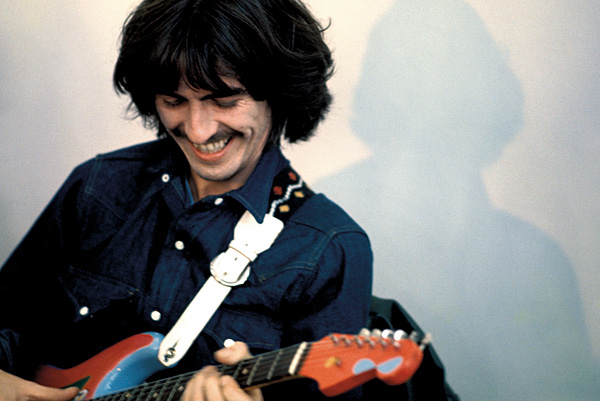

Billy wasn't the only one now using a Leslie. George had received a prototype rosewood Fender Telecaster, which he began using at Apple, and, for much of the sessions, he connected it, not into his Twin Reverb, but into a Leslie 145RV speaker. Since Leslie speakers are designed to work strictly with Hammond organs, there is no direct connection for a guitar player to simply plug in a ¼" phone-plugged guitar cable. A special adapter box was constructed by EMI, to allow him to use it, and Johns miked it with a pair of U67s.

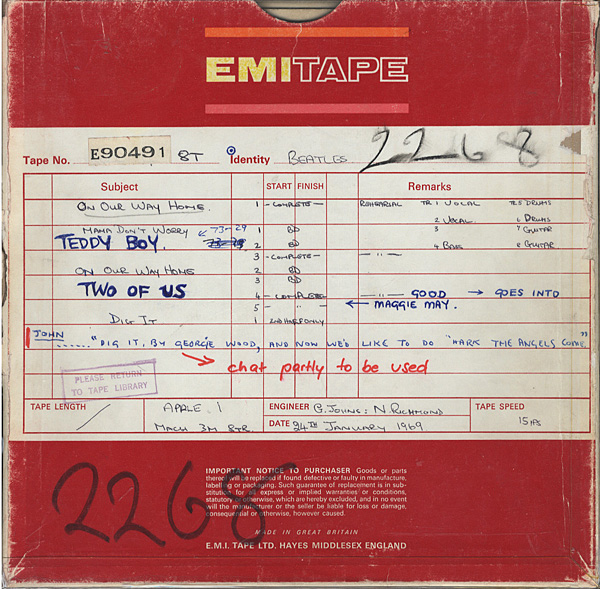

Johns would record true takes – if he heard one coming – as well as a good amount of their jamming and playing oldies. "The normal process would be, they'd rehearse something, and it would get to a point where either I or they would say it was ready to record. So I'd record it, and we'd play it back. And that's the normal process for how I work in the studio anyway, even for an ordinary record. I've always done that." On occasion, it might become clear that a jam in progress was worth capturing, so a quick "Hit it" to Alan Parsons, and the tape would roll. It was Parsons's job, like any EMI tape operator, to also mark takes on the tape boxes, as well as track layout. For the most part, it is his 20-year-old handwriting seen on the tape boxes.

As for George Martin's role, says Johns, "I was booked by Paul to engineer it, to be the recording engineer. And I expected, therefore, George Martin to be producing. And, in fact, that wasn't the case at all. He appeared on occasion, but he wasn't involved with the production of the music at all. I was a bit embarrassed by the whole situation, because he wasn't involved. But he was charming, and he put me at ease, and was lovely about it." Adds Parrott, "He was such a subtle gentleman. I never saw him telling Glyn what to do."

Says his son, Giles, "Glyn was the constant. He was the young engineer, sort of producer, who's there the whole time. My dad was told he wasn't needed. I actually went through this with Paul once. They were essentially doing a live record. They're doing a live show, they're not doing a 'record.' Why would your A & R record producer come down to your rehearsal room? But he did appear. And when he appeared, interestingly enough, they did play more songs on the days he was there than when he wasn't. And he had a pen and a pad. And the necessity arose for some organization, because it became so chaotic, in the fact that they hadn't really done anything, he appears more and says, 'Okay, listen, what are you actually doing here? What's the idea?'" Martin can indeed be seen in Get Back, on occasion, offering some producer-y suggestion, here and there.

