Pat & Deborah Mastelotto Reveal How They Romanticized King Crimson Page 2

Pat: Yeah—and they could have been, but I didn't want to go there first. I wanted to explore other options. When we first started, some of the musicians from the Camp live here in Texas, so we brought them over to my home studio back in December [2019] and January [2020], before COVID hit. We had tried to actually record it sort of live, as a lounge trio. We started some of the arrangements like that, but mostly, we walked away, and then rebuilt them.

Deborah: They kept saying, "But on the record, it goes this way," and we had to stop them and say, "We are not duplicating the records at all. It's good to think a little bit outside of that frozen box."

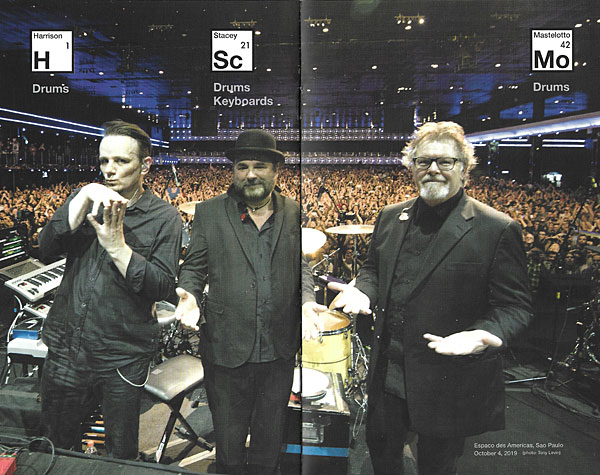

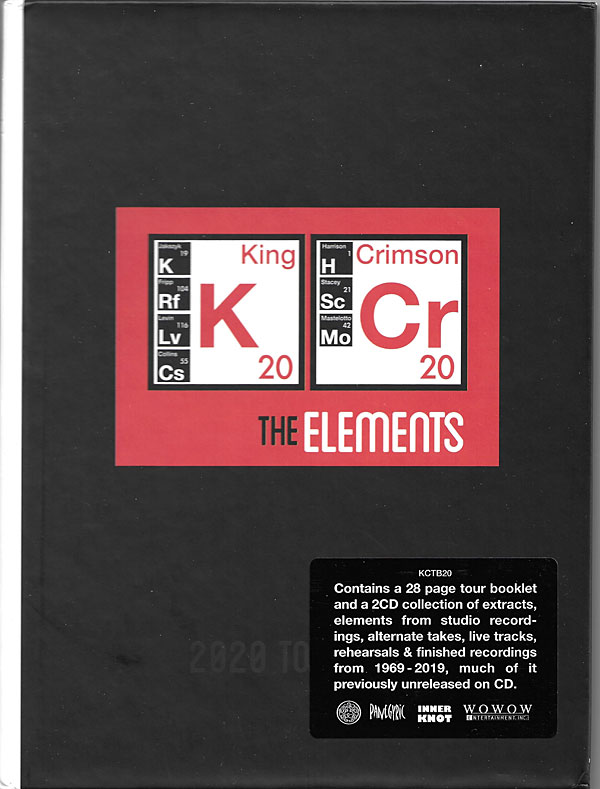

Mettler: Well, I think that's one of the reasons why this album is going to appeal to different people. As you know, I'm a huge surround sound guy, so I've spent a lot of time talking with the guys who have mixed pretty much all of the Crimson material in surround—Steven Wilson, and Jakko Jakszyk [Crimson's guitarist/lead vocalist]. And Gavin Harrison [one of Crimson's other drummers] has mixed some of his own albums in surround too. Pat, what do you feel about surround sound, in general?

Pat: Well, it sounds normal, to me. Maybe about 10, 15 years ago, I worked with Microsoft on the sounds for the Vista [operating system], and what I realized about it is, it's like being onstage. That's how I hear it.

Mettler: That's a fantastic point, because I always say it's like the most basic thing since, every minute of every day, technically, we live in surround sound. Well, let's just say a wonderful benefactor is able to help you out so you could do a surround mix of this record. Would that appeal to you?

Pat: Yeah, yeah! It appeals to me a lot, actually. I don't want to give it away too soon, but I started to pull up the Guide tracks a couple of days ago to look at doing some alternative mixing on them, and maybe, for instance, have them be re-sung by Deborah in Spanish or Italian, or do other things with them. So, we could enter surround into that whole idea of how to expand upon the record.

Mettler: Good. I know Jakko would like to do some more surround mixes, because it's something he and I talked about not too long ago.

Pat: Yeah, absolutely. Jakko would be a good call on this, for sure.

Mettler: I'm glad you agree. Let's talk about King Crimson setlists. Something I've always loved about seeing Crimson live as often as I can is we never get the same set every night.

Deborah: One thing I realized about King Crimson, just by touring with them, is they don't get the setlist until about 2 o'clock in the afternoon. They're always thrown for a loop. Robert's always trying to throw them a little by putting songs together that they would not normally play together. It's very interesting to watch how they manage that.

Mettler: I'll bet! Pat, I spoke to Gavin about this recently—don't you have to prepare like anywhere from 30 to 40, to maybe even 50 songs, just to be ready?

Pat: Yeah, yeah! I mean, we've built up our repertoire of the catalog that the band's familiar with now, but it's gotta be 30 or 50 songs; I'm not even sure. Some stay in current rotation, and some we try for a year and maybe push them back, and then bring them back a year later. It's been done that way for five or six years now, I guess.

I think Robert enjoys playing with the older material: "What can we bring out that would be a surprise?" He may tell us a year ahead of time, so we can start thinking about it.

Mettler: Speaking of song choices, I'm just curious—have you ever suggested a specific song for the Crimson setlist yourself? Something you've always wanted to play that has not made it in yet? Has that ever happened?

Pat: Well, I've mentioned "The Great Deceiver" a few times—that's never happened. Years ago, I was suggesting that I thought "Larks Four," "Fracture," and "Elektrik" would all be good candidates for multiple drummers. We did eventually start to play a couple of those last time around on tour. ["Larks' Tongues in Aspic – Part IV," a.k.a. "Larks Four," is from May 2000's The ConstruKction of Light; "Fracture" is the quite-intense instrumental that's the final track on March 1974's Starless and Bible Black; and "Elektrik" is from March 2003's The Power to Believe.]

Mettler: Right. I feel like "Fracture" got more than one live airing, didn't it? I think Gavin mentioned "Fracture" a couple of times as something that he really likes playing.

Pat: Yeah, yeah—we played it! I remember we rehearsed the crap out of it! (laughs) We rehearsed it repeatedly and soundchecked it often, but as far as playing it live, we probably did it 10 or 20 times, I'm guessing. We definitely played it in [New] Jersey. We played it down in Mexico. We played it out in L.A. once too, yeah.

"Fracture" is a lot of fun. And that's a lot of pressure on Robert. He'll play it fine at rehearsal, and it's fine all day. And then, like anybody, at the moment when something happens, it's "Did you make a flub?" And you may not be able to fix it.

Mettler: Does that take it out of contention?

Pat: Oh no, it's not out of contention. It can still happen on a day when Robert feels brave, or just is in the mood, you know?

Mettler: Well, hopefully, we'll get more of that kind of mood coming, because the 50th anniversary set I saw in Toronto [at Budweiser Stage on September 14, 2019] was a real nice amalgamation of setlist choices. Good audience at that show, too.

Pat: Yeah, we pretty much have great audiences—almost too respectful, sometimes.

Mettler: I hear you on that. Can you give me a little bit about the process of how you guys in the Crimson drum corps get together to practice, rehearse, and get things figured out for a tour? That's gotta be a lot of work for what you guys have to do collectively.

Pat: Yeah! Well, since the very beginning, when Robert suggested three drummers, Gavin [Harrison], Bill [Rieflin], and I were on the phone going, "What are we going to do?" (laughs heartily) "We gotta get together and figure it out!" You know, you can talk about it, but eventually, you gotta be together. So that's what we did.

We sent files back and forth and we rehearsed separately at home, and Gavin made little videos and ideas for how to jigsaw the pieces together. We first met at Gavin's house—just the drummers—and actually, we spent about a week together. We spent the first three days just on "Level Five" [from March 2003's The Power to Believe], and the next two days on "The ConstruKction of Light" [the title track from May 2000's The ConstruKction of Light]—those two songs only, and just the form. It was easy enough for me, because those were kinda my old parts, and they got chopped up and redistributed.

But then we went into the drum pieces, and we went away for a month to work on our parts separately. We did all that process again at a different studio, just the drummers. And then we did it a third time, just the drummers. By the time we met the other musicians in Crimson to play as a band, we three drummers could play the songs top to bottom without any accompaniment. We knew our parts.