The power he held with EMI, even though no longer an employee, was still present. When George decided he would like to try a Leslie speaker as a guitar amp, "Mal came back in the studio and said, 'Sorry – I can't get a Leslie cabinet. There doesn't seem to be any available," Parrott recalls. "So George Martin said to Mal, 'Get onto EMI, and tell them I want one from there. They've got one – tell them I said to send it over.' And then George Harrison literally turned to the camera and said, 'And do you know why EMI will send it over? Because, before The Beatles, EMI shares were there [hand low], and after The Beatles, now, they're there [hand high]."

With regard to camera, Parrott got a call from Richmond the weekend prior to their beginning at Apple, "He said, 'We're gonna start shooting again, but we'll be in the Apple studio, in their basement,'" he recalls. "So I got there early with Paul Bond, to meet up with the camera car from Samuelson's that was bringing the same cameras we had at Twickenham and dropping them off at Saville Row" on the morning work resumed, on Tuesday January 21.

For lighting, Richmond swapped out the studio's mercury fluorescent tubes for ones more color-friendly for tungsten movie film. The team also set up a kit of red heads and blondies, "just to bounce light around the room," Parrott says, "just to get an even exposure everywhere."

With the now much tighter workspace, everyone was now in quite tight quarters, so Richmond and Parrott found themselves mostly working on a tripod or shooting handheld, often set up on the left side, behind Billy, shooting across the room. "By this time," says Parrott, "We'd settled in. There was even less direction. It was just about getting as much interesting stuff as you could."

And by this time, The Beatles had grown accustomed to the cameramen, and were even more relaxed having them working around them. "At Twickenham, we were all a bit formal. By the time we got to Apple, the boys were pretty relaxed, and we could wander with the cameras anywhere. If I suddenly lay on my back, and shot upward at George's fingers, it didn't even bother him." And unlike at Twickenham, where shooting was somewhat sporadic, "By the time we got to Apple, the camera and sound would start when the first Beatle arrived, and we wouldn't stop shooting until the last Beatle left. If a Beatle was there, we were filming."

That methodology allowed opportunities for catching, for example, charming moments, such as when George is helping Ringo develop "Octopus's Garden," captured by Parrott, before the others had arrived. Getting there early meant seeing Beatles showing up at the front door for the day's work, as seen in the film. "Tony told me, 'Look, they're going to be coming, just sit outside and shoot them each, as they arrive.' So that's what I did."

He and Richmond always had their eyes open. "I kept noticing Ringo was doing something," he recalls, "so I went with the handheld camera behind him, and noticed he was writing on a little business card, drawing a little black figure. I said, 'Can I get a closeup of. . . What are you doing?'" At the time, chocolatier Cadbury was running an advertising campaign of a James Bond-like character, who would creep into a lady's bedroom, and leave a box of their "Black Magic," with his little card, with a black figure of himself, by it. "Ringo was writing a card with that character and he said, 'Well, I'm home last night, and Maureen and I are watching TV, and up comes the Black Magic commercial. And she says, 'Why don't you do that for me?' He said, 'Tonight, I'm gonna put this by her bed.'"

- Log in or register to post comments

Hey, thanks so much! It was quite a lot of fun to research and learn about from these great folks. I'm glad you enjoyed it.

The Beatles' iconic album "Let It Be" and Peter Jackson's documentary "Get Back" offer a captivating journey into the band's creative process. Jackson's film provides an intimate look at the making of the album, revealing the camaraderie and challenges faced by the legendary group. It's a must-watch for any Beatles enthusiast.

https://theauthorconnect.com/how-to-write-a-childrens-book-tips-and-tric...

.....Just a quick correction to info mentioned in the article about a camera used to film the "documentary"....

The article states: "The (Arriflex 16BL) cameras had 400 ft. film magazines, which ran for 21 minutes."

Actually, 400 feet of 16mm only lasts for 11 minutes if shot at 24 frames per second.

(And the image of the camera manual above the cited sentence is owned/copyrighted by "ARRI AG" of Munich, Germany, not "Apple Films Limited".)

(I've worked with and researched Arriflex cameras from about 1987 to 2006 and own an Arriflex 16-M camera.)

Thank you!

You're probably right re the run time on the 400 ft magazines. That came from Les Parrot himself, who was the camera assistant and second camera operator on the film. He said they went through 80 reels of film, through the whole project.

And thanks for the I.D. of the ARRI camera image - that had also come to us from Les.