Then, we had to watch and wait to react (chuckles), waiting to see if Tony [Levin, Crimson's ace bassist], Robert, and the other guys in the band were going to get off on what we had created—or if we were going to have to change things.

And that's the process we've continued to do, every year. We get together, just the drummers separately, for at least a week. And then just before the band rehearsals, we try to go in a week ahead and do those rehearsals without the band. We set up in a circle and stop and start, and talk to each other. It's like, "Maybe you take that part, and let's try it the other way"—you know, all that stuff without the other guys in the room with us.

Mettler: Pretty cool, I'd say. Now, originally, did you know when Robert suggested the triple drummer lineup that you were going to be literally at the front of the stage? How did that come up?

Pat: I did know that! When Robert called, I think it was September [2013]. I was sitting at my desk, and when my phone lit up with his name, I thought it was because I'd seen him six months or a year before, when he was retired. (laughs) I answered the phone, and I was like, What the f---'s up?" And he says, "Oh, I want to get the band back together." He then says, "I have a new idea—it's three drummers. I see three drummers. And the drummers are at the front of the stage. There's three Americans, five British, and will you do it?" And I said, "Yes!" Then I hung up the phone, realizing I never asked who the other musicians were! (all laugh) It was about a day later that Bill Rieflin called me, and then I understood better what was going on. [Rieflin played drums and keyboards with King Crimson from 2013 through 2020. Whenever he would take the occasional sabbatical, Jeremy Stacey would be there to fill in. Rieflin passed away from cancer at age 59 in March 2020.]

Mettler: Had you ever played in that position on a stage before, or were you always a backline guy?

Pat: Oh, well, I certainly prefer the backline. I've been upfront a few times. but usually, it's a situation where the whole band is upfront. Like when Trey [Gunn, the Chapman Stick innovator who played in King Crimson from 1994 to 2003] and I play as a duo, we set up sideways, right at the edge of the stage. Crimson is different, because the other musicians are behind us. You can imagine, it creates a lot of issues for giving cues. Usually, if you're the drummer, you're in the back, and you see the whole "football field," you know? You can see all the action. But that's not the case now—and I don't want to turn around. I don't want to turn around to look for cues, and distract the audience.

Mettler: How did you figure that out? I mean, that's gotta be a tough, tough thing. Because, like you were saying, you're also hearing things differently on the stage out front as to where the music is coming from, either at you or around you.

Pat: Right. Well, we use in-ear monitors. We have really good ones with Crimson; we have the Roland [personal] mixers. We have a nice situation where things are submixed and sent down different channels, so each of us has a little bit different way to control things. I may not be able to control [saxophonist/flautist] Mel Collins, who may be on one fader for me. Over in his world, he has five faders to separate his instruments, but he might not be able to separate my hi-hat and kick drum; he just has a general mix of Pat. So, we adjust those.

We're really lucky with these in-ear monitors. Being so far apart onstage, it really, really helps. It's more of a visual thing, especially for the drummer in the middle. I'd have to turn around to take a cue, so most of the cues of musical, and the bar links are set—but there are places where they're not, and we have to sort of leapfrog. I can see Robert and pass a cue to Gavin, so he doesn't have to turn around.

We do this thing we call "anchor points." It's a term Gavin uses. We'll make musical anchor points that reconfirm we know where we are! (chuckles) If you can imagine we're all in different time signatures and grooving on down the highway, we'll make a reference in a moment there where you should hear that splash cymbal followed by that badonk—and if you don't hear those two things, you know in about 30 seconds it's going to be a trainwreck, and you better find your way back to the right part in the music.

Mettler: Is there one King Crimson song you think is the most difficult to play?

Pat: With Crimson, it's probably the one you mentioned—"Fracture." And actually, "Larks Four" is also very difficult for the band. It's got enough repetition in it that you think you know where you are, but there have been times onstage with that song where we reach a point, and somebody draws a blank—and the guy who's supposed to introduce the next section doesn't.

We have one we still talk about, within the band. It was in New Jersey. In "The ConstruKction of Light," Tony got out of frame with his part, and nobody could figure out how to get back! If you're familiar with the song, the drums and the bass play the introduction, and then the bass player continues with the guitars. And that's where it happened, where they came in at the wrong place. So, Tony restarted in a different place, and we drummers thought, "Ok, we know what to do. We'll jump in right here." But when we jumped in, they stopped! (laughs heartily)

It was just a series of trainwrecks—and yet, when you listen to it, it sounds pretty good. If you weren't in the band, you might not know it even happened!

- Log in or register to post comments